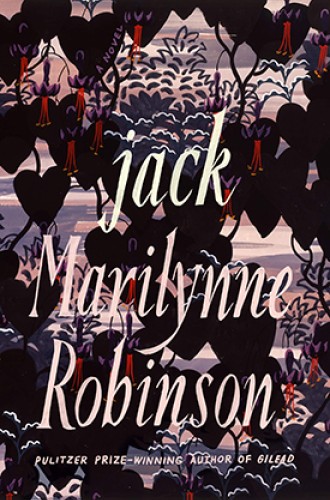

Marilynne Robinson’s new Gilead novel makes Jack Boughton make sense

Everything in Jack is a marvel.

In Marilynne Robinson’s fiction, characters register the presence of other people as a constant surprise. They say, over and over again, to themselves or to each other, things like, “I came into the nursery one morning and there you were,” or “There she was anyway,” or “Here he was in her kitchen,” or “Here she was in middle age.” They repeat variations on these phrases throughout the four novels (thus far) of the Gilead series, like people who tap a nearby wall just to reassure themselves that it and they continue to exist. A person’s bodily thereness—the indentation they leave on a pillow, their smell—is the supreme miracle, something so refulgent as to reduce the joys and pains that people produce almost, but not quite, to afterthoughts.

When Robinson published Gilead in 2004, the literary press reacted in much the same way to the sudden appearance of that book. Why, here she is. Where had this lovely, unfashionable novel—the story of a dying Iowa pastor, his colleague, and that colleague’s prodigal son—come from? And where had Robinson been in the 24 years since her classic first novel, Housekeeping? (She had been reading the entire Western canon and writing a series of scorchingly brilliant essays about the experience. But essay collections don’t get press.)

As masterly as Gilead is, every novel Robinson has written since not only has improved on it but, by adding depth and complexity to its story, has in a very real sense improved it. Home (2008), which makes apparent the passive racism of the elderly Reverend Boughton, depicts scenes of confrontation between father and son so searing that I don’t know if I can ever read it again. Lila (2014) gives a backstory to the wife of John Ames, Boughton’s friend and the narrator of Gilead, and it hangs a question mark over the future of their relationship. Together the three novels are, to my mind, the American literary accomplishment of our young century. Yet it’s hard to keep returning to Gilead, Iowa, when we know that with each trip we will witness these people whom we love suffering more.