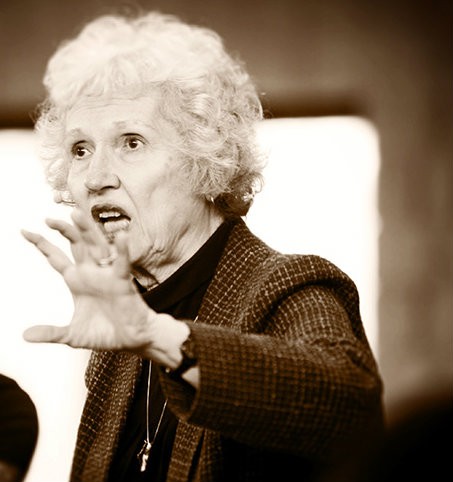

Literary agent: A profile of Phyllis Tickle

In 1987 Phyllis Tickle, then the religion editor at Publisher’s Weekly, foresaw a rising demand for religious books. Books, she wrote, were about to become “portable pastors.” Her prediction proved true. Beginning in the early 1990s, sales of religious books began a steady increase. In fiscal 1997, when Tyndale’s Left Behind series hit bookstores, growth in the market surged again (especially for Tyndale) and has remained robust.

The market for religious books continues to expand. Lynn Garrett, who took over Tickle’s post at PW when Tickle retired in 1996, said recently that despite predictions of a decline in religion sales in 2003, the Association of American Publishers was seeing an increase. “The latest figures we published (February 9) showed a 36.6 percent gain in December over the previous December.”

Tickle has been in the middle of the religious publishing explosion. “Phyllis revolutionized the religious coverage in PW,” said Garrett. And coverage in PW reverberated in the bookstores. Garrett adds that even today, in a less demanding role as a contributing editor at PW, Tickle continues “to play a key role in our religious coverage—a consultative role, in putting together the editorial calendar and alerting us to trends.”

In addition to her “midwifing of book ideas” at PW (the term is from Books & Culture editor John Wilson), Tickle has produced many books of her own. She is also a frequent speaker on spirituality and has earned the May’s Award for lifetime achievement in writing and publishing.

Tickle has perceived strong spiritual appetites in the culture, and her platform in the publishing world has allowed her to respond to them. She has also rallied a devoted readership for her own books, especially for her popular three-part series called The Divine Hours.

The first volume of this literary and liturgical reworking of the sixth-century Benedictine Rule of fixed-hour prayer, Prayers for Summertime, sold out its first print run in a month and reached number 200 on Amazon.com on the second day it was offered. (It was followed by Prayers for Autumn and Wintertime and Prayers for Springtime. The series has sold approximately 50,000 copies.) The books, made up of selected readings from the psalms, Gospels and other sources, are neither didactic, narrative nor “how to,” and could be called repetitious. But they have tapped into a spiritual yearning that reaches across denominational allegiances.

The series has had special appeal for people who come from what Tickle calls “liturgically challenged” churches. Once Tickle got over her aversion to signing The Divine Hours (“On what authority would you sign a prayer book?”), she noticed that she was encountering people, mostly women and many of them young, who find liturgical traditions new and exciting.

Tickle’s brand of spirituality is intuitive and liturgical. Sacred readings in the context of simple faith is her poetry, which, in part, is why she wrote The Divine Hours. The prayer offices as fashioned in the series include a morning and a midday office, and vespers (early evening). (Compline—an optional office to be done before sleep—has its own section.)

She has kept the hours for almost 40 years, though she is shy about saying so. Behind this practice lies a manifold commitment to exercising praise as the work of God: it embraces the concept of a cascade of prayer being lifted ceaselessly by Christians worldwide; recognizes every observant as a part of the communion of saints across time and space; upholds the centrality of the psalms as the informing text of all the offices (since Jesus used the psalms for his devotions); keeps fixed components, such as the Lord’s Prayer; and sees the repetition of prayers, creeds and sacred texts as integral to spiritual growth.

