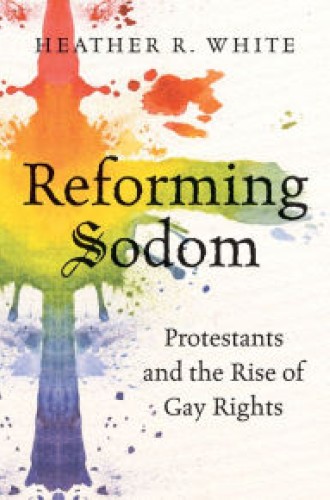

The homophile church

Protestants were deeply involved in the gay rights movement—even before the Stonewall Riots.

In November 1969, the Christian Century published a short article by James S. Tinney called “Homosexuals Convene in Kansas City: Community, Churches Cooperate.” It reported that the fifth annual North American Conference of Homophile Organizations had just convened in Missouri. (Homophile was the term preferred by many midcentury gay activists, in part because it stressed not sex acts but same-sex love, or philia.) Heather White doesn’t mention Tinney’s article in her important study of Protestantism and gay rights in America, but when Tinney’s article is read through the lens of White’s arguments, two facts leap out.

First, Tinney notes that “the church participated” in the conference. Most of the ecclesial representatives were United Methodists. “None of the religious representatives suggested that homosexual activity is immoral,” wrote Tinney, and “all expressed the hope that society in general might be educated to accept homosexuality.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Second, this ecclesial engagement with the homophile movement occurred just months after the Stonewall riots—and by the time Tinney wrote, church support for events like the Kansas City conference was nothing new.

White joins the chorus of historians who argue that although the Stonewall riots are often remembered as the beginning of the organized struggle for gay rights, the movement that appeared to erupt spontaneously after Stonewall relied on years of earlier organizing. White’s crucial innovation is to look at Protestantism in the era before Stonewall. It’s easy to assume that it was secular society that began pushing for gay rights and that eventually mainline churches reacted to, caught up with, or accommodated the trend. White decisively shows that this was not the case. Far from merely reacting to or accommodating Stonewall, mainline churches helped usher in the gay rights movement.

Protestant ministers were among the early activists who agitated for the reform of sodomy laws and for a more generalized acceptance of same-sex love. Through rigorous archival scholarship, White reconstructs the process by which mainline Protestant ministers became political allies of the organized homophile movement.

As White tells the story, a key event in the radicalization of Protestant ministers was a New Year’s ball thrown by and for the homophile community of San Francisco on January 1, 1965. In preparation for the ball, two clergymen met with police, hoping to convince the cops to refrain from raiding the dance or harassing the attendees. The clergymen left their meeting thinking they’d won the argument, but on January 1, the police raided the ball. As the raid unfolded, some local ministers tried to shield guests from police cameras (since photographs could have been used to expose attendees to family, employers, and landlords). Other ministers “escorted guests through the police line to ensure that anyone caught by the cameras went on record alongside the respectable figure of a clergyman.” All in all, hundreds of those who attended the event were harassed, and six people were arrested.

The ministers were appalled by the arbitrary power evidenced by the police raid. The next morning, they began working for reforms that would help the homophile community of San Francisco and would help galvanize “quiet church-based support” for sodomy law reform across the nation.

White’s depiction of Protestants’ gay rights work before Stonewall sets up her account of post-Stonewall activism. She reveals that the movement sparked by the raid on Stonewall “held most of its meetings in churches. Those spaces were available because of earlier networks developed by . . . clergy” who had been working for the reform of sodomy codes since at least the midsixties. Mainline clergy were among the architects of a movement that, it turns out, was decidedly not secular. “A particular Protestant tradition has been a productive source for the twentieth-century politics of sexual emancipation.”

Why, then, is it so easy to assume that the gay rights movement was secular? White addresses that question, too, arguing that as some liberal Protestants were doing early gay rights work, others were helping equate Christianity with hostility toward same-sex practice. For example, in 1946 the translators of the Revised Standard Version introduced the term homosexuals into an English-language Bible, including the term in the list of sinners “barred . . . from inheriting the kingdom of God” in 1 Corinthians 6:9. The word was a combined translation of the Greek terms malakoi and arsenokoitai, which had been rendered in the King James Bible as the “effeminate” and “abusers of themselves with mankind.”

This change in translation prompted a change of interpretation. In 1956 one pastor reminisced about a sermon in which he’d read effeminacy as a warning against “those who take the easy road.” He had loved the sermon—until he’d read the RSV and realized with “chagrin” that the verse was about “homosexuals.”

When translators stitched the term homosexuals into the RSV, the word was itself relatively new, a neologism that had gained currency in early 20th-century medical discourse. Its introduction into 1 Corinthians, argues White, created the sense that homosexuality was a stable transhistorical concept and something the Bible had always univocally condemned. Precisely because of this assumption, much forceful midcentury homophile writing argued that gay liberation was tautologically secular—to be self-actualized, gay men and lesbians needed to rid themselves of a monolithic “Judeo-Christian” opposition to “homosexuality.”

The story White tells in this significant monograph is not a Whiggish account in which liberal Protestants embraced “sexual emancipation.” Mainline Protestantism was on the forefront of gay rights. But mainline Protestantism was also in part responsible for the two-pronged assumption that the Bible condemned something called homosexuality and that to embrace same-sex practice was thus perforce to move away from Christianity. Members of mainline churches owe White a debt of gratitude for showing that “a liberal Protestant legacy has shaped all sides of the oppositional policy over gay rights.” One needs only to read the pages of the Century today to recognize that we are in the midst of this story still.