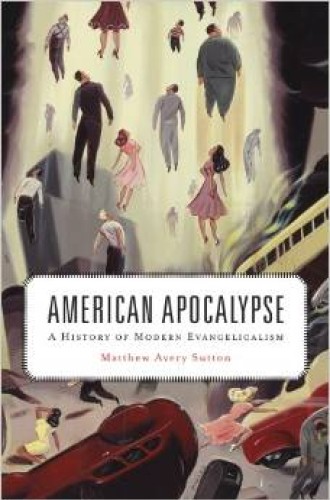

American Apocalypse, by Matthew Avery Sutton

Why do most white evangelicals vote Republican? How has this affected Republican politics? In American Apocalypse, Matthew Sutton, author of a prize-winning biography of Aimee Semple McPherson, gives us our first good account of how and why evangelical political views developed the way they did. Three elements were crucial—premillennial eschatology, World War I, and the Puritan heritage. Oh, and a fourth: white evangelicals were not African American.

The book opens by describing a new way of reading the Bible called dispensational premillennialism, which became popular in the late 19th century. Leaders of this movement came primarily from the two holiness traditions—Wesleyan holiness and its Pentecostal offspring, and Keswick (Higher Life) holiness, a British variant. Sutton calls these folks “radical evangelicals,” and for good reason. Many of their ideas and attitudes put them outside the norms of conservative middle-class Protestantism.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Sutton notes that dispensationalism was anything but conservative. In an era when most Christians thought the world was getting better, dispensationalism taught that it was getting worse. The Bible predicted that unprecedented natural disasters, accelerating wickedness, global wars, social chaos, apostasy of churches, Jewish reconstitution of Israel in Palestine, and a new European empire ruled by the Antichrist would finally culminate in the rapture, when true Christians would supernaturally rise to meet Christ in the air. Then, after a seven-year period of totalitarian oppression and world conflict, Christ would return, defeat the Antichrist in the earth-shaking battle of Armageddon, and inaugurate the millennium.

It is startling to realize that premillennialists were making these predictions in the 1870s before the development of liberal theology, two world wars, global economic crises, the rise of totalitarian states, creation of the nation of Israel, a nuclear arms race, the threat of environmental catastrophe, and rapid social change. These developments understandably convinced premillennialists that they were right. Sutton argues that this gave them absolute certainty that they alone were correctly interpreting the Bible.

Sutton also shows that it energized them to strenuous action. Their key Bible verse here was Jesus’ injunction to “occupy till I come.” In the 19th century this meant aggressive evangelizing at home and abroad so that as many as possible could be saved from the suffering and destruction of the seven-year tribulation following the rapture. To accomplish this they built a large network of independent missionary organizations and Bible institutes.

But they did not just evangelize. They also kept watch on how contemporary events were fulfilling prophecy, and this naturally led them to comment on political developments. Because their premillennialism and independent organizations placed them outside the mainstream of middle-class Protestantism, they felt no particular compunction to align with conservative middle-class politics. So while mainstream Protestants in the late 19th century urged the government to crack down on unions, premillennialists were as likely to side with workers and rain invective on rapacious capitalists. At the turn of the century many premillennialists made common cause with Progressive campaigns against political corruption, urban vice, saloons, and corporate monopolies. And when the United States finally entered World War I, premillennialists tended to be skeptical about American war aims; some were even pacifists.

But the war and its aftermath, Sutton argues, proved to be “the central pivot” for the premillennial movement. Liberal church leaders and premillennialists accused each other of being unpatriotic, and in the process premillennialists shed their skepticism about America. They adopted the old Puritan view that God had chosen America for a special destiny. Meanwhile contemporary events—the shocking devastation of the war, the new communist dictatorship in Russia, the rebellion against Victorian manners and morals (think flappers and risqué Hollywood movies), and the victory of theological liberals in the fundamentalist-modernist controversies convinced premillennialists that they were living in the end times.

The political impact was that premillennialists (now often called fundamentalists) stepped up their criticism of moral decline and aligned themselves with the Republican Party. Unionized workers all of a sudden looked like Bolsheviks, so premillennialists began defending corporations and the wealthy. They adopted another Puritan conviction—that government should regulate morality—and staunchly defended Prohibition. Two presidential elections cemented them to the GOP. The Democratic candidate in 1928, Al Smith, was a Catholic who favored repeal of Prohibition. And the Democratic candidate in 1932, Franklin Roosevelt, favored not only repeal but also aggressive government intervention in the economy. In the era of Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin, premillennialists thought Roosevelt was a dictator-in-the-making and his New Deal the beginning of American socialism.

Premillennialists emerged from World War II into the cold war era with a new name—evangelicals—and with new organizations and an expanded program for evangelism and social action. Key leaders included Boston minister Harold Ockenga, theologian Carl F. H. Henry, and editor L. Nelson Bell and his son-in-law Billy Graham. Oilman J. Howard Pew, a fervent opponent of the New Deal, was a key benefactor. Together they established the National Association of Evangelicals, Christianity Today magazine, and Fuller Theological Seminary. They continued to evangelize, but now for the purpose of “revival.” By this they meant a religious awakening and moral reformation that would renew the national character. They also advocated for change in the nation’s political, moral, and intellectual direction. They forged a political ideology that made limited government, free enterprise, and religious freedom its first principles. They preached liberty in economic matters but government suppression of immorality. In foreign policy they championed interventionist unilateralism. “Occupy till I come” became “occupy the nation till I come.”

Premillennialism could thus be adapted to a variety of political frameworks. Sutton also demonstrates its adaptability by tracing the very different path of African-American premillennialism. Black premillennialists commonly believed that God’s faithful end-times remnant would be African, that America was the seat of the Antichrist, and that African Americans were already living in the tribulation (think Mississippi in 1964). They often viewed white racism as a sign of the end times and government protection of their civil rights as the liberating hand of God. White evangelicals, by contrast, did little to roll back the practices or effects of racism. Most opposed the civil rights movement, fearing that it was communist-led and dangerously expanded the reach of the federal government.

By this time white premillennialists, having transitioned from radical evangelicals to fundamentalists to new evangelicals, had become right-wing Republicans. They now believed, Sutton tells us, that “the destiny of the nation . . . was in their hands.” Their political activity, which started out as commentary and at mid-century became advocacy, finally in the 1970s became mobilization when they were recruited and organized by the conservative wing of the GOP. This gave us the religious right and the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush.

It also transformed the American political climate. Sutton argues that evangelicals’ apocalyptic theology gave their politics “the urgency, the absolute morals, the passion to right the world’s wrongs, and the refusal to compromise” that now defines right-wing politics. But of course influence runs in both directions. Evangelicalism has given the Republican Party a new moralistic absolutism, while the right wing of the Republican Party has given evangelicalism a new hardness of heart. Time will tell if these are steps toward revival or toward apocalypse.