Tickle says that The Hours appeals to people because “we are post-Enlightenment, living in a kind of neo- medievalism. . . . The last time we believed in the mysterium—things we cannot see and what we cannot hear—was in the medieval times.”

“Her sense of timing was perfect,” says Wilson, who himself uses The Hours for devotional reading. “Many Christians who grew up in traditions in which set prayers were alien have a spiritual home in these volumes.”

After The Hours came out, Doubleday approached Tickle about writing a memoir. That idea, she says, sent her into a “six-month tailspin.” “I couldn’t for the life of me figure out what I’d ever done that was worth reading about. My life as cocktail party conversation? Yes. To sit down and read about it? I don’t think so.”

Doubleday prevailed. The result was The Shaping of a Life (2001), which examines her first 30 years (“the shaping phase,” as she calls it). The sequel, The Sharing of a Life, is due out in 2005.

Tickle lives on a farm in Lucy, Tennessee, 20 miles north of Memphis and at one time separated from the city “by at least a hundred years,” as she writes in her book Wisdom in Waiting (Loyola), also just out. Lucy is part of a bucolic landscape of dry grasses and low-growing cotton, oaks and elms and flowering hollyhocks not far from the Loosahatchy River. A country church near Freddie May’s Restaurant displays a marquee that reads, “The Way of the Lord Is Upright.”

Tickle, a loyal Episcopalian, is married to Sam Tickle, a retired pulmonary specialist and second-career carpenter. She is the mother of six living children (one is deceased) and is also a grandmother and great-grandmother.

As we talked at her dining room table, morning light fell over moss on rocks in a terrarium by the window. Gay Bob the cat (as she calls him) skulked about. Gay Bob (“the second gay cat we’ve had”), she says, “convinced me homosexuality is in the genes.”

She grew up “androgynously, as both the son and the daughter,” in Johnson City, Tennessee. Her father was a college professor who wanted his daughter to follow him into the academy.

“I was fairly sheltered as a child, Tickle says. “My father being an academic meant we didn’t live what one would call a bad-mannered life. We were Presbyterian, very conservative. I remember that when Rita Hayworth and Ingrid Bergman had their extramarital affairs and illegitimate children, I wasn’t permitted to see the movies they’d made lest I become contaminated by some sort of celluloid contact.” Tickle reveled in her father’s affections and “learned to follow the sound of applause.” But her father warned her, “If you start believing your press releases you’re in real trouble—it is much easier to live for human applause than for divine approval.”

Her relationship with her mother was less endearing. After Tickle was born her mother became deathly ill and remained hospitalized for three months, and her father assumed the sole parenting role. Her mother later confessed to her daughter, “ I was afraid to love to you because I feared I’d have to leave you, or that you would die while I was sick.” Tickle recalls, “There was not room in her life for anything other than my father. This is not to deflect guilt or blame on my family. I’ve made my peace.”

In 1955 she married Sam, whom she’d known since their days in the nursery of First Presbyterian in Johnson City. Soon after her marriage she experienced a defining spiritual moment. She was teaching high school Latin and English in the Memphis area while Sam attended medical school. One day she fainted while standing beside him in a grocery check-out line. Sam got her safely home and to bed, where she began to feel abdominal cramping and realized she was having a miscarriage. Her doctor administered a new drug to stay the cramping. Before she knew what had hit her, Tickle says, “I woke up to the funniest thing . . . the most bizarre thing . . . the most confusing thing . . . somewhere over there Sam was screaming.”

The drug was soon to be taken off the market because it had caused several deaths. She describes her near-death experience in The Shaping of a Life:

I was up in the corner of the room just above my bed. That is, was in the space where the outside wall and one of the inside walls of the room converged with one another and the ceiling. . . . My back was curved and my legs were drawn up in front of me and my chin was resting on my fists. . . . I felt exactly like a gargoyle snugly fashioned up under the overhang of a cathedral roof. . . .

Something had caused me to look to my right; and there in that spot where there should have been only more ceiling, there was only light. . . .

I thought to myself it was like a glowing culvert between two meadows. . . .

