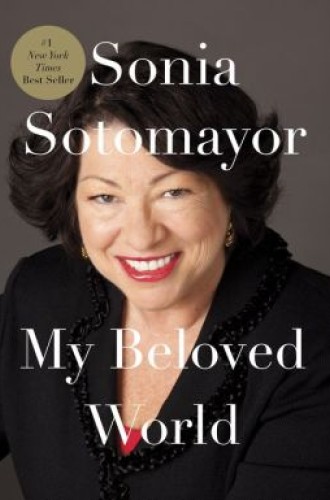

My Beloved World, by Sonia Sotomayor

Celebrity memoirs often appeal to readers’ basest motives. They hope to discover some secret formula for success. Or they want to know whether the author took revenge on enemies or intimates. If the author is a public figure, readers are on the lookout for clues to an ideological bent or personal grievances that will make the author’s future decisions predictable.

If you’re expecting to find such revelations in the memoir of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, you will be disappointed.

If, however, you are intrigued by the question of how a little girl from the projects in the Bronx grew up to be one of the most influential people in the country, you will enjoy this narrative. And if you love to listen to a powerful story told with passion and compassion, simply yet lyrically, as though you were sitting across from the author in a café in New York City, you will turn each page of this book with pleasure.