Resisting as a way of life

For Kaitlin Curtice, resistance is no mere buzzword—it’s a mighty calling.

Resistance, like woke, is a word that has become misused to the point of mockery. Scroll Instagram, and you will find #resist, #resistance, and #betheresistance, the word hashtagged and diluted past its powerful meaning. It has been used to peddle a particular brand of armchair activism, something to which I am prone. (It is much easier to share a meme than to show up for a committee meeting.)

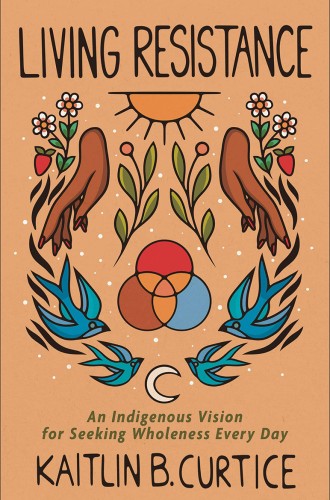

But for Kaitlin Curtice, resistance is too mighty to become a buzzword. It is “a basic human calling,” a way of living that not only fights against unjust systems but restores both ourselves and the world around us. It is “the beautiful work of wholeness-making,” and no matter your history, your heritage, or your background, resistance is your calling. Living Resistance helps us to hear that call and, more importantly, to answer it.

Curtice’s book is a response to the gut punch of COVID and the rise of right-wing extremism. It is also Curtice’s map of her inner life and transformation. She is one of many Native Americans who are discovering their roots, naming historical traumas, and reclaiming Indigenous teachings and identity. Curtice is a member of the Potawatomi tribe and of the Bear Clan, the “keepers of the medicine” in Potawatomi culture. She sees words as her medicine, and in laying out her journey of resistance, she offers her words and her life as a way to heal from the poisons of White supremacy, environmental decay, and personal trauma.