A multitude of ways to love the earth

Mallory McDuff’s anthology centers non-White voices and women’s narratives in the climate justice conversation.

Minnesota attorney and activist Tara Houska—who also uses her Ojibwe name, Zhaabowekwe—knows firsthand how authorities respond when protesters challenge multinational energy companies on Indigenous lands. In December 2020, she and 21 others were arrested for impeding demolition crews set on installing an oil pipeline that would threaten the health of her community’s land and water. She tweeted that on several occasions police officers have responded to her and other Indigenous protesters with rubber bullets, tear gas, strip searches, mace, and detention in dog kennels.

Zhaabowekwe believes that the climate movement needs more than a quick fix. “I do not believe we will solar panel or vote our way out of this crisis without also radically reframing our connection with our Mother,” she writes in the 2020 anthology All We Can Save. She believes that Indigenous values provide necessary ideological anchor points and encourage a mutual relationship between humanity and the planet, unsettling the relationship of exploitation that advocates for a “green economy” sometimes fail to challenge.

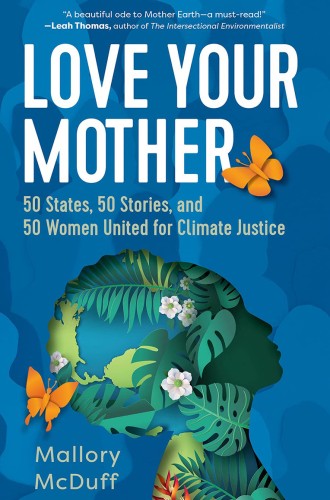

With stories like this, Mallory McDuff models how to situate regional geography, personal narratives by women, and local activism in the climate justice conversation. Love Your Mother tells the stories of 50 climate activists across the United States, curated to inspire and equip readers for climate change advocacy. The environmental educator profiles “change makers” from across a spectrum of experiences and backgrounds. The women range in age from 14 to 70, and McDuff centers non-White voices. Raw emotional honesty and authenticity seep through the pages; they are a balm for the ordinary days and a source of courage for the long haul of justice work. Together, the stories offer a timely message: you are not alone in this fight.