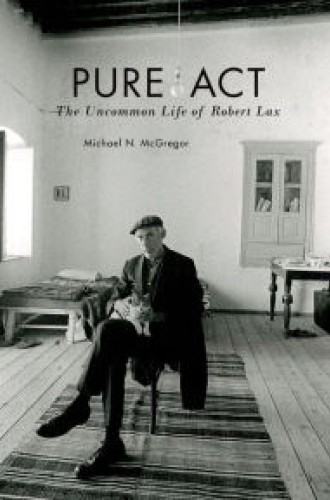

Poetic solitude

My interest in Robert Lax and his uncommon life has for many years exceeded my interest in his poetry, which at its best can open up language and its attendant mysteries in surprising and lovely ways, but at its worst can seem a little silly, and even occasionally a waste of paper. For those of you who don’t know the poetry, I offer this example of the best from an early collection, Circus of the Sun:

The Lord, who created them,

Leaves them in slumber until it is time.

Slowly, slowly, His hand is upon the morning’s lyre,

Makes a music in their sleeping.

One of his worst poems, from a later collection—Poems (1962–1997)—consists of a sequence of alternating tercets, each simply repeating the word no or yes.

One might wonder why a poet with so engaging a voice, so rich and compassionate a vision, would forsake a promising literary career for an isolated vocation worked out in obscurity, writing texts that few besides himself might savor.

Michael McGregor offers something of an explanation: Lax—beloved friend of Thomas Merton, most gifted student of Mark Van Doren, early and frequent contributor to the New Yorker, and a man who could count E. B. White as a fan—suffered no shortage of ambition, but it was a profoundly unusual sort. Early on in their friendship he told Merton that “all he had to do to become a saint was to want to be one.” Lax appears to have honored his own counsel.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

McGregor’s title, Pure Act, alludes to an observation by Thomas Aquinas: “God, Aquinas wrote, is pure love and pure act, while all else in the universe languishes in potentia [sic]. When we act consciously and yet spontaneously, Lax thought, we become pure ourselves—we become like God. If, that is, we act in love.”

McGregor tells us that from his youth Lax experienced a love of God that would not abate. Initially he embraced Judaism, leaning into a more Orthodox practice than the Reform Judaism of his childhood home. He also began to read the Bible—both Old and New Testaments—slowly and carefully and came to see that “Judaism and Christianity were not contradictory but complementary.” He was not yet a Christian, but he became enamored of Jesus, so much so that when he saw the United States being drawn into World War II, he could not find it in his heart to justify killing for any reason, and he especially rejected the argument that one might kill virtuously. Lax “chose instead to believe, without dilution or emendation, what he read in the Bible, what Jesus taught: that in all circumstances, without exception, we are called to live a life of total love.”

In August 1940 the U.S. Senate passed a bill authorizing the draft. Lax wrote the following in his journal: “I believe this. That the world will be good when men cease from evil, that other men cease from evil when you do, and that you can be good more and more easily by wanting to: by ‘loving the Lord, thy God, with all thy heart, with all thy soul, and with all thy might.’”

Even beyond the repercussions of being a conscientious objector in a country set on war, Lax’s unwavering resolve did not result in an easy life. Lost jobs, career confusion, and internal dissonance all took their toll; he experienced his own dark night of the soul. Despite this—or more likely, because of this—the “total love” that had led him into this bleak valley also attended his sojourn there and began to lift him out. He gave himself to serving the poor of Harlem throughout much of 1942 and into 1943. Shortly thereafter, Lax found further consolation and joy in his baptism into the Catholic Church. He wrote to his father that “joining the Church was the best way for me to be a good Jew.”

McGregor makes a fascinating and compelling distinction about the uncommon life that Lax would eventually pursue. “Although Lax has often been called a hermit, a solitary might be a more accurate term.” A solitary life allows for the contemplative’s need of solitude as well as for remaining in touch with people.

In his essay “Notes for a Philosophy of Solitude,” Merton makes a persuasive case for what he calls a solitary life. Lax departed in 1961 for Greece, where he found the uncommon life to which he had long been called. McGregor writes, “[Lax] was already spending much of his time alone, but his aloneness has a sadness to it; Merton was describing a solitary existence filled with peace and joy.” Lax would spend time on Lesbos, on Kos, on Kalymnos, and elsewhere, but his eventual home would be Patmos, final destination for St. John the Divine.

As I read of Lax’s life in Greece—and what I would call his compassionate disinterest—I am reminded especially of St. Isaac the Syrian, who wrote:

Suffer with the sick.

Be afflicted with sinners.

Exult with those who repent.

Be the friend of all, but in your spirit remain alone.

Be a partaker of the sufferings of all, but keep your body distant from all.

I genuinely love St. Isaac. I have pored over his words many times, but I have sometimes been puzzled by such gestures as “in your spirit remain alone” and “keep your body distant from all.” They seem to contradict the compassion that is so vividly at the heart of St. Isaac’s ascetical homilies. McGregor’s careful presentation of Lax’s uncommon life has helped me to understand this puzzle.

Even today some are called to an ascetic journey. I am reminded of the fathers of Mount Athos, who appear to be cut off from us but who spend their lives praying for us. I am reminded of Orthodox monastics worldwide, whose tradition promotes nepsis: watchfulness, the guarding of the heart. This is a practice of circumspection coupled with introspection, which enables the ascetic to protect his interior life from the distractions of happenstance. With examples such as Lax, one might find the practice to be efficacious for any who would follow the admonitions of the scriptures and attain to a measure of holiness—even now, even here.

Pure Act is an homage, a love letter, an apologia for a curious poetics, and a well-considered story about an uncommon man and his very uncommon life. For us, it may prove something of a wake-up call as well.