Uniting the new working class

Today's laborers are more likely cleaning toilets than mining coal. But there's still a need to organize.

In a political campaign marked by extremes, the issue of class seems to have turned itself inside out. Union members who supported Bernie Sanders are not necessarily Hillary Clinton supporters—some may turn to Donald Trump in their suspicion of a Democratic Party that has done little for unions lately. “Brexit” and anti-immigrant rhetoric across the globe pit underpaid workers against each other. Can we even talk about a single working class anymore?

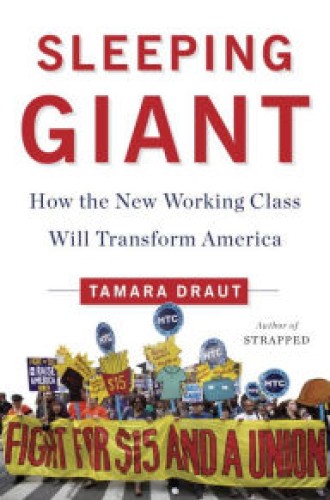

Tamara Draut, an executive at Demos, a public policy organization, believes that we can and must. But it’s not your grandfather’s working class: working men in physically challenging and dangerous manufacturing jobs whose unions ensured that they were compensated fairly across the board.

Today’s working class is more female, more diverse, and less likely to work en masse in a factory. They are paid by the hour with little chance for advancement: checkout clerks, salespeople at the mall, hamburger flippers, and janitors. Many of them earn a living taking care of society’s oldest and youngest members as home health aides or child-care providers. They’re seldom protected by labor laws or unions. They may have to ask permission to take a bathroom break. Draut defines the working class as “individuals in the labor force who do not have bachelor’s degrees.” Say what you will about the cost and value of a college education—it’s still the best predictor of occupation and income.