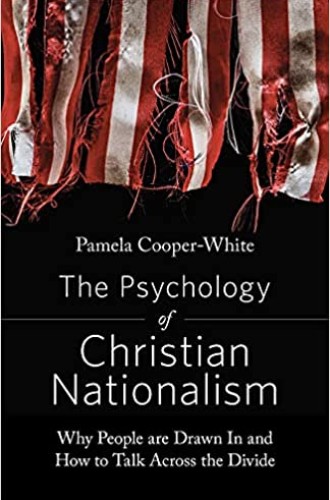

What Christian nationalism is and what to do about it

Pamela Cooper-White details best practices for difficult conversations that privilege listening, reflexivity, curiosity, and care.

Pamela Cooper-White, an Episcopal priest, pastoral psychotherapist, and professor at Union Theological Seminary, is known for research and writing that navigates the fraught intersections of theology, psychotherapy, and social justice with courage and care. Her work is deeply rooted in the psychoanalytic tradition but decidedly not root-bound, as her earlier writings on relational psychology and multiplicity demonstrate (Braided Selves); nor is she reluctant to bring psychoanalytic sensibilities to bear on systemic evils, such as violence against women (The Cry of Tamar; Gender, Violence, and Justice) and the antisemitic impulses at the origins of psychoanalysis itself (Old and Dirty Gods).

In her new book, Cooper-White continues her practice of theoretically informed truth telling in the face of some of the most confounding and complicated maladies of our present moment: the polarization of American society and the dangerous ascendancy of Christian nationalism. Readers who want to look away from the disease that is currently ravaging our body politic, those seeking a diverting beach read or a soothing affirmation of their own biases, will do well to choose a different companion.

The book’s slim profile—only three chapters and less than 200 pages—belies its range and intensity. In the opening chapter, the author packs a mere 30 pages with an unflinching social analysis of the “unholy alliances” that have joined forces in our present moment. She assembles a hard-hitting account of Christian nationalism that begins with narratives of the January 6 attack on the Capitol building and the prominence of Christian symbols there; presents data from large-scale statistical studies of social attitudes and beliefs by sociologists of religion to identify the tenets of Christian nationalism and its adherents; traces the heritage of the movement in books and articles by pastors identified with Christian nationalism as well as those of their historical evangelical forbears; and points to broader social injustices that have fueled the movement’s popularity such as racism, xenophobia, classism, and sexism.