The culture of the mainline

Why don’t they listen?” Cosmopolitan elites the world over have asked this question about their provincial constituencies. But no such elite in any time at any place had more cause for exasperated puzzlement than the men and women leading the mainline Protestant churches of the United States in the middle decades of the 20th century. The people in the pews seemed to be following well enough through the 1940s and early 1950s. Congregations were even growing, especially in suburbs. But in the late 1950s churchgoers revealed dismaying limitations. Despite decades of earnest instruction on what a mature faith looked like, many of the faithful couldn’t quite get what was so dreadful about Billy Graham.

The ignorance and bad taste of the flamboyant southern preacher was carefully explained by Reinhold Niebuhr in several forums and by a host of writers for the leadership’s redoubtable (unofficial) house organ, the Christian Century. Yet within a single generation after Graham’s astounding triumph at a New York revival in 1957, when his television audience reached 10 million per week, the public face of Protestantism was largely that of the Graham-led evangelicals and their own magazine, Christianity Today. In the meantime, there was another, comparable failure to pay heed: a very different, younger segment of the community of faith did not get what was so bad about secularism. This had been another of the lessons taught by Century writers, but from the mid-1960s onward many of their own children drifted into varieties of post-Protestant nonaffiliation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

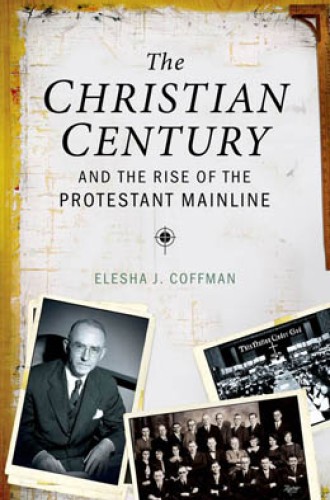

Just how and why all this happened is a matter of ongoing, sometimes contentious debate, enriched now by the intervention of Elesha J. Coffman. The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline is happily distinguished by its sustained attention to the character and dynamics of the great gap between an educated elite and a mass population of churchgoers.

Coffman’s “cultural history of the Christian Century to 1960” treats this magazine as a window through which this portentous gap is uniquely visible. She documents the desire of Charles Clayton Morrison, the editor and owner from before World War I until 1946, for the magazine to serve the “intelligentsia” of American churches. Coffman demonstrates how the Century’s “ability to model sophistication” allowed it to function as a powerful agent of integration, helping to create a transdenominational solidarity of forward-looking seminary professors, ministers and church officials. Although its circulation rarely reached 40,000, its readership included the most highly educated leaders of the Congregationalists, Northern Baptists, Disciples of Christ, Episcopalians, Methodists and Presbyterians, and of some of the Lutheran and Reformed bodies.

Coffman’s animating insight—that these people were proud of their education and acted accordingly—is far from new. But this truth has often been downplayed, if not obscured by a fear that emphasis upon it might call into question the leadership’s concern for the average Methodist and Presbyterian. After all, elitists are hard to love.

Coffman does not fault the Henry Pitney Van Dusens and John C. Bennetts and G. Bromley Oxnams of American Protestantism for their attention to modern learning, but she shows that by 1960 the seminarians and church officials gathered around the Century had been rendered complacent by a quarter century of experience as a formidable presence in American life, recognized by government and media as major players in the mobilizations of World War II and the cold war. She provides a fine account of this leadership’s befuddlement by Graham’s ability to command the sympathetic engagement of rank-and-file mainliners as well as Southern Baptists and Pentecostals. She pointedly reminds us how the money of oil magnate Howard Pew enabled Christianity Today to blast onto the scene in 1956 with a circulation larger than the Century’s even from the start, reaching an audience for whom education was less central to cultural identity than perceived orthodoxy.

But Coffman says little about two other historic realities that a more capacious study of the Century’s circle might have addressed. One is the size and coherence of the leadership’s top-down political and social initiatives of the 1940s and 1950s. From Coffman’s account, one would not grasp the significance of the Federal Council of Churches’ formal condemnation of racial segregation in 1946. (The FCC and some of its affiliated denominations had been railing against racism for many years, but the FCC had previously stopped short of officially calling for an actual end to legal segregation.) Moreover, a reader of Coffman will not learn the extent and character of the leadership’s impact on the United Nations Charter and on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to which she refers only briefly at the very end of the book. Coffman also breezes past the creation of the World Council of Churches in 1948, a major event produced largely by her cast of characters and a key development in the expanding gap between a globally conscious elite and a locally focused rank and file.

