Historian with a cause

At the business meeting of the 1969 annual conference of the American Historical Association, Boston University historian Howard Zinn, representing a group called the Radical Historians’ Caucus, tried to convince the AHA to champion a resolution calling for the United States to withdraw troops from Vietnam. The motion was defeated, but the attempt to get it passed resulted in high drama—the kind of intense conflict not often seen at the business meetings of the AHA.

Debate continued until well past midnight, and just as the meeting was about to adjourn, Zinn grabbed a microphone and pleaded with the members to reconsider the resolution. This prompted AHA president and Harvard historian John Fairbank to wrestle the mic from Zinn’s hands and bring the meeting to a close.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Eugene Genovese was one of the historians in attendance who vocally opposed the resolution. A distinguished historian of the American South, one of the nation’s foremost Marxists and a leading opponent of the war in Vietnam, Genovese spoke as a historian when he declared that such a formal statement of opposition to the war would unnecessarily politicize the profession. Calling the association’s radicals “totalitarians” and exhorting the AHA membership to “put them down, put them down hard, once and for all,” he sent a message about the vocation of the historian.

Though Genovese was one of the most politically active academics in the United States, he rejected the “cynical conclusion that all scholarship is subjective and ideological.” Historians, he believed, should not use their scholarship to promote political causes.

Zinn and Genovese represented two very different ways of thinking about the relationship between the past and the present. Although Genovese believed that the past has something to teach us, he worried that present-minded history would lead to what historian Bernard Bailyn once described as “indoctrination by historical example.” The radicals, Genovese believed, were prone to cherry-picking the facts that conveniently supported their political agenda. Real historians examined the past in all its fullness. Zinn, on other hand, called for a “value-laden historiography”: he chided his fellow historians for “endless academic discussion” and “trivial or esoteric inquiry” that “goes nowhere in the real world.”

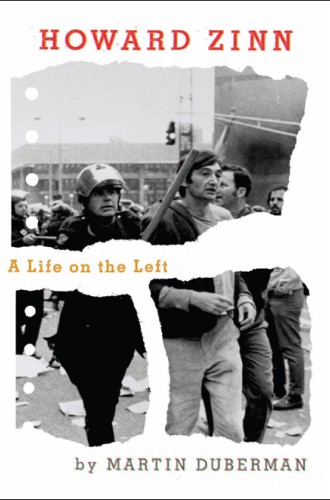

Martin Duberman has written the first biography of Zinn since Zinn’s death in 2010. Duberman does not try to hide the fact that he and Zinn were friends (he calls him Howard throughout the book) who shared the same political values and a similar skepticism of so-called objective history. He treats Zinn with kid gloves in this book, but he does not completely shy away from criticism.

Zinn was born in 1922, the child of working-class Jewish immigrants who eventually settled in Brooklyn. His experience as a bomber pilot during World War II led him to become a pacifist; he concluded that “war cannot be humanized, it can only be abolished.” He was a strong critic of Harry Truman’s cold war policies, and though he never joined the Communist Party, he supported several communist candidates, prompting the FBI to open a file on him in 1949. Zinn attended college on the GI Bill and eventually received a Ph.D. in history from Columbia. He began his teaching career at Spelman College, a historically black institution in Atlanta.

Zinn became a civil rights activist during his tenure at Spelman and developed a strong working relationship with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Atlanta. However, the Spelman administration wanted Zinn to teach history, not organize students for civil rights protests. As a result, he was fired in 1963. Shortly thereafter he landed a job at Boston University, where he would spend the rest of his academic career in battles with administrators over everything from faculty salaries and free speech to military recruiting on campus and Zinn’s regular absences from the classroom.

For Zinn, civil disobedience was as American as apple pie. He regularly invoked events from the American Revolution to justify his participation in social movements that championed a more democratic United States. In 1968 he and Catholic priest Daniel Berrigan traveled to Hanoi at the request of the North Vietnamese government—which wanted to negotiate with members of the American peace movement—to collect three captured American pilots. The move drew much media coverage and prompted both liberals and conservatives to question Zinn’s patriotism. A few months later Zinn took responsibility for hiding Berrigan, his brother Philip and seven of their friends after the group, known as the Catonsville Nine, entered draft board offices in Maryland and set fire to hundreds of draft records.

