The confluence of pastoral, prophetic, and political theology animates much of the most exciting recent work in the field. How can we live faithfully in the context of social and political systems that promote white supremacy and prize financial gain over care for the common good? What does ministry mean in the context of these systematic realities? In Radical Discipleship: A Liturgical Politics of the Gospel (Fortress), Jennifer M. McBride takes on such larger questions with gusto, writing out of the conviction that lived theology involves “placing oneself in situations of social concern as one responds to Jesus’ call to follow him there.”

McBride bases her account on her 2008 postdoctoral fellowship year at Emory University, where she led the theology certificate program at a women’s prison in Atlanta, Georgia, while simultaneously participating in Atlanta’s Open Door Community, a 35-year-old intentional Christian community that works to reduce the distance between people across socioeconomic and racial lines. McBride offers an extended liturgical narrative, stretching from Advent through Pentecost, in which she reflects on the meaning of discipleship in the midst of her daily rounds. She includes an important account of mass incarceration in the United States, along with particular prisoners’ stories of their lives, their hopes, and their fears. She asks, what does the hope of Advent or the peace of Christmas mean behind bars?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Bringing her experiences of prison teaching and community life into conversation with the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King Jr., McBride defines discipleship as the embodied commitment to follow Jesus into the places where people suffer. This involves drawing near to prisoners and homeless persons, in order to reduce the social, material, and spiritual distances that poverty, racism, homelessness, and the criminal justice system impose. The day-by-day reflective tone of the writing models a kind of integrated, thoughtful faith for our times. McBride gains the courage to connect across social boundaries through her relationship to the Open Door, a spiritual community that engages in sustained and rigorous social analysis along with equally thorough theological reflection.

Relationality across boundaries is similarly a theme in Nancy J. Ramsay’s edited volume, Pastoral Theology and Care: Critical Trajectories in Theology and Practice (Wiley-Blackwell). Ramsay hosts a discussion of seven distinct trajectories within the field of pastoral theology, each written by a proponent of that approach, and each centered around a case study or a personal vignette. Together, these essays reveal the field’s movement toward understanding the communal and contextual nature of human life and the related imperative to foster holistic forms of care in and with evolving communities of faith.

Two chapters stand out for their focus on care in pluralistic, international, and intercultural settings. In an essay titled “Caring from a Distance,” Kathleen Greider uses a case study to illustrate how care can cross over vast religious, spiritual, and cultural distances. The Parents Circle-Families Forum is a group of over 600 Palestinian and Israeli families who have all lost a family member in a violent conflict. Death and grief—important topics in pastoral care—are the lens through which PCFF seeks to end violence and promote peace. The organization holds intergroup conversations addressing themes of irreparable devastation, inescapable finitude, and living and working with enemies. Greider points out that the sharing and discussions taking place here are not free of conflict, nor does mutual understanding of loss imply that the different sides have equal grievances. The validation of pain does not obliterate asymmetries of power. Greider advises that reverent curiosity, more than agreement or even meaning making, is needed for integrity in caring across borders.

Emmanuel Y. Amugi Lartey, an international scholar originally from Ghana, contributes “Postcolonializing Pastoral Theology.” His case study involves a Ghanaian couple whose daughter was mysteriously hurt in school. Was it an accident? Was she pushed? The case is complicated by the family’s diverse religious traditions, influenced by colonial movements in history. Lartey notes that care in this setting must include the entire extended family and allow each person’s voice to be heard. Postcolonial pastoral care involves building safe communities that promote the voice, health, and well-being of all persons.

Also written in a contextual and postcolonial vein is Kenyatta R. Gilbert’s Exodus Preaching: Crafting Sermons about Justice and Hope (Abingdon). This is a highly practical manual offering multiple “crafting strategies” for preaching with prophetic consciousness. Noting that “racially blind preaching can only exist in the colonized mind,” Gilbert focuses on African American prophetic preaching in its historical and cultural particularity. Exodus preaching highlights the exodus story of liberation from bondage, the Hebrew prophets’ call for justice, and the incarnational and messianic witness of Jesus Christ.

