Live not by a false sense of persecution

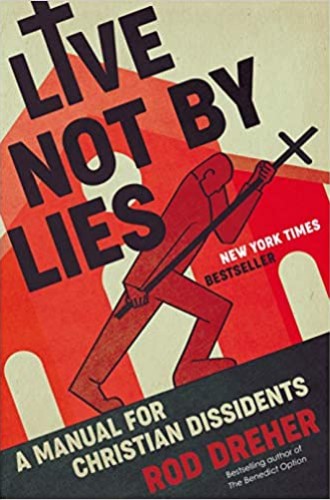

Rod Dreher’s Live Not By Lies is a damning testament to a religion without vision.

The one thing that kept me going through Rod Dreher’s latest book-length freshman term paper was the faint memory of a blog post. Dreher has been a house blogger for the American Conservative magazine for many years, and he’s used that platform to write constantly, instantly, and often intemperately about everything that grabs his attention. A few notions have escaped from the febrile pages of this blog to shape the wider American conversation on religion and public life, most notably Dreher’s proposal for a “Benedict option” of public withdrawal and internal renewal for conservative Christians, which he turned into an influential 2017 book. (See the Century’s review here.)

In February 2015, near the peak of American panic over the so-called Islamic State, Dreher wrote a post that I never forgot, called “When ISIS Ran the American South.” In it he compares ISIS’s spectacle murder by fire of a captured Jordanian pilot to similar spectacles of lynching in postbellum America. Noting that the Equal Justice Initiative, which extensively documented the lynchings, found ten instances in his home county of West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, Dreher says that he wrote to the EJI to ask for the full report. “I want to know who was killed, and under what circumstances,” he concludes. “These were our fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers, doing it to the fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers of our black neighbors. Attention must be paid.”

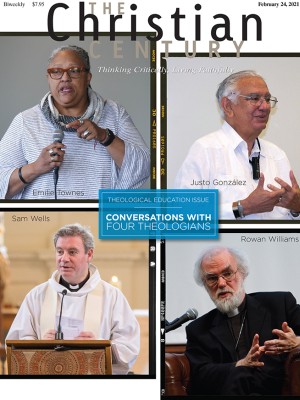

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Live Not by Lies is a bad book. But as a longtime reader of Dreher, I encountered it as a cliff-hanger. Would there be any echo of the 2015 blog post’s poignant and searching historical earnestness amid this slovenly new spin on American culture war politics? At the risk of spoiling the plot, the answer to that question is no. And therein, I suspect, lies a tale that concerns all of us.

The book’s premise is that America, and Western societies generally, either currently are or soon will be in the grip of what Dreher calls “soft totalitarianism.” The ideology of this new totalitarian order is what he calls “social justice,” which combines the racial and gender politics of wokeness or identity politics with a libidinous individualism that seeks to maximize personal autonomy and hedonic consumption.

The commissars of this new totalitarian order are college professors, professionals, and Twitter users who enforce the social justice orthodoxy by stigmatizing people who don’t confess it. Their influence has turned big business into “woke capital,” which can use the surveillance capacities of modern consumer technology to punish traditional Christians for not endorsing same-sex marriage and transgender rights—Christians, naturally, being the premier target of the ideology of social justice.

To endure this totalitarian onslaught, Dreher turns to the example of the Christians who were persecuted under Soviet-era regimes, portraying the Bolsheviks as the social justice warriors of their day and SJWs as the Bolsheviks of ours. (Dreher scatters historical analogies as widely as the sower in Jesus’ parable.)

This argument proceeds with the knowing hysteria of a John Birch Society tract from 1960. “Organize Now, While You Can,” implores one section header. “Can It Happen Here?” another heading asks. “Of course it can,” the text immediately answers. It goes on later: “it is coming, and it is coming fast.” But in fairness to the paranoiacs of the Birch Society, they sowed fear and suspicion toward teachers, librarians, and progressive clergy because they believed, however wrongly, that those Americans were part of a real thing: international communism. The social justice bogey hiding under Dreher’s bed is, at best, a composite.

Dreher never directly cites the people he claims are driving our world toward totalitarianism. He doesn’t acknowledge the differences between the managerial antiracism of Robin DiAngelo and the Afro-pessimism of someone like Frank Wilderson III, let alone the fractious debates within the broad left over whether and how to integrate ethnic, gender, or sexual identity politics with egalitarian economic goals. His definition of social justice comes from an atheist math professor, with rambunctious college students and tech industry titans massed into a single engine that rolls over everyone in its progressive path.

This depiction of modern politics will be familiar to the point of redundancy for anyone who has followed the “cancel culture” debates. Dreher invokes his side’s routine martyrology, lighting solemn candles for a tech CEO who lost his job for opposing same-sex marriage (and was forced to become the CEO of a much smaller company), an Anglo novelist who lost endorsements for her novel about Latin American migrants, White supremacists de-platformed by PayPal, and a pizzeria in Indiana that briefly closed due to a firestorm of online criticism for its refusal to host same-sex wedding receptions.

There’s nothing original or insightful in the first half of the book, merely a phalanx of clichés and charging back and forth across the same field. George W. Bush’s “war to liberate Iraq for liberal democracy failed,” Dreher writes,

but drinking deeply of [his] intoxicating rhetoric makes it easy for Americans to forget these things. It’s not necessarily because we are foolish; the Myth of Progress is written into our cultural DNA. Perhaps no country on earth has been more future-oriented than the United States of America. We are suckers for the Myth of Progress—but to be fair, we have reason to be.

The Myth of Progress is another composite. Perhaps it’s an intoxicant we consume, or else it’s woven into our metaphorical DNA. It may be a con we’ve fallen for, or it may be rational. A writer should settle this for himself, if not before writing, then at least before concluding. Consulting the actual views of people on the left—who are not notably optimistic and do not tend to think they’re winning, let alone on an inevitable march to triumph—would have helped.

