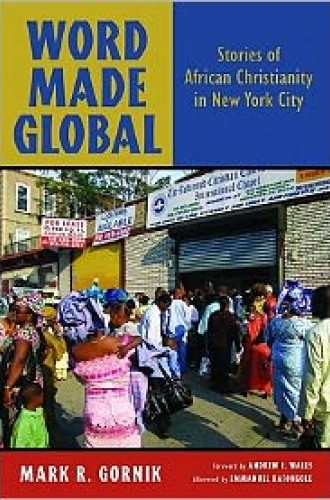

Word Made Global, by Mark R. Gornik

Over ten years ago Andrew Walls, the renowned historian and mission theologian, with whom I was studying at Princeton Theological Seminary, mentioned that one of his students had begun researching African immigrant churches in New York City. The student, according to Walls, was literally walking block by block in the city looking for these churches, of which very little was known at the time. Mark Gornik, I later learned, was that student. Word Made Global presents wonderful insights based on his ten years of painstaking and brilliant ethnographic research.

Gornik, the director of City Seminary in New York and the founding pastor (now emeritus) of New Song Community Church in Baltimore, explores the Christian movements in Africa that have crossed over into New York City and are putting down roots there. Embedded in this larger narrative are stories of African immigrants who, despite the strain and stress of living in New York, strive to live by Christian beliefs and practices that they also passionately propagate.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

By Gornik's count, African immigrants have established about 150 congregations in New York City. These are diverse in size, country of origin, membership, theological beliefs and religious practices. Several of them, Gornik notes, have no permanent place of worship and meet in rented storefronts, "converted basements" and "borrowed sanctuaries." To help the reader appreciate the wide variety of these African churches, he gives us a panoramic view of Ethiopian Orthodox, Catholic, Pentecostal, independent, francophone and Liberian congregations located in all of New York City's five boroughs. Gornik also reveals the complex local and global networks that exist among these churches, their home denominations and countries, and many Pentecostal and charismatic movements within and outside the United States.

The book reveals the African churches' bottom-up approaches to mission, as compared with the top-down approaches of many Western Christian missions to Africa and Asia. Unlike Western missions to Africa, which are often initiated and supported financially by home churches and mission boards, the African congregations are in many cases formed by individuals who migrated to the U.S. for personal reasons, often to seek better economic opportunities.

Marie Cooper and Nimi Wariboko are the founding pastors of two of the congregations Gornik describes. Cooper, affectionately called Mother Cooper, migrated to the United States from Liberia in 1984. In addition to essential personal items, she brought with her religious paraphernalia—her Bible, white cloth garments and a small wooden cross—and, of course, her Christian beliefs. Initially she worshiped with an African-American congregation, but soon she became disenchanted with its worship style. She then began prayer meetings in her apartment. Over a decade, this prayer group grew in size until it became an official branch of the Church of the Lord (Aladura).

Nimi Wariboko left his lucrative Wall Street investment banking job in 1998 to begin a branch of the Redeemed Christian Church of God in Brooklyn. He supported the nascent ministry with proceeds from the sale of his car and funds from his retirement savings.

The growing presence of African Christianity in the United States is part of a trend of Christianities of the Global South making inroads in the North. Since the 1970s large numbers of Africans have migrated to several European countries, Canada and the United States. In many cities and towns they are reviving Christianity through the establishment of new churches and evangelistic ministries. However, in the United States this phenomenon has only begun to gain the attention of academics.

Some scholars who have told the story characterize African congregations as exotic sects or, at best, ethnic churches whose central purpose is to maintain and promote the cultural practices and ethnic identity of their members rather than to contribute to the revival of Christianity in the West and North. Gornik challenges this kind of scholarship and refocuses the discussion. Through in-depth interviews, participant observation and copious photographs, he has assembled a comprehensive picture of what he considers to be the face of post-Western Christianity. Gornik wants the reader to see these African churches as evidence of African Christian mission to the United States and the Western world.

To make his case, Gornik draws the reader into a detailed and delightful ethnographic description and analysis of three African churches—the Presbyterian Church of Ghana in New York, located in Harlem; the Church of the Lord (Aladura), in the Bronx; and the Redeemed Christian Church of God, International Chapel, in Brooklyn. All three congregations have roots in West Africa. Obviously, a more representative sampling would have included churches that originated in other parts of Africa.

These churches are representative of three different streams of African Christianity. The Presbyterian Church of Ghana traces its roots to the 19th-century Basel missionary enterprise in Ghana; the Church of the Lord (Aladura) is part of the African Independent Church movement; and the Redeemed Christian Church of God is a Pentecostal congregation. Although the churches have different beliefs, practices and membership, they share many commonalities. Common to all three are a holistic understanding of salvation and a strong belief in the Bible, in the power of the Holy Spirit and in the power of Christ over evil forces.

Gornik does well to highlight the continuities between Christianity on the African continent and among the churches in New York. However, he fails to show adequately the discontinuities between them. Throughout the book he calls the churches in New York African churches instead of African immigrant churches—the term used by many other scholars. This may reflect an attempt to avoid the idea of transience and foreignness associated with the latter designation. However, it erroneously suggests that churches formed by African immigrants in New York are necessarily the same as or similar to those in Africa, in organization, beliefs and practices.

Word Made Global teaches Westerners several important lessons. First, the story and stories of African churches in New York are part of the larger Christian story of God's incarnation. As Lamin Sanneh has argued, the incarnation opens up possibilities for translations. Translations, in turn, lead to diversity. African Christianity is another translation of the incarnation story.

Second, the book reminds us that New York City is not a spiritual desert. African churches, Gornik says, are helping to transform New York into a "charismatic city, not a secular city."

Finally, the presence, beliefs and practices of African churches provide Western Christianity another opportunity to reexamine its own beliefs and practices—particularly as they relate to the reading and interpretation of scripture and to openness to the power of the Holy Spirit—and its relationship with other Christianities.