(Century illustration)

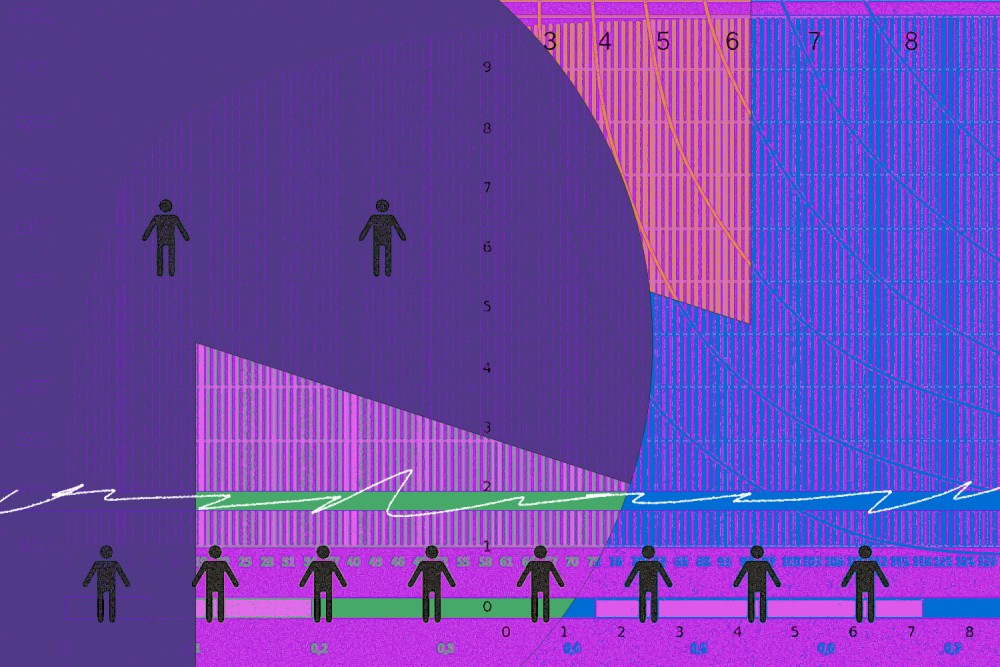

When I started pastoring, at the ripe old age of 27, a more seasoned pastor took me to lunch and gave me some advice. Most of it was really useful. But at the end he said something I’m guessing a lot of readers have heard before. “And one more thing,” he said, “find your leaders. You’ve heard of the 80/20 rule, right? Only about 20 percent of the people are going to do more than just come to worship. They do everything for the other 80 percent, so find them and you’ll be fine.”

It’s not terrible advice. It certainly resonates with what we see happening around us. A vital few do the work for the many. And so it follows that if you concentrate on the few, it will buoy the many. Consciously or not, we faith leaders often abide by this: the members who do the work—or give more money—are considered “more vital” than everyone else. So we cultivate them, to the extent that the 80 percent may feel totally disconnected. We follow the logic of this well-known but widely misunderstood 80/20 rule.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

First, the origins. In 1895, an Italian economist named Vilfredo Pareto recognized that 80 percent of the land was owned by 20 percent of the people. This led other social scientists to notice similar patterns across society, and the Pareto principle, or 80/20 rule, was born. In his recognition of the “vital few” and the “trivial many,” however, it’s important to recognize that Pareto was describing a problem, not a solution.

In church practice, this formula presents a few problems. First, and most important: this way of thinking and organizing isn’t the gospel! Jesus didn’t take 2.4 of his 12 disciples and say, “OK, let’s meet over here and figure out what we’re gonna do.” He invited them all to his ministry. A church where 20 percent of the people are doing all the work may be typical, but it does not reflect the kind of congregation described in Acts 2. The early church was far more communal, and everyone was expected to pitch in as they could. Back then, you might even have gotten called out if all you did was show up on Sunday. Those folks in the Bible are tough!

We’re nicer now, but there’s a second problem with this practice: it burns people out. People will serve in a particular role at church for years, and when they stop it’s not because they want to do something else or feel called to serve in a different way; it’s because they physically can’t do it anymore. Their bodies buckle from carrying the weight of the work alone. And though the solution may be to gracefully thank them and go find someone else, this plays into the same cycle of burnout. The 80/20 rule is a problem of theological anthropology and justice.

Then there’s a third problem. One person does the work, or a small group takes it on, and it becomes trapped inside this thing called a committee. It’s not that the concept of committees is terrible; it’s good to make sure someone is focused on a particular thing. And it isn’t a problem with the word committee; you can call it a “task force” or “team” or “working group” or whatever you’d like. The problem is that whatever you call them, if committees are built around the 80/20 rule, then they become containers for the various arms of the church in a way that is limiting rather than empowering.

If you want to do social justice, go over there. Oh, hospitality? That’s what this other group does. But if that’s what they do, then what does the entire church do? I worry that our typical practice encourages a vital few specialists, while the rest are encouraged to be onlookers. People who say, “I’m glad to be part of a church doing this,” instead of, “I’m glad to be helping my church do this.”

I experienced this far too often in the early years of my pastorate, so some of my lay leaders and I decided to try something different. When we started offering sanctuary to an undocumented immigrant facing deportation, there was a question of who would be in charge. And because we didn’t have anything like an immigration committee at the time, we fumbled a bit. All of our committees were a bit scrambled at the time—longtime chairs were ready to move on, and groups were struggling to attract new members, even as the church itself was growing—so we found ourselves at a crossroads.

We decided that just this once we’d frame an action not as the work of a few on our behalf but as something the entire church would be helping with. We obviously needed some folks to help coordinate logistics, but they were going to shape the work for the rest of us, not do it all themselves. Because isn’t everything the church does part of the church’s ministry? Then no matter who organizes it, it should always end up back in front of everyone.

And then we invited the wider community, from outside our congregation, because neither committees nor congregations should be owning God’s loving work. We quickly realized that there were scores of people who were happy to help us provide hospitality and love. Very few of them joined the planning team, and almost none joined the church officially, but in those moments this was the church—no one would have disagreed. And on Sundays, we brought updates to the gathered congregation so that everyone could be praying and investing in our collective work in other ways.

The result was that the work was done but also that the people involved felt like leaders rather than like the ones responsible for carrying the project. And when that situation ended, they were ready to do it again. It is life-giving to feel like you’re contributing to the whole. It is exhausting to feel like something won’t happen without you.

So let’s stop being satisfied with the 80/20 rule. We should be thinking 100 percent—everybody in—and shaping our ministries to reflect that.