Kenosis and Christendom: Resident Aliens at 25

Like Willimon and Hauerwas, Donald MacKinnon began with Philippians 2.

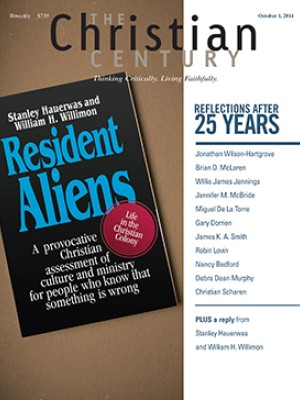

In 1989, Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon sparked a lively debate about church, ministry, and Christian identity with their book Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony. Twenty-five years later, we asked several pastors and theologians to offer their perspective on the book and its impact. (Read all responses.)

Resident Aliens begins by quoting the well-known Christ hymn in Philippians 2, and it draws on the Philippians 3 notion of our commonwealth being in heaven. The authors develop the idea of the church as made up of resident aliens in this world, because our true home is not in the world. They say this assertion is needed because we now live in a post-Constantinian moment, with the church no longer supported by the official powers of society. At the center of the Christ hymn is a claim about the core of God’s work in the life, death, and resurrection of the rabbi of Nazareth: Jesus’ self-emptying, or kenosis, in and for the sake of the world.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But ironically, the rhetoric and substance of Resident Aliens continually turns on an embattled consolidation of identity and action over against the world. For instance, Hauerwas and Willimon write, “In fact, we are not called to help people. We’re called to follow Jesus.”

At a time when many formerly established evangelical and liberal Protestant denominations found themselves losing their cultural establishment, the book argued for a new identity for Christians as a distinctive minority, despite Christians remaining the overwhelming majority in the United States. This mode effectively makes a virtue of a necessity—seeming to choose disestablishment when in fact it has come down upon us like a judgment.

Twenty years before Resident Aliens, theologian Donald MacKinnon named disestablishment as judgment in a lecture titled “Kenosis and Establishment.” Like Willimon and Hauerwas, MacKinnon begins with Philippians 2, speaking of the “costliness of the incarnate life.” But his argument does not underwrite a Christian withdrawal, consolidating identity over against the world, à la Resident Aliens. Rather, he argues for accepting dispossession in and for the world. “To live as a Christian in the world today is necessarily to live an exposed life; it is to be stripped of the kind of security that tradition, whether ecclesiological or institutional, easily bestows.” His argument resolutely outlines the losses and difficulties of such a life.

MacKinnon does not predict the form of the church stripped of its former status. Yet he ventures that our frailty will offer a means of presence rather than withdrawal. MacKinnon notes that in welcoming this new frailty we will find that “it is in our weakness that our strength is made perfect.”

I offer a contemporary example: Augsburg College, which is located in a downtown Minneapolis neighborhood inhabited by a large population of newly arrived Somali Muslims. Augsburg has declared that it is a college “called to serve our neighbor.” The school’s nation-leading program of community service has created neighborhood friendships across faith traditions, and it has encouraged a growing number of Somalis to enroll and consider Augsburg their school too.

The church today is learning that its deepest faithfulness is not in withdrawal from the world but in an anarchic giving itself away in and for the sake of the world.