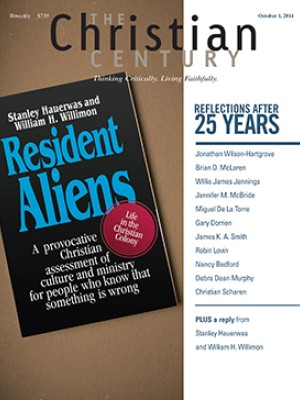

Targeted medicine: Resident Aliens at 25

In 1989, Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon sparked a lively debate about church, ministry, and Christian identity with their book Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony. Twenty-five years later, we asked several pastors and theologians to offer their perspective on the book and its impact. (Read all responses.)

When I read Resident Aliens I thought about blood pressure. Not because the book raised mine, but because an analogy to blood pressure medicine describes my reaction to the book. The medicine that saves patients with high blood pressure will harm those with low blood pressure, and vice versa.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I think the primary patients of Resident Aliens were traditional mainline Protestants—epitomized by Methodists, who largely understood themselves to represent America’s religion. Jesus had value for the afterlife, to be sure, but he also had value in strengthening the American people for their role as global leaders in this “Christian century.”

The authors’ bold counterclaim was that Jesus did not come to be the mascot, watchdog, or spiritual cheerleader for the American project of pursuing happiness. The church was more than “yet another ‘helping institution’ to gratify their individual desires.”

With this, of course, I agreed and still agree. But around 1990 I became concerned because I saw the religious right gaining steam and its members didn’t read Hauerwas or Willimon. I worried that if moderate and progressive Christians retreated into their churches as resident aliens, focusing on “being the church” rather than “transforming the world,” the religious right would be the only Christian voice in the public square. That would be bad, I felt, for Christian faith and for the public square.

That is largely what has happened over the last 25 years. Now, perhaps ironically, the religious right has so deeply fused its agenda with that of American nationalism (also known as “exceptionalism”) that it is in a situation very similar to that of the mainline Protestants for whom Resident Aliens was originally prescribed. Its members feel that America is rightfully theirs, a possession to “take back” or defend or transform. They elect politicians, set (or obstruct) policy, and define Christian for more and more people.

Hauerwas and Willimon saw this coming. The fundamental issue, they said, was “not whether we shall be conservative or liberal, left or right, but whether we shall be faithful to the church’s peculiar vision of what it means to love and act as disciples.” Of course, describing that “peculiar vision” is not as easy as it sounds.

The Bible contains many images that convey a wide range of possible relationships between “church/people of God” and “society/world.” Resident alien is one of them, and it is an important corrective medicine to chaplaincy to empire, helping institution, or conquering army.

But medicines are only of value in relation to the disease of the patient, and alien colony (a problematic image in itself) isn’t the only image we need. Yeast, salt, doctor, and light, for example, are alternative images that suggest a concern for “transforming the world”—while also requiring a unique, countercultural identity. Perhaps the book that needs to be written now might be Resident Salt, Light, and Yeast . . . or perhaps Doctor in Residence?