Sunday, August 24, 2014: Romans 12:1-8

In 1988, Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. It is a narrative account of a former slave’s memories of post–Civil War Ohio. The story includes a “dean” of preachers—“Baby Suggs, holy”—who delivers an unforgettable sermon to those listening in a clearing in the woods.

In this sermon, Baby Suggs urges the hearers to love their flesh, because “out yonder” other people do not love it. But she does more than this. She also uses her body, particularly her twisted hip, as the climax of her heartfelt sermon, while the community brings it to a close with music.

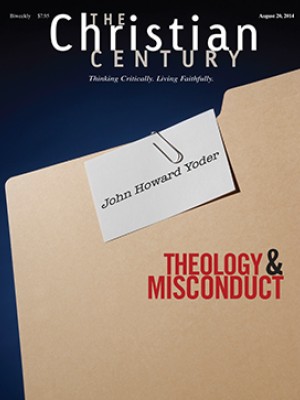

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Baby Suggs talks about the body and uses her own body to preach a word of hope and life to those in dire need of love. It’s a timely word; the people’s black bodies have been mistreated and deemed ugly and worthless. Baby Suggs’s explicit exhortation to love the flesh—that is, to love the body; it is not the Pauline idea of “flesh” she has in mind—suggests the important role of the human body in life in general and the religious life in particular.

The apostle Paul seems to suggest the same to the church at Rome. He appeals to these Christians, in light of the “mercies of God” he has just written about, to “present your bodies as a living sacrifice.” Bodies matter for Paul (see also Rom. 6:6, 6:12, and 8:23). And they matter for Christian discipleship. Paul foregrounds the human body as critical for the Christian response to God’s mercy.

Historically, of course, Christians have often appeared to be apathetic toward the body and its significance in the Christian life, or they have viewed it as antispiritual. At times, Christians have taught that one should escape the body or “material things” in order to grow spiritually. This perspective suffers from theological amnesia when it comes to the incarnation of God in the human body of Jesus Christ. In Christ, God embraces the body and implicitly affirms human bodies as significant for the spiritual life.

When the body is deemed unimportant, anyone can be treated in any way. Such treatment, after all, is believed to be disconnected from the spiritual life. This results in brutal slavery, the context of Beloved. It results as well in the exploitation of women’s bodies and the sex trafficking of children’s bodies. An antibody perspective will lead to inhumane actions against other humans—even in the church. Little bodies are the most vulnerable, as we’ve seen in the track record of sexual abuse in the church.

Inhumane, antibody actions imply an antihuman mind-set. But to be human is to have a body, and a body is part of Christian spirituality. To be Christian, as Paul implies, is to have a body and to be a part of a body.

For Paul, a bodily sacrifice is “holy and acceptable,” but it is also “spiritual worship.” Materiality is vital to spirituality. Followers of Jesus are embodied, corporeally and corporately. One’s body, one’s whole self, is offered to God, which means this sacrifice is not just a mental exercise. It involves the entire body of a community. A “living sacrifice” is a sacrifice that is embodied daily. It is not dead but alive, and it manifests through everyday behavior. Just as one’s body travels from place to place, one’s spiritual worship is not limited to a specific domain but travels as well.

Paul’s ancient metaphor of body is also a social metaphor: it implies unity among diversity (see also 1 Cor. 12:4–31). So it should not be surprising that the living sacrificial bodies are acceptable and good as they remember “the one body in Christ.” One sacrifices the individual body for the corporate body: one should not “think of yourself more highly than you ought to think,” because in this body there are “many members, and not all the members have the same function.”

Yet everyone in this community has gifts, and everyone has received grace from God. The gifts are different, but they are all vital to the wholeness of the one body. Individual bodies are different as well but ultimately form “one body.” Furthermore, Paul teaches that the individuals “are members one of another.” To make a corporate body of Christ, one needs the individual bodies to sacrifice for the larger whole.

This is an indication of transformation—and of a lack of conformity to the world’s norm. The one holy, living body implies that people are interconnected, forming a mutual web of loving sacrifice. There is an ethical thrust embedded in this notion.

But here, Paul insists that in the Christian life, bodies matter. Everybody is a somebody, because in the kingdom of Christ there are no nobodies. Every body matters because the body of Christ matters. No body should be excluded.

During the civil rights movement, African-American men enduring racism lifted signs that read “I Am a Man.” They did this to assert their humanity and to help others recognize that their black bodies mattered. This was an attempt to represent a renewed mind in the one body, and a renewed embrace of any body—a body whose ultimate end is redemption (Rom. 8:23) and resurrection (1 Cor. 15).

There is no room for a disembodied faith, because humanity’s future has a body. We can’t escape it, and neither Paul nor Baby Suggs would want us to—because it is holy.