The lure of Mormon romance

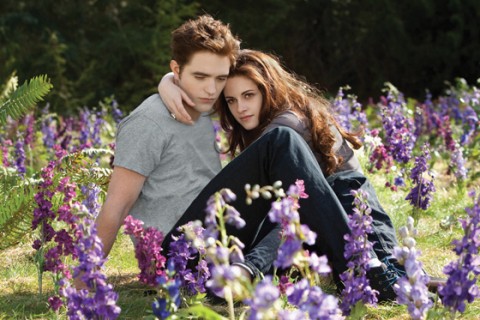

The fifth and final movie installment of the Twilight Saga, Breaking Dawn, Part 2, closes the circle on a seven-year obsession with Bella Swan and her journey toward immortal life and eternal love. In case you haven’t caught up on the series, which is based on the young adult romance books by Stephenie Meyer, let me bring you up to speed.

Bella Swan, clumsy, awkward and inward, meets and falls for the impossibly beautiful, graceful and broody Edward Cullen, who turns out to be not only a vampire but a rare breed of vampire who masters his lust for human blood and subsists on animal blood alone. Their love is instantaneous and all-consuming, and it takes Bella only a few months to decide she wants to become a vampire herself to be with Edward forever. Through a strange game of lovers’ bargaining—she wants to have sex while she is still a human, he wants to marry her first—Bella conceives a half-human, half-vampire child and almost dies in childbirth. In her death throes, Edward turns her into a vampire, and their forever after is secured.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A lot has been made about Meyer’s Mormonism in trying to explain the appeal of this abstinence-only-themed girl-meets-vampire romance. I think the better marker of Meyer’s Mormonism is the subtle way she tweaks the standard happily ever after of teen romance. Maybe I’m influenced by having read the Twilight series at the same time I was watching the HBO drama Big Love (2006–2011), which is about a fundamentalist Mormon family that practices plural marriage while trying to blend into suburbia.

The Henricksons of Big Love (comprising one husband, three wives and eight children) are not mainstream Mormons (the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints repudiated plural marriage in 1890), but they share with Saints like Meyer the doctrine of eternal marriage. Mormons believe that marriages sealed by a proper priesthood authority will continue for eternity and that these eternal marriages are required in order to reach the highest levels of celestial bliss. Marriages and the children that marriages produce are also integral to the work of salvation. In the long Christian debate about the capacity of humans to earn their salvation, Mormons come out firmly on the side of human agency. By struggling to stay on the path set by a loving heavenly father, one can earn celestial, eternal happiness. One’s intimate relationships support one on this path, provide daily opportunities for moral fortitude and are the reward for the moral battle well fought.

The Henricksons of Big Love (comprising one husband, three wives and eight children) are not mainstream Mormons (the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints repudiated plural marriage in 1890), but they share with Saints like Meyer the doctrine of eternal marriage. Mormons believe that marriages sealed by a proper priesthood authority will continue for eternity and that these eternal marriages are required in order to reach the highest levels of celestial bliss. Marriages and the children that marriages produce are also integral to the work of salvation. In the long Christian debate about the capacity of humans to earn their salvation, Mormons come out firmly on the side of human agency. By struggling to stay on the path set by a loving heavenly father, one can earn celestial, eternal happiness. One’s intimate relationships support one on this path, provide daily opportunities for moral fortitude and are the reward for the moral battle well fought.

Vampires have served as metaphors for many things, but Meyer might be the first to see their potential to be part of an allegory about the sanctified immortal life. If you want to create a fantasy about the rewards of abstinence and the beauty of eternal marriage, using vampires as immortal beings who earn beatitude through moral self-restraint is a jackpot. The defining feature of Meyer’s vampires is not their relative bloodlessness but their constant struggle against their persistent desire to drink human blood. Bella prepares for mastering her bloodlust as a vampire by learning self-control over her selfish desires as a human adolescent. The payoff of such moral struggle is enormous: immortal youth, superhuman strength, speed, grace, beauty and the rapturous love of her teenage sweetheart for all eternity.

The Henricksons are also striving for celestial bliss, but their path to righteousness is cluttered with their own fears, hypocrisies, jealousies, machinations and rebellions. After watching a few seasons of their backbiting, lying and scheming, one has to wonder why anyone would want to be married to these people for all eternity. Yet there is something compelling about watching the Henricksons wrestle against their worst impulses and move toward something like unconditional love for each other. Maybe that is what makes the hope of eternal life earned through earthly love so intriguing: you don’t have to worry about where to direct your moral and spiritual energy, just turn to those closest to you and get about loving them.

The Twilight Saga and Big Love explore something that our standard romantic dramas have forgotten: the pleasures of moral struggle for the sake of spiritual growth. Big Love takes all the assumed conventions of a show like Desperate Housewives—marriage is a trap and suburbia is a pit of snakes that will suck the life out of you—and invests them with an almost fanatic possibility for holiness. It is here, in the pit of snakes, that you work out your eternal salvation. As for the Twilight Saga, the moral athleticism of its characters provides a stark contrast to the knowing cool of so many teenage fantasies or shows like Gossip Girl or the new 90210.

The difference between Big Love and the Twilight Saga is primarily the difference between adult and teenage fiction. In the former, the relationship between our deepest beliefs and motivations, much less our actions, is not so clear. Even if we know what we are aiming for, a dozen other desires, fears and contingencies press against our best intentions, perverting our progress and obscuring our self-deceit. Which is perhaps why all of us, not just those who are banking on righteousness through eternal love, need the teenage fantasy from time to time: the sweet triumph that comes from choosing good in the face of temptation and the pleasure in the promise of some final rest in which consummation will not disappoint us by producing some new aching desire.