The ultimate mystery

Russia’s recent incursion into Crimea has brought back memories of the cold war. George F. Kennan, a scholar, historian, and State Department adviser, is known as the father of America’s “containment policy,” which was based on his conviction that the Soviet Union was expansionistic and that world peace depended on the United States and its allies containing Soviet territorial ambitions.

Kennan later became an eloquent critic of a U.S. foreign policy that favored dialogue with the Soviets. In perspective, some of his ideas and suggestions have been helpful, some not. I loved his 1993 book, Around the Cragged Hill: A Personal and Political Philosophy.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In a recent issue of the New York Times (February 23), journalist Fareed Zakaria reviewed The Kennan Diaries, a collection of Kennan’s essays, letters, and meanderings. I was surprised when Zakaria said: “Kennan’s views were rooted in history, philosophy, and—somewhat surprising to me—faith.” On Good Friday, 1980, Kennan wrote in his diary:

Most human events yield to the erosion of time. The greatest, most amazing exception to this generalization . . . A man, a Jew, some sort of dissident religious prophet, was crucified. . . . In the teachings of this man were two things: first, the principle of charity of love . . . secondly, the possibility of redemption in the face of self-knowledge and penitence. . . . The combination of these two things . . . shaped and disciplined the minds and values of many generations—placed, in short, its creative stamp on one of the greatest flowerings of the human spirit.

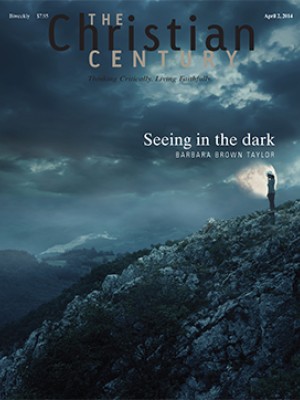

This season I’ve adopted a new discipline—a Lenten pilgrimage, albeit a brief one. I walk across the street from the Century office to the Art Institute of Chicago, climb the stairs to the second floor, and spend an hour or so in the Middle Ages and Renaissance galleries. Many of the paintings are of the crucifixion. In every age, including our own, this event has compelled artists and musicians with its raw human drama as well as its deeper meanings: innocent suffering, redemption, forgiveness, and hope. The result is some of the most sublime art and music ever created.

The crucifixion has challenged Christianity’s best thinkers, who created various atonement theologies. I’ve been thinking about this unlikely claim all my life: that this brutal event has ultimate transcendent significance, that God is in it. I have found myself moving away from the notion that God intended, planned, and choreographed the crucifixion and away from the related idea that Jesus had to die a sacrificial lamb to satisfy an offended and angry deity.

My thinking has been shaped by years of listening to and praying with people who are suffering and by my own experience. I believe that parenting tells us much about God. As parents we give our children the freedom to risk tragedy and, when they suffer, we do everything we can to take on that suffering ourselves. Other relationships teach us the same truths. As C. S. Lewis said, to love anyone is to open oneself to heartbreak.

The most radical thing anyone ever said about the ultimate mystery is this: God loves us so much as to be with us in our suffering, to take into God’s own self our most profound experience, to be at one with us.