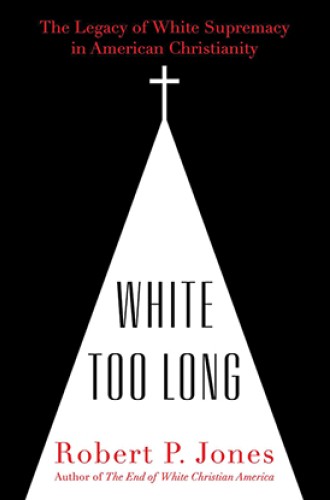

Robert P. Jones says it’s past time to reckon with Christianity’s role in White supremacy

White Too Long envisions the hope that could follow recognition and repentance.

In his 2016 book The End of White Christian America, Robert P. Jones argued that changing demographics would transform religion and politics in the United States. In his new book, Jones explores one of the greatest forces preventing an acceptance of that reality: White supremacy. White Too Long weaves together memoir, theological reflection, and careful statistical analysis to show how White supremacy has long infected American Christianity—and continues to do so.

Jones begins with a chronicle of his childhood and education in the American South, from growing up in Georgia and Mississippi to attending graduate school in Texas and Georgia. After completing his doctorate in Christian ethics, Jones founded the Public Religion Research Institute, which conducts sophisticated survey research on religion’s impact on American political attitudes.

This book’s power is in the way Jones combines self-reflective memoir with detailed social scientific analysis, demonstrating that the things he remembers are also borne out by statistics. The reality that he recalls and measures is White supremacy’s indelible imprint on churches both Protestant and Catholic, in the South and elsewhere.