In 1958 the National Council of Churches became the first national organization of comparable standing to call for the United States to give diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China, but Coffman misses the significance of this action and the ferocity of the reaction of evangelicals. Coffman alludes to the ecumenical leadership’s leftward activities of the period after 1960, but in the 1940s and 1950s that leadership actually pursued a political course highly relevant to her theme—and visible in the pages of the Century.

Coffman slights a second pertinent reality: the growing intellectual authority of non-Christians in the educated class of which the ecumenical leaders were proud to be a part. Coffman notes that to Morrison in 1946, “secularism” seemed “more diffuse” than Catholicism, the other major threat to Protestant cultural hegemony, “but also easier to combat.”

This remarkable obliviousness on the part of Morrison and many of his successors is basic to any sound understanding of the destiny of their tradition. Coffman attends carefully to the leadership’s preoccupation with Catholicism, right down to the time of John F. Kennedy’s election as president. But her fleeting reference to “the Beat Generation” fails to engage a massive development in the 15 years after World War II: the prominence achieved by Hannah Arendt, Daniel J. Boorstin, Richard Hofstadter, Sidney Hook, Walter Kaufmann, Ayn Rand, David Riesman, Leo Strauss, Lionel Trilling, Morton White and a host of other writers of Jewish origin who combined with lapsed Protestants like John Rawls, Talcott Parsons and Edmund Wilson (along with Beats like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac) to create a national academic and literary intelligentsia very different from the one to which the Century was designed to provide a distinctly Protestant point of entry.

These Jewish and post-Protestant intellectuals were just as committed to education as were the men and women who wrote for the Century. But when these secular thinkers talked about the fashionable new existentialist movement, they had in mind the flaming atheist Jean-Paul Sartre, not the theologian Søren Kierkegaard or the faith-respecting Karl Jaspers. The college-educated children of the Protestant establishment were paying closer and closer attention to this intelligentsia well before 1960, as was clear in the pages of the Century’s junior partner in journalism, the Methodist youth magazine motive.

The later drift of these younger Protestants away from the faith, so compelling traced by recent demographers, is no less dramatic an episode in American religious history than the rise of the evangelical right. The greatest of the ecumenical Protestant intellectuals, Reinhold Niebuhr, may have believed that his criticisms of John Dewey had served to contain secularism. But in fact, he was no more successful in warning one segment of his flock against Dewey than he was in warning another segment against Graham.

Coffman perpetuates the use of mainline, but the awkwardness of this term demands attention. She is correct that as a practical matter from the time the term caught on about 1960 everyone has understood the kinds of Protestants to which it refers. But mainline gains its semantic traction from its association with a strong socioeconomic position and political connections, not from any religious properties of the object named. Moreover, the term lacks a credible opposite; the antonyms to main are auxiliary, extra, insignificant, minor, secondary, subordinate and unimportant, none of which work as a description of the kinds of Protestants who are not mainliners.

Mainline could easily be replaced by ecumenical, which works nicely as a contrast to evangelical, an old, once widely honored adjective that was effectively narrowed and claimed from the 1940s onward by a cluster of fundamentalist, Pentecostal, holiness and other persuasions united largely through their opposition to the styles of ecumenism advanced by the so-called mainline. Ecumenical at least identifies a specific, centrally important, shared commitment and connotes the openness to cultural diversity that helped distinguish mainliners from their critics going all the way back through the modernist-fundamentalist debates of the 1920s.

Distinguishing between “ecumenists” and “evangelicals” need not imply that the groups associated with the National Association of Evangelicals have been unable to mount ecumenical programs of certain kinds, nor that the groups associated with the National Council of Churches have been altogether aloof from evangelism. But this pair of terms does denote the most prominently proclaimed, specific programs of each party, offers each party the modicum of respect conferred by avoiding labels popularized mostly by one’s enemies, and sidesteps the confusion attendant upon the use of liberal and conservative, which, while conveying some genuinely pertinent theological and political freight, lacks the religion-intensive character of ecumenical and evangelical.

A sustained analysis of the destiny of ecumenical Protestantism after 1960 is beyond the scope of Coffman’s book and of this review. Coffman appropriately notes that as early as 1958 Martin Marty, as a junior editor of the Century, voiced the opinion—later to become very popular—that ecumenists could function well as a prophetic minority “in a pluralistic, post-Protestant society.”

Coffman also observes, correctly, that the ecumenical elite helped to shape post-Protestant America even while relinquishing control of the bulk of the symbolic capital of Christianity to its evangelical rivals. She is probably wise not to push too hard the questions of what the ecumenical leadership might have done differently—and with what results. But this judicious, fair-minded, carefully documented book provides plenty of material to those who continue to debate those questions.