The book’s latter half is taken up with the “manual” part of the title. It includes the moving and charismatic stories of Christians in the Soviet bloc whose forms of resistance and ordinary courage Dreher translates into obvious but mostly inoffensive advice for living under totalitarianism. (One tip: read Tolkien to your children.)

Those stories, shorn of context though they are, make up the book’s most worthwhile moments. And they help answer the only question the book raises that is worth thinking about: Why did Dreher choose to write a book about Central and Eastern European Christians living under Soviet domination?

After all, there are more revealing and relevant examples of life under persecution from our own national history and our own era. Black Christians and their often rather few White allies could furnish plenty of examples of the terror, official deception, and ideological doublethink under which they had to preserve their faith and their communities from slavery through Jim Crow and beyond. This is living memory with ongoing, visible effects. It seems plausible that if we experience a real authoritarian degeneration in America, it will look something like what we did to ourselves in the recent past.

Or Dreher could have looked to Christians in areas of the world presently experiencing democratic decline and liberal retrenchment. State domination of the media and civil society is growing in many places, including such bastions of cultural Christianity as Russia, Hungary, and Poland. Procedural protections and civil rights are under threat right now around the world.

One reason to overlook these close examples is that the threat of communism is the only thing that can gloss over the identity crisis within the American right. Conservative intellectuals don’t have a consensus on what their movement is for or what problems it is supposed to be solving. Marxism needs to do all the work of holding a fractured and uninspired tendency together.

This, presumably, is why someone like Senator Josh Hawley needs to work out a way to say that Silicon Valley tech firms are Marxist. Or why former senator Kelly Loeffler claimed in campaign ads that the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta would be America’s first Marxist senator. These are the decades-old hits of a band on the county fair circuit.

But, at least in the case of a wide-ranging gadfly like Dreher, telling this particular story reflects not just Cold War nostalgia but more recent developments on the intellectual right. Religious and ideological identity is only one axis for the conservative understanding of modern politics. The other axis is ethnic and cultural.

Talking about Christians in Soviet Eastern Europe offers Dreher and his audience both a villain that is ideologically other (namely, communist) and a protagonist who is ethno-culturally self (European and Christian). The story of Christianity under racial apartheid in America, democratic retraction in contemporary Europe, or criminal and failed states in Latin America would require Dreher and his readers to face the possibility of identifying with the persecutor or being estranged from the persecuted.

There was a time, even as recently as that anguished reaction to the EJI report on lynching, when Dreher demonstrated the ability to see his own cultural identity as entwined with and complicit in grave evils. Now he invokes “redlining” in reference not to the actual American practice that created housing segregation and massive wealth inequality but to a future possibility that right-wing influencers may not be able to bank at JPMorgan. He describes the hardy Christian resistance cells under communism as “sanctuary cities” at a time when literal sanctuary cities—meant to keep immigrant families intact and limit the power of the federal government to invade and destroy lives—are being dismantled. He devotes a chapter to “Standing in Solidarity” while writing on his blog that George Floyd was a victim of his own refusal to obey police and Breonna Taylor would have been just fine if she’d internalized good values like Dreher’s father had.

There was a time when Christian immigrants from Africa or Latin America were viewed as potential allies for American Christian conservatives. Now they’re a threat to Western culture because, as Dreher repeated in a blog post defending Trump’s comments about “shithole countries,” Africans defecate on the street. For all his avowed devotion to Christianity, it’s clear that Dreher would rather be the lone Christian in a neighborhood of atheists who put up Christmas trees for cultural reasons than the only White person in a neighborhood of Senegalese Christians.

Dreher is not the only writer who has murdered his own conscience in broad daylight over the last several years. This is more than a personal tragedy; it’s a tragedy for a politically and culturally engaged Christianity that will, one way or another, have to decide whether to be loyal to a universal faith or a narrow and contingent culture.

Dreher could have pointed out in this book that the surveillance powers of modern capitalism can be, and in fact are, used vigorously against immigrants and racial justice protesters as well as White conservatives. He could have acknowledged the online mobs that targeted Comet pizzeria, to the point of an armed attack, under the influence of right-wing conspiracy theories. He could have mentioned, even in passing, the White supremacist attacks in Pittsburgh and El Paso, the jobs lost by labor organizers and other leftist dissidents as well as conservative CEOs, or the political implications of our own system of mass imprisonment. The banner of threatened freedom can stretch farther, and the arms of solidarity open wider, than the little portion of America Dreher cares about.

Instead we are left with a damning testament to a politics that no longer seeks to persuade and a religion that no longer inspires any vision of justice. Live Not by Lies is a message for people to turn on their potential allies with fear and disgust when they might link arms, across cultural and generational divides, to defend each other from their bosses, creditors, and the demagogic politicians who fail at the basic tasks of governing.

As Trump supporters stormed the Capitol on January 6, carrying Confederate and thin blue line flags, I checked in on Dreher’s Twitter feed. He was horrified and angry at the people who had stoked that particular mania. A few hours later, he had righted the ship. While the mobs and the demagogues and charlatans who spurred them on were criminal, regrettably hoodwinking some good conservatives in the process, their actions could only be understood “in context of what the Left has been doing” for much longer. The “factories” of anti-White “race hatred” are provoking this regrettable excess. Does anyone think “that white people are going to sit back and do nothing” in the face of so much provocation?

One imagines similar sorrowful words having come from the decent folks in West Feliciana Parish ten times and more after the fatal violence they inflicted. Attention, indeed, must be paid. If it isn’t, the bill only compounds.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Who’s a persecuted Christian?”