The feminist Bushnell

Conventional wisdom chalks up the estrangement between Christianity and feminism to historical inevitability. But a century ago, Katharine Bushnell, a Holiness Methodist missionary doctor, addressed the “challenge of Christian feminism” by attacking mistranslations of the biblical texts that were used to justify women’s submission to men. She worked to hold feminism and Victorian Christianity together, joining the former’s claim for women’s full humanity to the latter’s message of Christ’s salvation for all people.

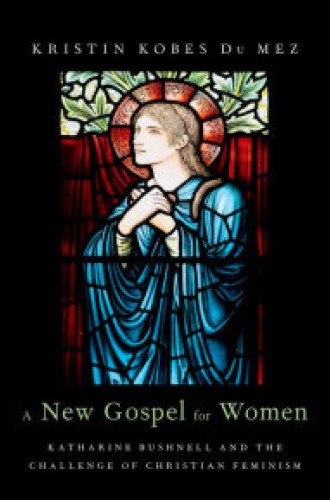

Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s book includes biographical information about Bushnell—a distant relative of Horace Bushnell, one of liberal Christianity’s primary early exponents—but also provides extensive glosses on her retranslations and exegeses of biblical texts. Despite some resulting unevenness, the book offers a compelling portrait of a reforming whirlwind who left the mission field to campaign for temperance and against the sex trade and the sexual double standard.

Bushnell’s relatively brief time as a missionary doctor in China, from 1879 to 1882, convinced her that a misshapen Christianity harmed not only women abroad but also women in the United States by subjecting them to unbiblical male authority. Soon after arriving in the Yangtze River port city of Kiukiang, Bushnell discovered in a Chinese translation of the Bible what appeared to be a concerted effort to hide women’s equal participation in the early church, as described in Philippians 4. This discovery set her on a lifelong study of Greek and Hebrew biblical texts.