William Guthrie’s weird Christianity

The rector of St. Mark’s in-the-Bowery brought the church into relationship with the Greenwich Village avant-garde of the 1920s.

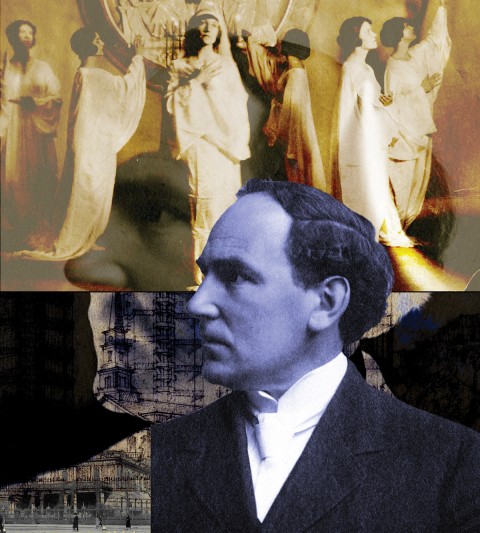

William Norman Guthrie (Century illustration / Source images: Public domain)

John Stuart Mill declared that the crotchet of one generation becomes the truth of the next and the truism of the one after that. Over time, weirdness becomes normalized. Illustrating this point is the career of the distinctly crotchety Episcopal priest William Guthrie, who in the 1920s regularly provided the newspapers with shocking stories of bizarre religious practices perceived as flagrant violations of the most basic tenets of faith and decency. A century later, Guthrie looks like a groundbreaking innovator, even a prophetic figure.

William Norman Guthrie (1868–1944) was born in Scotland to American parents and educated in the US. In 1911 he became rector of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery in New York, holding the position until 1937. His exact religious beliefs were unclear. On occasion, he seemed to deny the literal existence of God, and he described the Book of Common Prayer as a “beautiful museum piece,” declaring himself a “Catholic Futurist, not tied to any age.” He saw little hope for his own mainline tradition, when educated elites had so completely defected from the churches: as he warned, “not only are the Protestants doomed, but they are losing at the top.” When he took over at St. Mark’s, his congregation consisted of just 18 older women.

To counteract this decline, Guthrie sought massively to expand the church’s cultural awareness and sensitivity. He formed close connections with Greenwich Village’s avant-garde artists and thinkers, which also meant being in dialogue with the esoteric ideas then so thoroughly entrenched in that world. Guthrie himself dabbled in the esoteric, publishing The Gospel of Osiris and writing the introduction to a once-influential collection of lost and apocryphal scriptures, The Forgotten Books of Eden. Prefiguring much modern scholarly opinion, he thought it impossible to understand the world of Jesus without knowing the book of Enoch and the odes and psalms of Solomon.