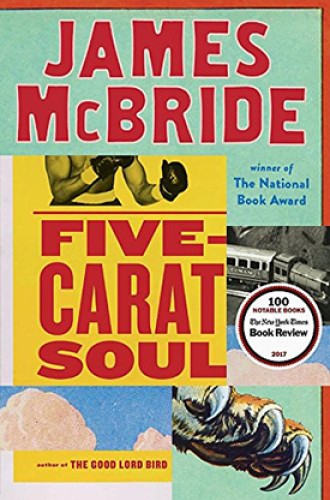

The sparkle of James McBride's stories

Five-Carat Soul is filled with hilarious storytelling, unusual characters, and stark realities.

In his 2013 National Book Award–winning novel, The Good Lord Bird, James McBride takes the outsized historical figure of abolitionist outlaw John Brown, puts the pulse of a wired fanatic in him, and sends him cavorting across the country in madcap militia attacks. The Good Lord Bird is more than an entertaining, exaggerated historical romp, however. The humor also serves to highlight the pathos and grief of the pre–Civil War violence and the horror of slavery. McBride gives us the same mix of hilarity and poignant truth in his collection of short stories, Five-Carat Soul.

In “The Under Graham Railroad Box Car Set,” a toy collector locates a one-of-a-kind train set created by gun maker Horace Smith for Robert E. Lee’s son Graham. The toy was later stolen by a slave who headed north to freedom. The collector knows that the train is worth millions of dollars in 1992, and he is ecstatic when he tracks it to its current owner, a Rev. Spurgeon Hart. As he talks to Hart’s wife on the phone, the collector realizes that he’s dealing with some unusual characters.

“Could you mention to your husband that I want to see it? ... When will he be home? ...”