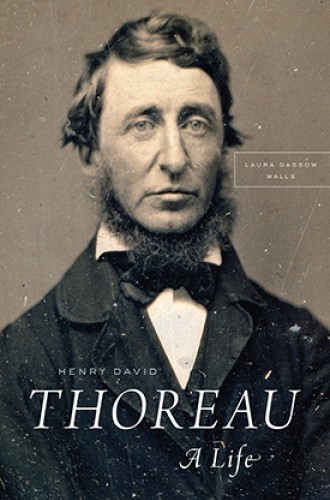

The vocation of Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau's beautiful writing, biographer Laura Dassow Walls shows, is scripture waiting to be heard.

Henry David Thoreau is often celebrated as the man who turned his back on society, returning to nature to become a citizen of the wilderness. Thoreau, in this view, becomes a hermit who shuns his neighbors in Concord, Massachusetts, greeting woodchucks, mice, and turkeys as his new neighbors. But Laura Dassow Walls, who teaches English at Notre Dame, points out that Thoreau was hardly a recluse: he met his neighbors every day on his walks. With colorful and rich details of Thoreau’s childhood, youth, and adulthood, Walls draws a stunningly vivid portrait of Thoreau as a man who, even as a child, believed that to be a writer was his highest calling.

In 1837, the young Thoreau records an incident in his journal. He recalls playing Indians with his brother, John, and unearthing an arrowhead. As he rubs the arrowhead, he feels as if he were holding a live object handed to him by a Native American elder. The barriers between past and present, living and dead break down in that moment. Once Thoreau commits this memory to his journal, he makes the incident true, observes Walls. In this act, he “takes up the writer’s double consciousness . . . opening up a double vision: past and present, white and Indian, civil and wild, man and nature.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

At Harvard, Thoreau embarks on his vocation of writing by keeping a commonplace book, copying extracts from his reading. After his graduation, Thoreau celebrates his birth as a writer. His friend Ralph Waldo Emerson calls on Thoreau to “see how the inexhaustible waters of life roll through the catch of every moment.” Thoreau responds by inaugurating what Walls calls “a monumental life’s work, an epic journey of over two million words, sustained as long as he could hold a pen.”

Thoreau is never without his pencil to scribble down his observations, and no aspect of nature, history, or society escapes his gaze. Walking becomes synonymous with writing for Thoreau, the measure of his steps that of his prose. As Walls points out, “he made of his life an extended form of composition, a kind of open, living book.” Thoreau deliberately wants his own journals of his travels—A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers—to flow organically like the rivers themselves, to be a living book rather than a book of self-contained essays like Emerson’s.

When Thoreau goes to Walden Pond in 1845 for his now-famous stay of two years, two months, and one day, he aims to “claim an entire life, and declare that writing would not be an occasional hobby but the central hub of his whole being.” His declaration to live deliberately and to meet the facts of life face to face, Walls says, has “the force of a vow, a sacred commitment to confront.” Thoreau’s every act, as well as his surroundings, reflect his vocation. “His purpose was profoundly religious. His house was ‘a temple . . . made of white pine’ . . . [and] eating would be a sacred act, ‘a sacrament . . . sitting at the communion table of the world.’” Thoreau’s writing is scripture waiting to be heard.

At the bicentennial of Thoreau’s birth, it’s worth asking: Which of his writings most characterize him? Many readers continue to separate the Thoreau of Walden from the Thoreau of “Civil Disobedience,” the naturalist from the political thinker. But Walls brilliantly shows that his activism and his love of nature spring from the same roots. Thoreau saw society in nature and nature in society. Whether he was writing about John Brown and pleading for Brown’s innocence or about wild apples or the dispersal of seeds, he could see the connections between the nonhuman and the human. The ethical vision he developed in “Resistance to Civil Government” becomes, according to Walls, the foundation of both his political philosophy and his environmental ethics.

Walls accomplishes powerfully what every biographer hopes to accomplish. She draws enough of a family portrait to set Thoreau in his context—his father became a prosperous maker of pencils, and Thoreau worked in the family business. She paints even more colorfully a picture of the rapidly changing society whose air Thoreau breathed. Drawing deeply on his journals, letters, and writings, Walls guides us through them, gently driving us back to their fierce beauty, their humane soul, and their gleaming insights. Thoreau emerges from the compulsively readable pages of Walls’s biography as a true American original.