Resurrection: “In the midst of death we are surrounded by life!”

Eostre, the Teutonic goddess of fertility with an Anglo-Saxon name, never did much for us except, perhaps, give her name to Easter. Venerated in spring, she evidently had to yield place when Christians superimposed their festive day on hers. And since a rabbit was her symbol, she may have inspired the Easter bunny. So, Eostre, thanks for small favors. For larger favors, however, one must turn to other ideas and names—to the festival some Christians call Pascha, but most speak of as the Festival of the Resurrection.

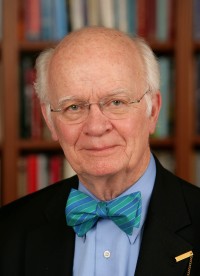

Resurrection season, for us, is a better time than All Saints Day to commemorate those who died during the year. You have your list, and we have ours, of people who have left us this year to whom we attach the word “favorite.” I have written of some of these in this column: our favorite senator, Paul Simon; our favorite Christian lay leader, Al Ward; our favorite seminary president, John Tietjen; add to that our favorite inner city church leader, Dick Sering. When you reach the upper 70s, as I have, you more and more find yourself communicating with families of contemporaries who are keeping a vigil, tending with care and living with hope for an ailing loved one—and with the tended to, who witness.

Little signals and symbols of resurrection hope become more and more important. As I enter my home study, I confront a Niebuhrian-Lutheran statement of realism about the human condition. It is voiced by Pogo: “We have faults we have hardly used yet.” Near it is Habakkuk’s “For the vision still has its time, presses on to fulfillment, and will not disappoint; if it delays, wait for it, it will surely come, it will not be late.” On the door itself is a saying of Martin Luther, sent on the memorial card for Luther scholar Heiko Oberman, who ended his book on Luther with it and reflected on it at the end of his life.

Oberman’s book often gets matched with Richard Marius’s Martin Luther: The Christian Between God and Death, published a decade later. An emeritus Harvard English professor, Marius combined superb style with a drastic thesis: Luther was death-obsessed.

Thanks to e-mail, I could correspond with Marius with some frequency almost to the end of his life. He made no secret of his view that Luther’s Reformation was a tragedy for Western civilization, and that it reflected Luther’s own struggle with the forces of sin, the devil and death. I do not understand the mystery of faith, or why Marius kept it at a distance. I believe he slighted Luther’s lifelong witness to the new life in Christ, which Luther often connected with baptism: the believer is “born again” daily to resurrected life. I reread thousands of pages of Luther during the past three years, while writing my own Martin Luther. That reading turns up frequent evidence of vision, of hope, of “the gift of God [as] eternal life.”

Here is the Luther gem quoted by Oberman—the passage on my study door (recall that for Luther, in this kind of case, “the Law” represented the judgment of God; “the Gospel,” the promise of God): “If you listen to the Law, it will tell you: ‘In the midst of life we are surrounded by death,” as we have sung for ages. But the Gospel and our faith have changed this song and now we sing: ‘In the midst of death we are surrounded by life!’ Media morte in vita sumus.”