American beginnings

Terrence Malick’s The New World is not your father’s historical adventure film. Though purported to be an epic treatment of the founding of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, complete with Indian attacks and the heated love affair between Captain John Smith (Irish actor Colin Farrell) and the Indian princess Pocahontas (newcomer Q’orianka Kilcher), such elements form little more than a gilded frame for the picture that Malick puts on display.

For three decades the elusive Malick has been cinema’s equivalent of J. D. Salinger. Though he has made only four films in 32 years and never sits for photos or interviews, he has been idolized by two generations of filmmakers, dating back to his startling 1973 debut film Badlands. Malick was rumored to be contemplating a film version of the book of Genesis.

In Malick’s vision, Eden appears as the New World—a sublime place of nobility and tranquility that is quickly despoiled with the arrival of the English. Though these brave but somber Englishmen seek freedoms of their own, once they realize there is lots of money to be made planting tobacco, they use their superior firepower to start pushing the Indians westward.

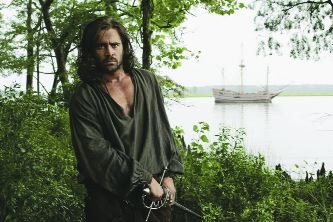

But that’s a later part of the tale. Malick seeks to show how the whole conflict began, using the relationship between Smith and Pocahontas as a prism. Smith arrives in Virginia in chains, sentenced to be hanged for insubordination. He is spared by Captain Newport (Christopher Plummer), who can’t afford to kill off any able-bodied men. Smith meets Pocahontas, daughter of the great Chief Powhatan. She is a curious sprite (her name means “playful one”) who seems fascinated with Smith’s long dark hair and thick black eyebrows.

Trusting that we have our primary school memories of the story, Malick skips over much of the exposition. (Who are these white adventurers? Why did they come? What do they want?) Employing the lush photography of famed Mexican cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (who shot much of the film in 65 mm), Malick looks at the New World from nature’s point of view. Everything from the camera angles and costumes to makeup and production design conveys how difficult it was for the Jamestown colonists to survive. They came within a single battle of being killed off.

Pocahontas’s role in the story is quite different from the one we are familiar with. True, she falls for Smith. But in saving the white men by warning them of a sneak attack, she guarantees the death of her brother and seals the fate of her tribe. This betrayal forces the hand of her father, who banishes her forever, leading to her eventual journey to England, where she died.

But even this key plot point plays second banana to Malick’s impressionistic telling. His trademark use of voice-over (shared by three characters) doesn’t explain the story or character motivations as much as it creates a mood, asks questions and expresses confusion, longing and fear.

The film was shot with natural light (as was Malick’s memorable Days of Heaven) so we can more closely feel the chill of dawn, the gloom of dusk and the sting of icy snow pelting the faces of the settlers. In true Malick style, instead of showing entire bodies moving down a road or wading a river, he treats us to a stray hand, a random boot, a shadow on the ground or a shot from underwater. This may be disconcerting for those accustomed to narrative-driven storytelling, but it’s a breath of fresh air for those who appreciate moviemaking art.

Malick’s love story is driven by a poetic vision, and it is focused less on romantic entanglements than on pain and obsession. It suggests that things might have been better for all if the English had never entered the garden.