There is no single refugee resettlement story

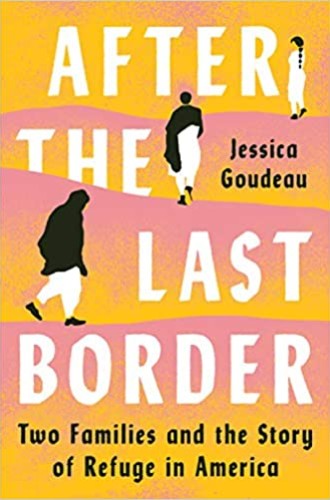

Jessica Goudeau’s new book embeds the memoirs of two very different women in a primer on what it means to seek refuge in America.

Refugee advocates often tell stories using a representative figure to evoke sympathy and motivate charity. Others argue for the restriction of refugee resettlement, using the rule of law as a reason for limiting that sympathy. Jessica Goudeau’s first book is timely and helpful because it avoids these opposing poles.

After the Last Border offers detailed narratives of two refugee experiences while intermittently pausing to explain refugee law and policy. In addition to gaining a working knowledge of what refugee resettlement entails, readers will benefit from Goudeau’s insider knowledge of that system across many years. Just as impressive is the novelistic form she uses to make these stories come alive.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The subtitle is the first clue that Goudeau is writing a different kind of narrative, one that cannot be encapsulated in a singular story. The two families profiled in the book are represented by Hasna, a Syrian grandmother who arrives in Texas in 2016, and Mu Naw, a young mother from the Karen people of Myanmar who arrives in 2007 after spending most of her life in Thai refugee camps.

Both stories are about refugee resettlement (that is, being recognized by the United Nations as an official refugee and then receiving a placement in a receiving country) rather than seeking asylum (crossing an international border and claiming protection upon arrival). By virtue of being resettled in the United States, both women represent a minority among global refugees. Both are mothers and people of faith. But this is where their similarities end.

Hasna does not want to leave home but accepts an offer of resettlement in hopes of unifying her family members who have been violently scattered by the civil war in Syria. Shortly after her arrival, America’s prioritization of family reunification is dropped and resettlement is stopped altogether. Separated now from her family, perhaps permanently, Hasna holds onto her memories. For Syrians scattered around the world, she shows, Syria still tastes like honey on the tongue.

Despite being betrayed by changing laws, Hasna can still observe that kindness must exist in a country that has developed social infrastructure for refugees. Her story is difficult to read at times, but it makes clear the purpose of refugee settlement. Its power highlights the value of stories in educational campaigns about the positive impact of resettling refugees.

Mu Naw buries love letters from her husband in the refugee camp, expecting she’ll return to her native Myanmar. On arrival in America, she realizes with grief the permanence of her move. Mu Naw’s story shows the hidden understory of refugee success. We see brief glimpses of achieving the American dream: a profitable entrepreneurship, home ownership, and a surviving marriage. But they are sandwiched by massive social and psychological barriers. The stress proves hard on Mu Naw’s marriage; a friendly volunteer turns out to be a sexual predator.

Yet she is sustained by “the unlikeliest thing—a bureaucratic program laced with goodwill and hope,” a well-resourced refugee resettlement system, and the support of extended family who migrate with them. Comparing Mu Naw to Hasna, readers can see specifically how varying national priorities have created different outcomes for the two women.

As I read these stories, which are so steeped in sensory detail and yet clearly written by an outsider to the experience, I wondered how a non-refugee author came to write this book. The afterword explains that Goudeau’s role was to interview two friends and then translate their stories for American non-refugee readers, using the writing conventions of fiction. The result is a third-person double memoir that is all the more accessible because it reads like fiction. The names of the women are changed, but their stories are real.

Goudeau’s explanation of the writing process depicts a conscientious consideration of how to handle the gift of another person’s story. Her acknowledgment of the ethical challenges she faced is a breath of fresh air within the refugee storytelling tradition.

Crucially, this book is not just about refugee experiences. It is, more precisely, about refuge—the way America imagines itself as a refuge (or not) and the impact of this self-perception on people around the world. Inserted between the alternating timelines of the two women, seven short chapters detail the history of refugee resettlement, from the aftermath of World War II, when the term refugee was coined, to 2018. Readers learn about the shifting definition of refugee, the changing political considerations that guide which refugee situations are prioritized, and the vulnerability of some populations to America’s fickle sense of identity. This larger narrative of American refugee law and policy sharpens the significance of the evocative human stories Goudeau presents.

Parallels across history emerge. For example, Goudeau explains early on how the recession of the 1930s fomented a deadly combination of racism and isolationism and led to seismic political changes. Connecting the dots, the final chapter on refugee resettlement policy references the economic recession that started in 2008 and the subsequent gutting of refugee resettlement infrastructure by the Trump administration.

The book’s critiques are not politically partisan. Every decade shows that refugee resettlement in the United States is shaped more by national identity than global need. Goudeau convincingly demonstrates that at every point the question “Who are we?” is more relevant to the reception of refugees than “Who needs protection?”

My only discontent—and it may not be fair, given the book’s already impressive sweep—is that it might have been valuable to trace a longer and broader history. A moment of miraculous international agreement did enable the UN Refugee Convention following World War II, and this promise to “never again” refuse refuge to victims of genocide is a powerful rhetorical origin point for refugee advocacy. We see in Hasna’s story, though, that only 60 years later victims of genocide are again being refused safety.

Perhaps examples of refugee protection offered in countries around the world could freshen our imaginations. Certainly, in North America, the dependence of refugee welcome on national self-interest suggests that we need a longer tradition of refuge to reference in our conversations, something deeper to protect the practice of offering refuge. For many people of faith, this will be global history told in sacred scriptures: where ancestors wander and where God offers a motherly wing as refuge for any image bearers.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “America the refuge?”