A near-death experience “irrevocably changes you. There is no way to un-do” the experience, she says. “By the time you come back it is too real and too integrated into every fiber of your belief system. The end result is you simply aren’t afraid anymore. . . . The experience clearly said to me, ‘This is what it is like. This is what you’re getting ready for. This is the homecoming.’ It’s like knowing the last chapter of a really good book and being able to read your way through it without the tension of wondering how it will end.”

“Who knows?” she says. “Maybe it is the physiological process by which the spirit leaves the body or is translated into the resurrection body. I have no problem saying there’s no contradiction between science and my experience.

“The notion that perhaps, just for a moment, I slipped out of this level of consciousness and got a waft of that one is very exciting. It is a glimpse of the resurrection body: the seed planted and coming back as the full ear of corn next spring. I love the notion that my body is going to live forever in the same way seeds live forever, though they die. Especially in the Christian experience, [we understand] that Jesus chose to die that way for a reason, and that he leaves me the opportunity to choose little places I will die each day.”

When Sam finished medical school they moved to Pelzer, South Carolina, where he and a classmate opened a small hospital. At the time, Pelzer had the highest murder rate in the country. Tickle describes a call she received one night from the wife of the police chief: “They’s been a shootout up front of the roadhouse on the highway. They’s left two of ’em dead in the street. We can’t move ’em without Doc or the coroner, and the coroner’s drunk. Tell Doc to come on up quick as he can.” (One of the bodies was blocking traffic.)

“I had never seen raw human emotion the way I confronted it the years in Pelzer. It was where my soul first began to become Christian,” she says. She helped with the business side of the hospital work and remembers taking Xs as signatures on payments. Sam, in the meantime, realized he had to go beyond medical terms to explain to his patients how they should understand and treat their conditions. “He wouldn’t say, ‘Now take this five times a day.’ He’d say, ‘Now what this is, you see, this is a little solution of stuff that’s got other stuff in it that’s gonna kill the bugs that are in you, like putting Drano in your drain.’”

The people in Pelzer were not motivated by “cultural pride or professional ambition,” says Tickle. At the same time, they were fiercely loyal to one another. “Someone could get drunk and then ‘drop’ someone else in the street. Then the guy who’d ‘dropped’ the other would be back taking care of his wife or his kids. It was a morality driven by emotional faithfulness,” she says.

“They shattered my categories, just cracked ’em wide open,” she says. “Their devotion to God and the Christian way was uninformed by questions of canon and historicity.” This experience, too, shaped Tickle’s faith.

“There is a stage in which myth is the truth” (as in Pelzer) and a stage in which truth is “seen as myth” (echoes of her intellectual upbringing), “and then it comes back to being the truth, only then we call it poetry.” The people in Pelzer helped her discover the poetry of faith.

“For the first time in my life I understood the kind of people whom our Lord moved among, addressed and co-habited with. They were real. Up to that point I’d assumed he spent his time with refined people like me, in houses like mine, and with manners and intellectual override. It was an epiphany to understand that life in Pelzer was the kind of life lived by a Galilean peasant.”

Prior to joining PW in 1992 as its first religion editor, Tickle worked for nearly two decades at St. Luke’s Press, which was begun in the mid-1970s at the Memphis College of Art, where she was academic dean. She and others started the press because they had perceived literary talent in their students but knew of no outlet for their work. When this small publishing house faced extinction Tickle bought it, using money from her deceased father’s estate. She took St. Luke’s and other small imprints to a level of excellence that attracted the attention of Peachtree Publishers, which bought it in 1987, and which, two years later, was in turn bought out by the Wimmer Companies.

Tickle completed her three-year contract with the firm and then retired from publishing to write. Then PW called. Daisy Maryles along with with the late Robin Mays had a vision for expanding religion coverage at PW. Tickle’s experience as a publisher, writer, instructor and public speaker, as well as her personal devotion, made her the perfect candidate to launch PW’s religion section in 1992.

Because she has been numbered among the gatekeepers of the religious book market, she’s found more and more people from the mainstream and religious spheres turning to her as an authoritative commentator on religion.

