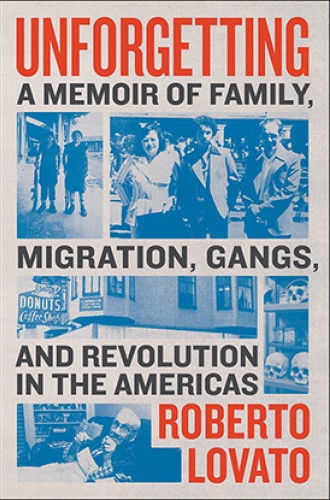

A US son of Salvadoran parents explores his complex identity

Roberto Lovato’s harrowing memoir is a process of personal and collective unveiling.

While studying philosophy in college, Roberto Lovato became fascinated with the ancient Greek concept of aletheia, which is often translated as “truth” but more directly means “uncovering” or “unveiling.” Lovato’s harrowing memoir is a process of personal and collective unveiling.

As a US citizen born to Salvadoran parents, Lovato undertakes a journey of “unforgetting” that leads him to unveil painful realities about his parents’ and grandparents’ complex identities as both perpetrators and victims of violence. Spanning nearly a century, Lovato’s family history is linked to that of two nations, El Salvador and the United States, bound together in an asymmetric relationship of economic and military imperialism.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

One of the book’s two epigraphs is from Ernest Renan’s “What Is a Nation?” It states, “Historical inquiry, in effect, throws light on the violent acts that have taken place at the origin of every political formation, even those that have been the most benevolent in their consequences. Unity is always brutally established.” Seeking to reckon with this violence in both his personal background and the wider political context of the relationship between the United States and El Salvador, Lovato’s narrative shifts between three time frames.

First, he explores his father’s childhood in the 1930s, when El Salvador’s government perpetrated a massacre against 30,000 indigenous people who dared to protest wealthy landowners’ exploitation of them—an event that Anders Sandberg of the University of Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute has described as the single most violent event of the modern era. Lovato then moves on to the early 1990s, when he traveled to El Salvador to aid the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front near the end of the country’s civil war. Finally, he jumps forward to 2015, when he returned to El Salvador as a journalist to document gang violence.

Through this exquisitely braided narrative, Lovato uncovers unsettling links between militarized police in the United States and death squads in El Salvador, between US state violence against immigrants and the policies that drive migration in the first place, between mass graves in El Salvador and mass graves in the Arizona desert, between a cash-crop economy established around coffee in the early 20th century and the drug war of today.

However, Lovato’s story is as much one of love, friendship, and familial unity as it is of violence. More than once in the text, Lovato references Joan Didion’s oft-quoted statement, “Terror is the given of the place,” which she wrote in her book Salvador after a two-week visit to the country. For Lovato, it is a huge problem that Salvadoran stories have been told principally by White, North American visitors to the land.

“I was born there,” says Lovato’s student Elizabeth. “I remember seeing dead bodies and things that cause terror . . . but I also remember eating jocotes, always having lots of family around, and playing escondelero in the cool shade at the foot of the volcán ’til late. I remember a lot more than ‘terror,’” she says. But then she references the US government’s provision of finances and weapons to El Salvador during the Salvadoran civil war. “And who paid for that terror?” The United States. “That’s who.”

A big part of Lovato’s story is his recognition of his own diasporic identity as both a Salvadoran and a US American. As a young boy visiting El Salvador with his parents in 1975, he is shocked and insulted when some of his cousins criticize US military policy. As a young adult, educated about the US history of economic and military imperialism in El Salvador, he is filled with rage at his birth country. “I arrived at a difficult but necessary conclusion: I would stop using the word American to describe myself—or anyone else. I would use the word only in quotations or with an accented e to refer to the continent of América.” It is only after learning of his own family’s past that he is able to reconcile himself to the complexities of his identity.

Like many Christians, my first encounter with El Salvador’s history was through the story of St. Óscar Romero, that fearless, faithful advocate for justice who was killed by US-trained assassins in 1980. This story marked me so profoundly as to inspire me to become fluent in Spanish and pursue advanced studies in Latin American history. But I still have much to learn, and for me, this historical memoir was truly eye-opening in the ways it links the gang violence of today to the economic inequality that began in the early 20th century, when coffee became a dominant cash crop and solidified an existing gap between the rich and poor.

This memoir is also required reading for so many in the United States who are unfamiliar with the history of military intervention, particularly through such organizations as the School of the Americas (now known as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation) at Fort Benning, Georgia. To all of those well-meaning US Americans who, when faced with discussions of immigrants from Central America, ask, “Why don’t they just come here legally?,” this book might help to provide some answers.

Unforgetting reads like a gripping novel and a poignant poem of witness by a man who is both a native and an outsider to a country. As Lovato reckons with both personal and historical trauma, he manages to practice the aletheia which for him is the first step toward healing. In the words of Roque Dalton, one of El Salvador’s national poets, Lovato seeks “the almighty union of our half lives / of the half-lives of every one of us that were born half dead / in 1932.”

As a reader of this powerful story, I am encouraged by the redemptive power of unforgetting, a process that, following Lovato’s lead, I believe all US Americans should undertake. While there is much horror to be found, there is also beauty and joy. Uncovering his own family history, Lovato ultimately reaches a different conclusion than Didion about El Salvador: “Love is the given of the place.”