Sunday, September 12, 2010: Jeremiah 4:11-12, 22-28; 1 Timothy 1:12-17; Luke 15:1-10

A few years ago when Tomas wrecked a car, the police didn't care about his immigration status. But times have changed. During a routine traffic stop a few days ago, Tomas was handed over to the INS. Now police have taken him away. His wife and friends are trying to raise money to send him back to Mexico so that he can begin the process of arranging his return. Otherwise he'll be deported to Mexico, and it will be five years before he can come back to the United States.

Until recently a kind of balance existed in this country. Many U.S. residents understood that the alien labor force was keeping food prices low and supporting public affluence. That realization offset anxiety about the legality of the aliens' status. But as economic times become more difficult, more and more people have begun to feel that they are receiving no benefit from the wealth created by such workers. Undocumented immigrants have become the target of their resentment.

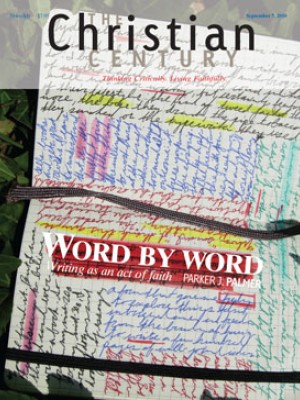

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The economic crisis resulted in part from a deliberate loosening of controls. The U.S. allowed borders to be breached in areas located between U.S. financial institutions and their enterprises. Safeguards left over from post-Depression reforms were abandoned when business owners said they were slowing business. Removing these barriers was supposed to stimulate commerce and create wealth—and it did for some, for a while. But now aliens are being deported, and executives are being prosecuted. Things have gotten out of balance, and somebody has to pay.

Nobody expects the new measures to solve all of the problems, but the crackdowns satisfy a human instinct that requires a restoration or perceived restoration of balance. As long as the injustices are offset by enough advantages, we tend to support the status quo, convincing ourselves that justice is being served as well as it can be. But when wrongs seem to be occurring in excess, we notice them, and we cry out for justice.

However badly we humans express this desire for justice, we get that desire honestly—from God. It is our taste of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil that has separated us from other creatures. In Genesis, God hears the appeal for retribution from Abel's blood in the ground, and God has to mark Cain to make him vengeance-proof. God's will to save is countering God's will for judgment.

We've inherited this double purpose. We want our need for justice satisfied, and we want mercy available. No law can resolve this neatly. The complexity of courts and judges mirrors the complexity of circumstance and character, and unfairness in the legal system corresponds to the intrinsic conflict between the righteousness of just desserts and the rightness of forgiveness.

In the scriptures for September 12, the wrong in the world is addressed either by retribution or rescue. It's not addressed by some goddess with a blindfold. It's not decided by weighing all evidence to the finest detail on a balance. Instead, the Bible's balance offsets punishments with pardons and finds a middle way between being merciless and condoning. God reacts in righteous wrath—and the scales are made level by punishment or restoration. The passion of offended righteousness is offset by the passion of profound love—love for perpetrators as well as for victims.

Paul proclaims the undeserved grace of God and justifies God's goodness. He declares that God's having forgiven him is exemplary, that it is meant to encourage other sinners to hope. His is a story of redemption, the biblical story of guilt covered by God's decision to restore.

Jeremiah's contemporaries see the same looming doom that he sees and can't muster trust that faith in God will do any good. Their apprehensions drive them further into unholy alliances. God's disgust is deep, and their destruction will be correspondingly thorough. Retribution is all—but not quite all. God will leave a little of his heritage alive, to start over, as with Noah and his household.

Failure to keep faith with God also convicts the mutinous multitude led from Egypt by Moses. When Moses vanishes to speak with God, the people reach for idols. Their effort is wrong—fickle, foolish, ungrateful and ungodly—and God means to wipe the slate clean, to give up the Exodus project. But like Abraham before him, Moses speaks up for clemency and God relents.

Part of the reason that the world is out of kilter is that it's unable to find God. Jesus' religious contemporaries tried too: they tried to locate God by establishing where God can't be. God can't be on the wrong side of rules about holiness. Jesus' insistence on companionship with sinners suggests to them that he's not the person of God he claims.

Jesus doesn't suggest that holiness doesn't matter. He finds a different way to establish the right relationship between wrong and right. The repentance of a sinner so delights heaven that it justifies all the risk holiness takes in lowering itself into the midst of the fallen. Jesus reveals the God for whom that balance-striking makes sense—God becoming man that man might become God.

In Jesus' actions and in his story, we find the elusive God to whom Moses' liberated captives can't be faithful, the God whom Jeremiah's contemporaries betray.

The keeper of the sheep knows when even one of a hundred is missing. That sheep has so much value that the shepherd will work past all expectation until the lost one is restored to security, relationship and rest. The balance will be restored not by finding someone to punish for things having gone wrong, but by rescue.