Prophetic epistle

Read "Letter from Birmingham Jail" as it appeared in the Century. See also Robert Westbrook's cover story on the letter's 50th anniversary.

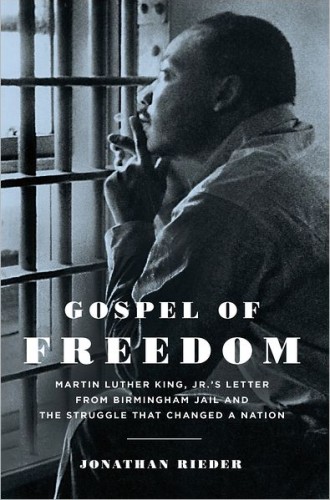

Martin Luther King Jr. lived less than four decades, and his public life spanned only 13 years, ending in 1968. In that time, the Baptist minister turned civil rights activist pricked the conscience of an America that was just a hundred years removed from Civil War and still wrestling to make real its creed that “all men are created equal.” One of King’s most piercing proclamations of his faith-tinged message of nonviolent resistance was “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” a letter written in the tradition of the apostle Paul’s prison epistles. Barnard College sociologist and historian Jonathan Rieder surveys the events that gave rise to King’s message and offers a fresh perspective on the substance of the letter itself, which “provided nothing less than the moral and philosophical foundations” of the civil rights movement.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The year 1963 was a crucial one for King. Many recall the August 1963 March on Washington, which begat King’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech, as the defining moment of the civil rights movement. But the setting for the year’s most crucial action was not Washington, D.C., but Birmingham, Alabama.

Birmingham was a place described by King as “the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States.” It was a city where not only were libraries segregated, but books containing images of black rabbits and white rabbits on the same page were banned from the shelves. It was a city where, according to a famous report by New York Times correspondent Harrison Salisbury, “every medium of mutual interest, every reasoned approach, every inch of middle ground has been fragmented by the emotional dynamite of racism.” It was a city where bullets, bombs and burning crosses served as constant deterrents to African Americans who aspired to anything greater than their assigned station. There, during the spring of 1963, King and his associates in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference staged a nonviolent campaign that transformed America.

The campaign, which was aimed at desegregating the city’s businesses and public facilities, started with a whimper but would find its legs weeks later when elementary and high-school students were recruited to participate in the demonstrations. It is the iconic images of those children and teens marching against the brutal assaults of Birmingham public safety commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor’s fire hoses and police dogs that stunned the nation and led to the eventual dismantling of the Deep South’s elaborate system of apartheid.

Rieder weaves this history in and out of his narrative, reminding us at every turn just how fragile and human the desegregation effort was from the outset. On April 12, 1963—Good Friday—King was arrested for demonstrating on the streets of Birmingham. He spent eight days in solitary confinement. Meanwhile, the movement threatened to implode from the weight of internal and external forces—an initially unfocused strategy, infighting among the leadership, a Kennedy administration beholden to the votes of segregationist Democrats, and conservative black businessmen uneasy about the public protests.

King was slipped a copy of the local newspaper in which he spotted a “Call to Unity” from a group of prominent, socially moderate Birmingham ministers. The group—composed of six Protestant ministers, a Catholic bishop and a Jewish rabbi—was supportive of civil rights for Negroes but critical of King’s “extreme” protest methods, which the clergymen felt would lead to civil unrest and unnecessary violence. They referred to King as an “outsider” and criticized the movement for “unwise and untimely” demonstrations.

This attack both hurt and infuriated King. Scrawling feverishly in the margins of the newspaper and on any other paper scraps he could obtain, King fired off an almost stream-of-consciousness rebuttal of the clergymen’s statement. His scribblings were gradually smuggled out of the jail by an aide and later edited into a cohesive whole under the supervision of King’s SCLC colleague Wyatt Tee Walker.

Gospel of Freedom takes its title and momentum from King’s words in the letter’s introduction defending his presence in Birmingham: “Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their ‘thus saith the Lord’ far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom far beyond my own hometown. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.”

Rieder traces the letter’s rhetorical flow from King’s initial attempt to “win over his critics through appeals to their reason, sympathy, and conscience” to its sudden midpoint shift to a more blunt and indignant tone. “King drops the mask,” says Rieder. “Instead of explaining himself, he chides and criticizes. He shows himself to be not just a black man but an angry black man. The diplomat gives way to the prophet.”

In a post–civil rights era that over time has steadily tamed and sanitized King’s radical opposition to social injustice, Rieder boldly hoists before us a more nearly complete Martin Luther King Jr. whose profound appeals to nonviolence were balanced by equally aggressive calls to resist the spiritual corruption and institutionalized racism of American society and, when necessary, its resultant laws. The author’s previous book on King, The Word of the Lord Is Upon Me, provided a similarly insightful contribution to MLK scholarship, offering an unvarnished meditation on King’s several voices—his black Baptist voice, his community organizer voice and his “white” crossover voice. That book revealed King the bawdy jokester, King the angry prophet—and above all King the devout black churchman. Gospel of Freedom revives and deepens that approach, examining “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as both King’s formal public response to white moderate critics as well as an intimate, “transcribed form of oral culture” for his black allies.

Rieder examines the letter’s importance on political, spiritual and literary grounds, but he also recognizes the document’s origins as a device for propaganda. Indeed, the idea of creating a prison epistle as a kind of press release for the movement had been floated during one of King’s earlier jail stints but was nixed. While this speaks to the fact that there always had been a PR motive in mind, Rieder’s analysis leaves no question that he views the actual writing of the Birmingham letter as King’s impassioned, real-time reaction to the eight clergymen’s public censure of his message.

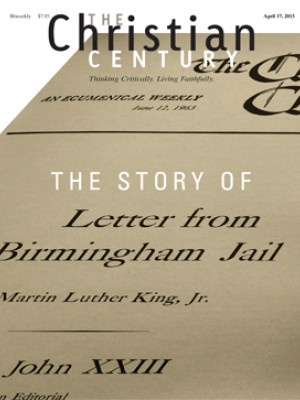

Though “Letter from Birmingham Jail” did not play a role in resolving the immediate conflict in Birmingham, it would “spread beyond the events that spawned it” and earn comparisons to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and Émile Zola’s “J’Accuse.” Weeks after the Birmingham campaign, condensed versions of King’s missive found their way to the public in publications such as the New York Post and Reinhold Niebuhr’s Christianity and Crisis journal. But it was not until the June 12, 1963, issue of the Christian Century that the complete letter was printed—along with an invitation for readers to send checks to support the work of the SCLC. Perhaps sensing the historic nature of their gesture, the editors wrote: “Believing that the document expresses, better than any other we have seen, the quality of mind and spirit which informs the most important movement for integration in the south, we . . . publish it as a contribution to justice in race relations and in the faith that it will help heal a most grievous wound which this nation is inflicting upon herself.”

In an allegedly postracial America, we have yet to fully heal those self-inflicted wounds. The election of a black president and a keener awareness of the systemic injustices facing people of color have not necessarily addressed the spiritual component of our dysfunction. But, as Rieder makes clear, the King who wrote “Letter from Birmingham Jail” was under no illusion that America was “a providential nation whose destiny was freedom.” He knew that it would require a dogged, ongoing commitment to the gospel of freedom in order for “all God’s children” to be at peace with one another.