The absurd in worship

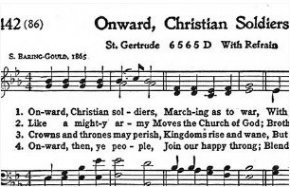

The publishing house of my denomination, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), will soon issue a promising new hymnal. Naturally the hymns had to pass theological muster, but the range of styles and themes in this collection is wide—newer hymns, global music, praise songs, spirituals, Taizé melodies and rousing old favorites. And once again, for the third hymnal in a row, Presbyterians will not find “Onward Christian Soldiers” in the mix.

Good riddance. This hymn, with its “hut-two-three-four” tune and its warring call for Christians to raise the battle flag, has long outlived its usefulness. Recently, one of my friends threatened to resign her role as church school assistant because the lead teacher insisted on having the children sing, “Christ the royal Master, leads against the foe. Forward into battle, see his banners go!” I stand with my friend.

Years ago, when the hymn was first excised from our repertoire, there was controversy over it, but that has mostly disappeared. In a world grown weary of religious strife, a world where the word crusade arouses more anger and embarrassment than resolve, few are nostalgic for a hymn that celebrates Christian soldiers marching to war.