Zinn never met a protest rally he didn’t like. He was a regular speaker at civil rights marches, anti–Vietnam War gatherings and other New Left rallies. According to Duberman, Zinn was very good at criticizing the many social ills that plagued the United States, but he was not very good at formulating constructive solutions. “He drew enticing pictures of what an ideal society might look like,” Duberman writes, “though without any guidelines for how to get there.”

This biography suggests that Zinn would have been just another 1960s-style activist—an important figure, but not a household name—if not for the amazing success of his 1980 book A People’s History of the United States. Zinn set out to bring the voices of Native Americans, slaves, factory workers and immigrants into the story of the American past.

The book has sold over 2 million copies and has appeared in multiple editions. It has also entered the public consciousness through its mention by Matt Damon’s character in the movie Good Will Hunting and by Tony Soprano in the HBO series The Sopranos. Well written, dramatic, and filled with morality plays, A People’s History is the kind of narrative of the American past that most Americans want to read.

Zinn never claimed that he wanted A People’s History to replace traditional textbooks. He only wanted to see it used as a supplement to standard texts. But A People’s History has become wildly popular among teachers of American history. About ten years ago, during one of my stints grading United States history advanced placement exams in Texas, hundreds of educators signed a petition to invite Zinn to speak to that yearly gathering of AP teachers and college professors. As far as I know, the petition was unsuccessful, but it did reveal Zinn’s immense appeal.

A People’s History has been harshly criticized by historians on both the left and the right. Michael Kazin, a Georgetown University history professor and an editor of Dissent magazine, described A People’s History as “bad history, albeit gilded with virtuous intentions.” Kazin compared Zinn’s perception of American elites to “the medieval church’s image of the Devil” and concluded that “Howard Zinn is an evangelist of little imagination for whom history is one long chain of stark moral dualities.”

Stanford education professor Sam Wineburg, the country’s leading voice in the field of history education, claimed that A People’s History is defined by “yes-type questions,” the kind of questions that send the historian into the past “armed with a wish list.” As Wineburg puts it, “those who ask yes-type questions end up getting what they want.” He chided Zinn for writing with “thunderous certainty” and for substituting “one monolithic reading of the past for another.”

Duberman also criticizes A People’s History of the United States, but he is not as harsh as Kazin and Wineburg. He admits that the book is a simplistic rendering of history in which Zinn often proposes “black and white answers.” Duberman is quick to point out that Zinn’s attacks on the so-called American dream fail to recognize that many immigrants did indeed find a happy and fulfilling life on American shores. He also criticizes Zinn for being so wedded to a story driven by race and class that he virtually ignored religion, ethnicity, feminism, and the gay-rights movement. But Duberman also defends his friend against critics, like Genovese, who claimed that Zinn’s survey of U.S. history was too subjective and ideologically driven.

Sometimes Duberman’s praise for Zinn’s “life on the left” leads him in directions that might cause readers to raise an eyebrow. For example, an entire generation of social historians in the 1960s and 1970s wrote deeply researched, nuanced and groundbreaking treatments of class, poverty, race and slavery—and they might well be offended by Duberman’s suggestion that Zinn should get the “lion’s share of credit” for the revision of history textbooks.

The biography is filled with diatribes in which Duberman veers from his subject to endorse the causes that Zinn championed; it left me wondering whether I was reading a work of history or a political tract. And in one of the most unusual passages of the book, Duberman justifies Zinn’s extramarital affairs by appealing to psychological studies affirming that short-term sexual relationships outside of marriage are a “successful formula” for “maintaining a good lifelong relationship” with one’s spouse.

There will inevitably be future biographies of this self-proclaimed radical that will benefit from being farther removed, in terms of both chronology and personal acquaintance, from their subject.