“In an earlier culture, I would think of Phyllis Tickle as an imaginative, benign ‘mother superior’ to women and men who are finding a voice in devotional literature,” says church historian Martin Marty. Today, he says, “Christians are listening less to formal philosophically attuned systematic theologians than to spiritual writers who use narrative and devotional forms,” as Tickle does. “In a time when much ‘spirituality’ writing is of an air-heady sort,” he says, “hers is heady, and yet anchored in the great traditions.”

“Most Christians are really afraid of pietism, and the last thing I needed was the sense I was being pious. Religiosity gives me a stomachache,” says Tickle. “We all have flaws and faults, and all the discipline in the world isn’t going to get rid of them. That’s why we have spiritual disciplines. These things teach us.”

She rises at 6:00 A.M. for the office of prime. She drinks Postum and offers petitions and intercessions (if it’s cold she does her praying in bed). Next she writes for four hours and rides a stationary bike (for her “funky back”); then she reads the midday office and gives her afternoons to work for PW. Vespers and compline follow in due course. Then it’s back to bed.

Tickle says she still has “zillions” of questions about faith and about God. “But they don’t keep me up nights. Part of the wonder of being 70 is that you’ve gotten to a place where questions are almost like trophies on a shelf, safaris I’ve made. It all becomes so much simpler,” she says.

But “just because they’re trophies on a shelf doesn’t mean they aren’t questions. It just means I’ve parked them.” Tickle adds, “I believe in the literal truth of the Bible. You just have to let me define what I mean by that expression.” She said to a young rabbi once, “You know I believe in the virgin birth because it’s so incredibly beautiful. How could it be otherwise? As for the mechanism about how it happened, who cares? It’s the beauty that persuades me.”

She wonders whether she had the near-death experience “because I am a spiritual weakling. If you know where you’re going and are sure of it, it’s easier to steady yourself than if you had [the assurance] only in the abstract.” She adds, “It’s reassuring, almost pleasant, to know I don’t have to understand. There comes that peaceful place where I can smile and say, ‘I don’t know and it’s OK I don’t know and it will be OK someday that you don’t know too.’”

Aging baby boomers account for the largest chunk of book buyers, says PW’s Lynn Garrett, because they are reaching the age when people confront “life’s ultimate questions.” As has been the case throughout their generational curve, what baby boomers hanker for, the market provides. In this case it has been religious books with a mystical aspect. They also are interested in liturgy, regardless of denominational affiliation or lack of religious background.

Garrett says that George Gallup predicts sales of religious books will begin to peter out sometime around 2008. But, she says, “ultimate questions don’t go away.” She believes religious books will always sell. In any case, the religion section in bookstores is no longer tucked in the “dark ill-lit back left-hand corner of the store with no signage,” as Tickle puts it. Religious reading is front and center, which, Garrett notes, has made “even cynical New Yorkers sit up and take notice.”

Tickle takes a measured view of all this. “A hot market requires a golden heart and black hands,” she says. “If the heart gets black because the hands want gold, and book publishers publish only for money without a sense of deep responsibility to the things of God, it is a sin before God and a danger to the rest of us. Those who do religious publishing must do so with introspection, respect and humility.” She says that the community of publishers she’s acquainted with—at places like Doubleday, HarperSanFrancisco, Bethany and Baker, to name a few she cited—”is one of the most powerful prayer meetings going on.”

Tickle says that the public’s appetite for spiritual formation and prayer has awakened an interest in keeping the Sabbath, lectio divina and fasting. Among the topics needing to be addressed, she says, is the nature of consciousness.

Before I left her home Tickle took me to her writing space, her bedroom. Her portable wrap-around desktop was made by Sam. She pointed to the hardwood floor and said, “This is where I write.” She drops down a pillow and sits, back against the bed, with the portable desktop on her lap. On the door is a wall hanging that reads, “Make a Joyful Noise. Oompah. Oompah.” That oompah, oompah is Tickle’s gift to the reading world.