Bigger on the inside

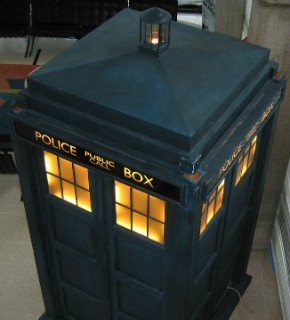

I’ve never seen Doctor Who and don’t plan on beginning now, but I often hear from my students about the Tardis, a space-and-time ship capable of camouflaging itself as an ordinary London police box. The Tardis, I’m told, is “bigger on the inside.”

Whatever the technical marvels of the Tardis may be, places that are bigger on the inside are as common as carrots in folklore and fairy tales. I think of the small cave on an island in Lough Derg, Ireland, where medieval pilgrims could explore the precincts of purgatory, or John Crowley’s magic realist novel Little, Big, in which the geography of fairyland is “infundibular”—an ever-widening series of concentric rings, such that “the further in you go, the bigger it gets.”

If you find this idea as enchanting as I do, perhaps that’s because it tells us something about our ordinary as well as our otherworldly concerns. I’ve never knowingly visited purgatory or fairy land, but I have set foot in a few small places that, once entered, prove to be bigger on the inside. Small libraries, for example: I spent much of my childhood in the 23rd Street branch of the New York Public Library, reading the entire Landmark biography series from Jane Addams to the Wright brothers. Good books open onto great worlds.