Playtime

Anyone who has watched children play knows the spectacularly creative and subversive ways in which they can use playthings, even "safe" religious ones. The Mennonite kid uses the sweet, puffy figures of the crèche set to stage a bone-crushing, manger-side brawl. The Muslim girl undresses her modestly clothed Fulla doll—marketed as an anti-Barbie and the "moral Muslim choice" for young girls—and lays her on top of a naked boyfriend doll. Many parents have intervened in the make-believe rumble or lovemaking, or wondered whether they should, or at least found it imperative to call the child for dinner.

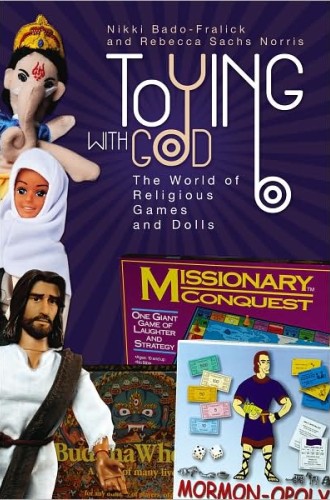

That's the problem with religious toys, say the authors of Toying with God, a study of religious toys, games and dolls and their connections to commerce, culture, gender, play and ritual. Adults create them to instill values or to pass on traditions—or just to make some money—but once the toys are in the hands of children, there's no telling what will happen. Children are not simply "passive consumers," the authors write. "They are capable of producing meanings of their own—meanings that may surprise, challenge and even undermine the goals of both marketing and parents."

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

And that's a good thing, Nikki Bado-Fralick and Rebecca Sachs Norris would say. Professors of religious studies at Iowa State University and Merrimack College, respectively, Bado-Fralick and Norris roundly criticize idealized religious play such as that portrayed on the website of one Christian toy manufacturer: Dad is reading the David and Goliath story from the Bible, and Mom is holding a talking David doll. Mom then asks, "How do you think that David answered Goliath? Let's push the button and find out what happens next." "There is still some question of whether play is still play when it is imposed by adults with didactic, edifying, or moralizing aims," the authors write. "Religion can embrace fun, but can fun withstand control?"

Not all religious toys and games are created for children, of course, and some are designed as satire instead of earnest religious statements (think bobblehead Jesus, for instance). The authors investigate a diverse array of toys: board games like Missionary Conquest and The Richest Christian (in which one card reads: "You have the opportunity to be a missionary to an uncivilized tribe. If you do, the natives there steal your clothes and dishes and you must pay $1,000 to replace the necessities. Receive 40,000 Eternal Treasures"), lunch boxes emblazoned with Krishna and Kali, Lookin' Good for Jesus makeup compacts, and Christian tarot cards.

The authors explore ritual divination and the ancient use of dolls for religious and magical purposes, the connection between advertising and evangelism, the almost religious dedication of pop culture to "having fun," and the resulting corporate appropriation of fun in mandated "funtivities." And they consider the reasons that the Abrahamic faiths seem less accommodating of play and fun than other religious traditions.

Surprisingly, given the outrageous nature of some of the artifacts they examine, the authors resist an easy critique of the way in which religious games and toys wed religion with commerce. Such an argument tends to idealize a religion of the past that was presumably untainted, uncommodified or at least mercifully free of chubby Jesus dolls and Salvation Candy Tubes. But "organized religion and money have always been intertwined," Bado-Fralick and Norris point out. (Indulgences in the Middle Ages come to mind.) "It is not the relationship between religion and money that is the problem, but rather the relationship between religion and a consumerism perceived as wildly out of control—buying and having as a way of life—that unsettles many of us."

They outline several of those unsettling aspects in their playfully titled chapter "Holy Commerce, Batman!" and admit to being unsettled themselves. They explore the irony that toys meant to instruct children in Christian ethics are produced in China, known for its exploitation of poor workers, as well

as the ecological problem of mass-produced religious toys that will live out their eternal plastic destiny in landfills across the globe. The authors also mourn the unmooring of religious symbols from their communities and meanings in an increasingly commodified marketplace. When Zen alarm clocks are sold at Wal-Mart and Mayan temples are water park themes, it's hard not to wonder whether the incessant hum of commerce has begun to render religious tongues incoherent.

These are separate questions, of course, from the one about whether the use of religious signs in toys and games is sacrilegious. This was the concern voiced by my Catholic doctor, who, upon seeing the book I was reading, told me about her sister-in-law's propensity for buying her children chocolate crosses at Easter. "I just can't bring myself to eat one of those," she said, her mouth puckering in distaste.

I tend to agree, although I'm certain that for some people the foil-wrapped chocolate cross or resurrection-themed beach towel serves as a profound reminder of the paschal mystery. It's easier to scorn these material manifestations of contemporary religion, whether on grounds of sacrilege, commodification or simple aesthetic awfulness, than to look carefully at what these items reveal about humans and our desire for a tangible sign of the sacred.

One of the book's most interesting chapters deals with the connections between play and ritual: the play inherent in religious ritual and the rituals performed in play. Both play and ritual "share in the power of transformation, that ability to imagine and act 'as if,' creatively to hold multiple meanings and multiple identities at the same time," the authors write. And just as play can be dangerous because of its subversive potential—remember the crèche battle and doll intercourse—so too, the authors say, can ritual. My cousin, recently ordained by lot, would testify to the risky nature of choosing a Bible that may hold a slip of paper indicating that you're now a minister for life. More common religious rituals also share characteristics of play: the abandon of a Pentecostal worship service, the costuming of a priest, the theater-like rites of Purim.

By the end of the book, readers may be a little weary of the authors' repeated defense of their project. Western scholarship has ignored religious toys as artifacts worthy of study, they say, perhaps a few too many times. High religious rituals, systematic theology and exegesis, and text-based practices have been privileged items of study, they claim, while religious toys and games and other material aspects of religion have been considered too trivial to study seriously. I do not doubt that this is true. Yet when writers repeatedly excoriate others for not having studied what they do, I sometimes wish they would admit to feeling relief that other scholars' oversights created their research niche.

But to criticize the authors for making a case that their work is important is probably mere fussiness. Their work is important, in part because they manage to maintain an irenic and nonelitist voice in the face of Wash Your Sins Away bubble bath and Angel Wars superheroes. It takes a lot of restraint to write about the world of "religiotainment" without a supercilious smirk. "Religious games and dolls evoke the transformative power of ritual," the authors write, and although they are not as significant a force in the life of the believer as regular rituals such as worship, "they should not be underestimated."

Perhaps many makers of religious toys and games and dolls, for all their sullied profit motives and their use of plastic, are truly seeking to reincarnate a sometimes abstract word. Incarnation may be what children at play are after as well, even with their lively animations of crèche figures and Fulla dolls. Both play and religious ritual allow us to act "as if," the authors remind us, just "as when the morning's fresh-baked bread becomes the holy body of Christ." And given humanity's finite and fallen nature, acting "as if" might come as close to living the faith as we can get.