Traveling to find home

Tom Fate’s essays present an ethically complicated journey of discovery.

“I’m not a tourist. I’m a traveler.” I heard this claim again and again throughout my footloose early 20s, when I stayed in youth hostels in Madrid, Mendoza, Argentina, and the Uyuni salt flats in Bolivia. I heard it from bearded, sandal-shod men and paisley-skirted women, their belongings stuffed into compact backpacks. We were all hoping to discover some new knowledge or spiritual inspiration that we believed couldn’t be found at home. A tourist was the last thing any of us wanted to be.

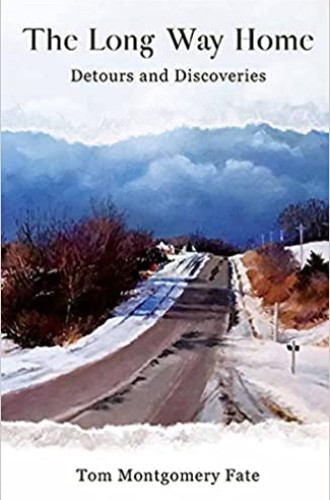

This ambivalence about travel haunts Tom Montgomery Fate’s newest book of essays. Grounded in a strong sense of place, The Long Way Home begins with an account of Fate’s upbringing in Maquoketa, Iowa, detours through his experiences traveling to Nicaragua and the Philippines during the politically charged 1980s, and then returns to various North American landscapes: the Black Hills of South Dakota, Ontario’s Quetico Provincial Park, and the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon. With curiosity and attentiveness, Fate engages in a passionate search for home: “It’s where my sense of being and my vast longings converge into one thing, something wordless—a kind of knowing, or belief, that I belong to Creation.”

The narrative starts with Fate’s idyllic childhood in rural Iowa. In “Fishing for My Father,” he describes growing up as the son of a Congregational minister and learning that his own faith is tempered by doubt. As a teenager, Fate is hesitant to get confirmed in the church and realizes that his skepticism comes, ironically, from his father, whose Sunday sermons encouraged him to question Christian teachings. “Maybe the problem is that you were the only one who was listening,” his father says, accepting his son’s departure from expectations.