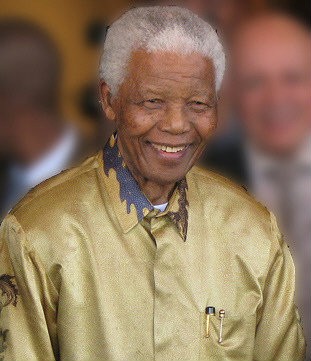

The Nelson Mandela I knew and loved

I met Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela 50 years ago this year in his jail cell on Robben Island. I was a newly ordained part-time chaplain to the prison there. He was with other Rivonia Trialists, who were named for the farm in Rivonia, outside Johannesburg, where they had been arrested on July 11, 1963. Mandela was not with them in Rivonia; he was already serving a five-year sentence for leaving the country illegally, and was tried with the Rivonia Trialists because documents incriminating him were found at the farm.

The Trialists had been flown secretly to Robben Island after being sentenced to imprisonment for the rest of their natural lives for the crime of “sabotage.” The guards were very edgy about their new prisoners, and determined to show these “terrorists” how tough they were. Sunday, when I visited, was their one day off, but it was spent in total lockdown. I was not allowed to gather them for a normal service of worship, but had to walk up and down the hallway between their cells, trying to make eye contact with each occupant as I passed. All but one member of the small group had experienced mission-school education, and they were at home with Christian worship. Preaching under these circumstances was tough, but I tried to leave each one with a word of encouragement.

Their singing, however, couldn’t be bound by iron bars—and the great hymns of the church, well-known to them, echoed powerfully through the hallways, their melodies often taken up by prisoners in other cell blocks. My memories of Nelson Mandela were of a strong, vital person in the prime of his manhood, all strength and contained energy. He had a ready smile and clearly appreciated the dilemma of a young minister trying, under the cold eyes of the guards, to bring a moment of humanity into this desolate place. Only once, on a very cold day, was I able to persuade a guard to let the group out into the prison yard, where we gathered in a sunny spot. That day I changed my text to, “If the Son sets you free, you are free indeed,” letting them choose how to spell Son/sun. They enjoyed the joke. The guards did not.