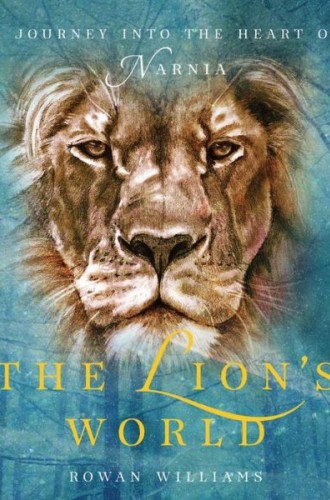

The Lion’s World, by Rowan Williams

Who would have thought that a new book on C. S. Lewis could bring fresh, even revolutionary insight to perhaps the most overstudied Christian writer in the anglophone world? The Lion’s World is such a book.

Countering Christian acolytes, who hail Lewis as the super-certain apologist, and Philip Pullman–like detractors, who damn Lewis as a poisonous racist, sexist and sadomasochist, Williams contends that there is a largely undiscovered Lewis to be found in his Narnia novels. Williams confesses that the Narnia books lack the rich mythography of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, that they contain bothersome inconsistencies and infelicities and that Aslan sometimes resembles a sword-wielding Crusader more than a crucified Lord. Even so, they furnish what Lewis’s formal defenses of Christian faith often lack: a convincing encounter with the disruptive and subversive truthfulness that is God and God’s world. They enable readers to experience the depth and difficulty of belief, to sense the complexity of human and divine realities that Lewis elsewhere turns into ghostly abstractions.

Williams never mentions the books on which Lewis’s reputation as an apologist largely rests: Mere Christianity, Miracles, The Problem of Pain. For him, the best of Lewis is located in his fiction: The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, That Hideous Strength, Till We Have Faces, but principally the Narnia books. This is not to say that Williams regards these more imaginative works as illustrations of Lewis’s theological ideas. They are not easy allegories offering coded links between Aslan and the incarnation, or between his death and the doctrine of substitutionary atonement. Instead, they are stories whose moral truth and religious insight emerge from plot and character, from scene and tone and atmosphere.