The isolation of Wallace Stevens

A new biography reveals the poet’s devotion to his vocation. It also reveals his loneliness.

Readers familiar with the poet Wallace Stevens (1879–1955) might know “Sunday Morning,” an early poem that rejects biblical faith in favor of “divinity within,” or “High-Toned Old Christian Woman,” which places poetry above faith as the “supreme fiction.” Others might know that when Stevens cleaned out his childhood home in Reading, Pennsylvania, he threw out his Sunday school Bible, reporting later that he was happy to have the silly thing out of the house.

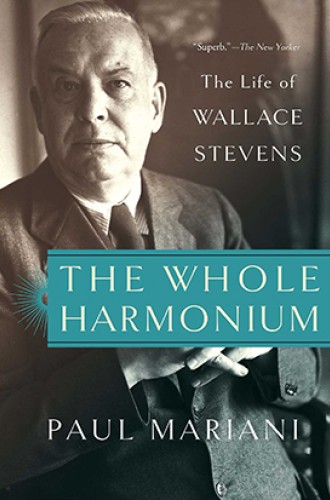

Biographer and poet Paul Mariani sets these pieces and the rest of Stevens’s substantial body of work into a thick and valuable biographical context. Thoroughly researched, carefully documented, and held together with cogent commentary and lyrical descriptions of the poems, the book does justice to Stevens’s achievement and fills out his singular and somewhat secret vocation as a poet.

To his neighbors in Hartford, Connecticut, Stevens was a Harvard-educated, New York–trained corporate lawyer and insurance executive. But he is remembered today for his achievement as a modernist poet. Mariani places Stevens “among the most important poets of the twentieth and the still-young twenty-first century, sharing a place . . . with Rilke, Yeats and Neruda.” Christian readers have reason to grapple with Stevens not only for the chime and luster of his abstract poems but also for his lifelong, disciplined dedication to the vocation of poetry, the intensity and aim of which might be compared to that of a biblical prophet.