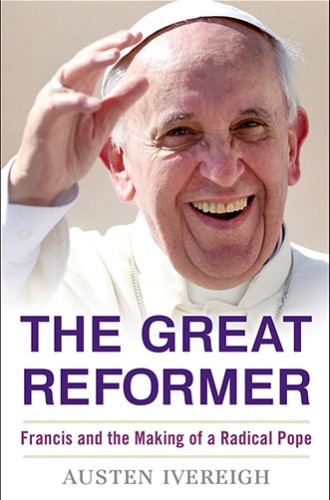

The Great Reformer, by Austen Ivereigh

Chief among the multiple revelations in this book is that its author was tipped off about the identity of the new pope before the decision of the Vatican conclave was revealed. Austen Ivereigh is a former adviser to the retired archbishop of Westminster, Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, a cardinal who was involved in 2013 preconclave meetings but was too old to participate in the actual conclave that chose Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Between the appearance of the white smoke and the revealing of the new pope, Ivereigh reports, Murphy-O’Connor tipped him off that it might just be Bergoglio. This is the first time Ivereigh has put this anecdote—previously told only to friends—in print.

This tip was not the only thing that prepared Ivereigh to say something knowledgeable about Pope Francis from St. Peter’s Square for a British news channel just seconds after the new pontiff emerged from behind the curtains on the balcony—while quite a few talking heads bungled things in those first moments. The months that Ivereigh had spent living in Buenos Aires 20 years earlier researching a dissertation on Argentinian politics and the church helped him as well.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Also important to The Great Reformer, the most expansive and important biography of Bergoglio yet published, are Ivereigh’s claims about what happened in the secrecy among the cardinals before and after Bergoglio’s election—claims now denied by a Vatican spokesperson. The claims have led to a small controversy involving the author, Cardinal Murphy-O’Connor, and Pope Francis’s office. Ivereigh seems to have overstepped the boundaries of friendship and confidence in the writing of his book. Even Murphy-O’Connor’s press secretary (probably a former colleague of Ivereigh’s) has insisted that some of what Ivereigh wrote about his old boss is not accurate. Everyone is in an awkward spot. I suspect that Ivereigh overreached to arrive at original conclusions. Either that or he didn’t realize the problems he might cause by telling the tales.

The troublesome central issue is a purported behind-the-scenes campaign before and within the 2013 conclave to support Bergoglio—who Ivereigh states conclusively was the runner-up to Ratzinger in 2005—as well as the suggestion of a conversation between Bergoglio and certain cardinals in which they asked him if he would accept the position if it were put to him. Ivereigh writes that Bergoglio responded to the effect that no cardinal could refuse such a request during a time of crisis for the church.

Campaigning has, of course, always been common in conclaves, as well as in papal elections not held in conclave in centuries past. Conclave (Latin cum clave; English “with a key”) figuratively means “behind locked doors.” But a prospective pope is never supposed to campaign for himself or participate in his own election, and Ivereigh makes it sound as if Bergoglio was almost urging along what some cardinals had in mind.

The Great Reformer was published at the end of November. On December 1, Vatican spokesperson Federico Lombardi issued a statement saying that all of the cardinals mentioned in Ivereigh’s account “have expressly denied this description of events, both in terms of the demand for a prior consent by Cardinal Bergoglio and with regard to the conduct of a campaign for his election.” The following day Ivereigh told Religion News Service that he regretted how he had phrased the scene and that he’d alter it upon reprint, removing any reference to cardinals expressly asking Bergoglio about his intentions.

This substantive, 450-page biography also addresses Bergoglio’s conflict with Jesuits earlier in his career. A former Jesuit himself, Ivereigh is in a good position to understand Bergoglio’s Jesuit background, as well as the reasons he cut himself off from much of the order between 1992 and his election as pope. In Ivereigh’s account this story receives the fullest treatment it’s seen to date, at least in English.

The estrangement took place in 1992 after Bergoglio was made a bishop in Buenos Aires. Ivereigh tells us that Bergoglio was hardly known by most Argentines before 1992, and that only one other Jesuit had ever been made a bishop in Argentina. There must have been some professional jealousy, and soon Bergoglio was accusing the new Jesuit provincial, Ignacio García-Mata, of defaming him in a report to Rome. García-Mata had been asked to accommodate Bergoglio in the local Jesuit house until Bergoglio’s new rooms were ready for him. But García-Mata quickly found Bergoglio to be an “interfering” presence in the ongoing work of the province, and he eventually asked him to leave. Ivereigh’s endnotes reveal that one of his sources for this narrative is an interview with García-Mata himself.

Every page of The Great Reformer is interesting. The book is beautifully written, well crafted from beginning to end. The title, however, is curious; I wonder if it was designed to appeal to non-Catholics. Ivereigh’s point is more aptly expressed in the subtitle. Throughout his life, Jorge Mario Bergoglio has done what we see him doing so publicly now as Pope Francis. He has long desired to be a radical man of faith, seeking reform within the church and championing the poor regardless of whether it would further his career. Apparently, it’s worked out all right for him.

The fact that such a man made it all the way to the Chair of St. Peter says as much about the desperate state of the church in early 2013 as anything else. This is the tone we pick up from those possible secret conversations among the cardinals to campaign for and recruit an Argentinian radical for highest office. Ivereigh clearly wants to bolster this perception and is a champion of the reforms happening throughout the church thanks to Pope Francis’s influence and example for change.