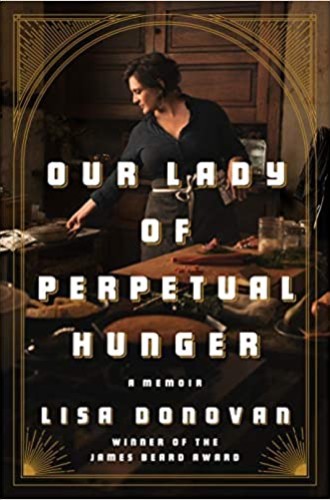

Lisa Donovan tells the stories behind the recipes

Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger exposes the misogyny within the restaurant industry.

Cooking got me through a year of staying at home during the pandemic. As I recently baked a shoofly pie, adapting my grandmother Anna’s recipe for the Pennsylvania German molasses treat, I felt a kinship with Lisa Donovan, a chef who has won acclaim especially for her desserts.

After proving herself in the expected French cuisine, Donovan found that what classic recipes taught her “in precision and technique, they lacked in story and real-life meaning.” In search of this missing dimension, she adds, “my nose was firmly planted in every church cookbook, every ladies’-guild or school-fund-raising cookbook, every old stapled or spiral-bound book of cakes and pies and divinity candies that I could find.”

As Donovan elevated those pies and cakes to the level of fine dining, she also pursued the stories and recipes of her own women ancestors. She recounts talking into the wee hours of the morning with her 91-year-old great-great-aunt Ruby, absorbing family tales and learning how to make dried-apple hand pies. The 150-year-old recipe includes cream and black pepper and as much cinnamon as was available, which together mimic the nutmeg and cloves that were hard for Appalachian farmers to find. “I understand now why it has always been a transcendent experience for me” to shape flour into dough, Donovan writes,