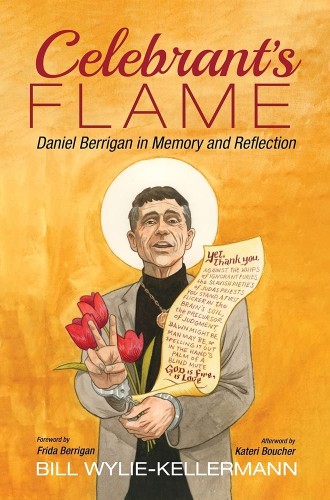

An ode to Daniel Berrigan

Bill Wylie-Kellerman’s patchwork of poetry, prophecy, and prose reads like a modern Gospel.

“If you have met Daniel Berrigan you have met Christ, because he dwelt within him.” So says one of the many voices whose harmony make Bill Wylie-Kellermann’s chorus of reminiscence for Berrigan sing. This patchwork quilt of poetry, prophecy, and prose doesn’t so much argue for Berrigan’s canonization as assume it—and thereby challenge the conventions of sanctity, as Berrigan himself couldn’t see a convention without perceiving its militaristic bias, its racist subtext, or its hypermaterialist presuppositions.

Reading this commonplace book of the extraordinary, an eyewitness account of the shaking of the imagination, puts me in mind of what the evangelists must have been working with when they compiled the Gospels. Berrigan’s explosive 1973 address to the Association of Arab-American University Graduates is his Sermon on the Mount. The direct actions he was involved in are his cleansing of the temple. Like the Gospels, his body of work includes the odd scrap of reworked prophecy—Berrigan wrote commentaries on every one of the Old Testament prophets. Then there’s the iconic 1968 action at Catonsville, Maryland, in which Berrigan, his brother Philip, and others burned draft files in a performance of sacred liturgy—call that his Q source. Put it all together and there you have a Gospel.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Yet Wylie-Kellermann resists the harmonization of an even narrative, preferring 12 chapters, each of which adopts a different perspective on this multifaceted man. The risk is repetition; the prize is a restless and relentless account to match the man himself.

Wylie-Kellermann devotedly assembles the cast of characters—the major prophets, like Dorothy Day and Dietrich Bonhoeffer; the fellow travelers, like Philip, Thomas Merton, Ernesto Cardenal, Thich Nhat Hanh, and the omnipresent William Stringfellow; and the countless disciples, with the author himself, who constantly recalls the spell Berrigan cast over him at Union Seminary in the 1970s, playing the role of Peter. Wylie-Kellermann writes:

Never had I met anyone . . . who thought in [the Bible’s] own idiom. Who read it from the inside out. Who expected to find therein the powers of this world demythologized and exposed, and who took recourse to the Scriptures in hopes of imagining the real world. Who thereby resisted the former and bet his life on the latter.

In a typical anecdote, Berrigan is hiding at Stringfellow’s Rhode Island home, slicing apples, when the FBI arrives to arrest him. After he’s gone, Stringfellow puts the apples in his freezer. Two years later, Stringfellow prepares a welcome home banquet for Berrigan, concluding with a pie made from those selfsame apples.

Yet despite its hagiographic tone, this constellation of reflections constantly portrays a Berrigan beyond the caricature: a phenomenally talented man of many languages, a man who while imprisoned learned T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets to distract from the enervating Catholic sermons he was hearing and composed subversive tracts to pass between incarcerated co-conspirators, a man who thought deeply about whether hammering a nuclear warhead was itself a form of violence, a prolific author who was Bible all the way down, a gentle friend who frequently put relationships before activism.

In the book’s most absorbing reflection, Wylie-Kellermann wrestles honestly with a life that was made for martyrdom yet lasted 94 years. (Again the reader wonders if Jesus, wisely advised to avoid Jerusalem that tricky year when Pilate and Herod were both in town, would have sipped bourbon with devotees long into his dotage.) The Catonsville action was perfectly crafted to be a Calvary moment, but it wasn’t. Yet Wylie-Kellermann returns to it over and over again as if it had been.

In what I found to be the book’s greatest revelation, Wylie-Kellermann discusses Berrigan’s close involvement in Roland Joffé’s 1986 film The Mission. The Mission is about Jesuits, the order in which Berrigan remained to the end of his life. It is full of iconic semi-liturgical moments, such as the fabulous crystallization of the native peoples’ conversion in the breaking and then offering of Father Gabriel’s oboe. The Mission is also about geopolitical events, in this case the carving up of South America between Portugal and Spain, and the complicity of the church amid the sacrifice of the common people. The film reaches its climax as Father Gabriel holds high the Host and dies under fire from the merciless Portuguese. Wylie-Kellermann tells us it was Berrigan himself who, besides appearing in many scenes in the drama, changed the final scene into active martyrdom. It’s hard not to suppose that such was the climax he envisaged for himself.

Eschewing the conventional portrayal of Berrigan as prophet, Wylie-Kellermann prefers to call him an apostle or evangelist of nonviolence. What emerges are the deeply Christian motivations of this deceptively simple man. The endless round of arrests and jailings, the community houses, and the discipline of nonviolence all constituted an ethic of resurrection.

But most striking is his sacramental ethic. Just as Jesus reinhabited the Passover at the Last Supper, so the Berrigans, in a profoundly priestly way, were involved in what Stringfellow called “the renewal of the sacramental witness in the liturgical life of Christians.” They thereby became aware of the social and political implications of the mass, always seeking that through their actions others might find life—not least by finding it more difficult to kill one another. Stringfellow described their direct actions as politically informed exorcism. Perhaps a culture in which exorcism wasn’t relegated to horror movies might have found their liturgical direct action easier to understand.

What Wylie-Kellermann is really doing goes beyond holding up Berrigan as the central figure in a contemporary Acts of the Apostles. His real agenda is to re-narrate the nature of discipleship, away from pious quiet times and earnest faith sharing at the coffee machine and toward intense, involved, and informed action in the face of racism, militarism, and rampant materialism. The book is saturated with anniversaries of events in a new liturgical calendar (Bonhoeffer’s hanging, Martin Luther King’s assassination, the Catonsville action), episodes that ring with a “Were you there?” incarnational quality, and confrontational conversations.

One young man, introducing himself to Berrigan, announced, “I’m dying of cancer.” Berrigan, without flinching, replied, “Gee, that must be exciting.” Whereupon the young man spent his remaining years aiding Vietnamese refugees. This is an uncompromising gospel for those who’ve lost interest in the anodyne one. It’s no good giving half of your life to peace: soldiers go to war knowing it might cost their lives, and peacemakers need to match that commitment. (And don’t forget, Daniel’s the mild one; Philip’s the one who confesses to giving in to hate at times.)

This is a very different church—more abrasive, but doubtless more faithful—from the one America is currently slowly rejecting. Berrigan himself put it thus: “We’re not trying to play God. We’re trying to play human.” Irrepressibly, irreverently, and irresistibly so.