Moral constructions of HIV

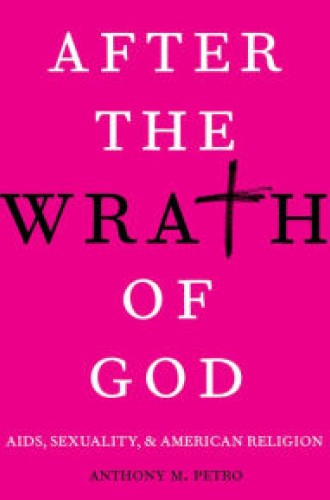

When the Supreme Court decided in June of last year that gay and lesbian people have a constitutional right to marry, activists for gay and lesbian equality won an important battle after a long fight. In After the Wrath of God, a book released just weeks after that decision, Anthony Petro, an assistant professor of religion at Boston University, questions the value of this victory by placing it in the context of AIDS discourse in the United States.

Petro’s key term is moral citizenship. By this he means that discussions of who should receive full and equal rights in the United States are almost always part of a moral discourse about who deserves them, and this is perhaps never more vividly so than in the discourse over rights for gay and lesbian people. He notices how public support for marriage equality was shaped by fear of gay promiscuity, perpetuated by fear of the AIDS virus. “There are many reasons to support gay marriage,” Petro concludes. “But we might ask why it is that the gay marriage movement has become so attached to the narrative of romantic sexual monogamy as the normative model for queer life and how this vision has become the salvific hope for ending HIV/AIDS.”

It seems ironic to talk about a “normative model for queer life.” Perhaps it shows how much the conversation has changed. But Petro calls this embrace of the romantic narrative of gay marriage a “conservative plot” that turns AIDS into a reason to define gay men’s adult sexuality solely by monogamy and marriage. A new argument about “God’s sexual morality” has emerged. AIDS is not God’s wrath, but AIDS demonstrates that God wants all men and women, of any sexual orientation, to express their sexuality only in marriage. While this might be an improvement of sorts over the old argument, says Petro, it has its own costs to queer identity and sexual freedom.