Practice and theory converge in this work: the author’s sermon-crafting strategies are informed by thoughtful theological reflection on “human tragedy and communal despair.” Gilbert reminds readers of the sociopolitical dynamics that are always at play in interpreting texts. He instructs preachers to recognize power dynamics when selecting and exegeting texts and to name the social realities of life for communities of color so that the political dimensions of the text can be fully understood in current, concrete situations. Gilbert breaks down the complex task of preaching toward moral accountability in the face of injustice into principles exemplified in the sermons of notable homileticians.

One of the most moving sermons that Gilbert excerpts is that of Howard-John Wesley, preaching at the historic Alfred Street Baptist Church immediately after George Zimmerman was found not guilty of the murder of Trayvon Martin. Reflecting on Otis Moss III’s son’s question, “Daddy, am I next?” Wesley preaches on the theme of “When the Verdict Hurts.” Gilbert shows how Wesley, rather than ignoring the personal and painful reality of racial injustice, slowly and painstakingly processes it through the sensitive words that unfold in the sermon. Gilbert emphasizes the importance of both naming the political realities that mark a community’s life and proclaiming the hope of God’s real presence in the world.

Ryan LaMothe also steps back to look at broad political realities in Care of Souls, Care of Polis: Toward a Political Pastoral Theology (Cascade). The title harks back to Larry Kent Graham’s pivotal 1992 text Care of Persons, Care of Worlds (Abingdon). Defining the polis as the organization of people living together in community, LaMothe claims that the polis should be marked by justice and care for the common good, and public policies should support people’s survival, flourishing, and liberation. If “the least of these”—those on the social and economic margins—are able to thrive, the polis can be judged as good enough.

LaMothe develops the concepts of care and justice and then shows their relationship to politics. He emphasizes that care is fundamentally relational: we are born vulnerable and dependent upon the care of others. Being human is a social and communal reality. Care is fundamental to the survival of not only individual persons and families but also larger social groups. In this he echoes Gilbert’s call to care for communities.

In detailed but highly readable prose, LaMothe argues that neoliberal capitalism and the rise of a market society privilege profit over care. He shows how this affects policies related to climate change, health care, education, and the judicial system. When greed and wealth drive policy, a politics of exclusion rather than care governs our lives, leaving some groups of people in misery and at risk of premature death. La Mothe’s compelling voice demonstrates that care for the polis is not optional but integrally related to the care of souls.

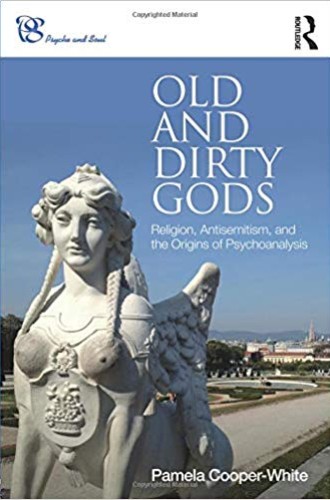

Pamela Cooper-White explores the politics of exclusion in a vastly different setting—early 20th-century Vienna—in Old and Dirty Gods: Religion, Antisemitism, and the Origins of Psychoanalysis (Routledge). Beginning with Freud’s Vienna circle in 1902, Cooper-White provides a meticulous early history of psychoanalysis and religion, offering in-depth accounts of the contributions of some of Freud’s important interlocutors, including Oskar Pfister, Theodor Reik, Otto Rank, and Sabina Spielrein. Cooper-White also narrates the pervasive if unacknowledged influence of anti-Semitism on the nascent psychoanalytic movement.

Amid the advancing dangers of the 1930s, how is it that Freud and his mostly Jewish followers in Vienna were caught unawares? Freud and his contemporaries sought to reveal underlying (unconscious) human sexual drives while denying their awareness of the racist, religious, and political repression in which they were living. Cooper-White concludes with a “plea for prophetic witness” in our times, an echo of Elie Wiesel’s warning to remember the trauma of the 20th century that was the Holocaust. As right-wing movements employ hate speech and violence in the United States and Europe while damaging discourses of racism and anti-Semitism continue to threaten and divide people, we need to pay attention. Cooper-White’s grounded and nuanced historical analysis helps us see the urgency of the political realities of our time.