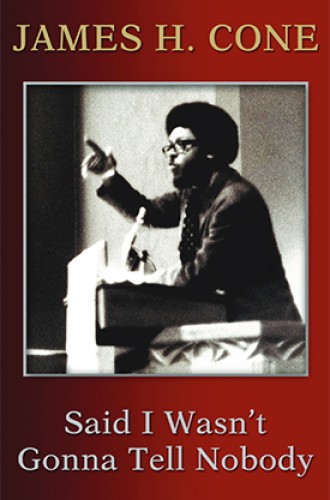

James Cone and the liberating spirit of blackness

In his final memoir, Cone’s testimony resounds.

If there was ever a time we needed James Cone with his powerful prophetic voice to call down thunder, that time is now. Like a blues musician, Cone inhabits the souls of those whose voices cry out to be heard, and like the soul preacher and spirituals singer he is, he testifies to the liberating spirit of love that grows out of embracing blackness. In Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody, Cone preaches more fiercely than in any other of his previous books, declaring: “The blood of black people is crying out to God and to white people from the ground in the United States of America.”

While Cone’s physical voice is now silent—he died earlier this year—his written voice cries out in this memoir, compelling us to listen as he testifies. His testimony includes some already well-known details about his life (which he described in his 1982 memoir My Soul Looks Back) and analysis of how they shaped him. But this new memoir also contains much more: his experiences writing his books, the challenges he faced from critics, the passion that urged his words onto paper, and the new theological language in which he was writing—“the language of the black sermon and song, and in the spirit of the great preachers and singers I had heard all over Arkansas and in Chicago and Detroit.”

From his early engagement with Karl Barth’s theology to the four books on black liberation theology he published between 1969 and 1975, Cone demonstrated that his authority for doing theology comes from black experience and not from claims to divine revelation. Looking back on those years, he explains, “I did not want to write anything that black people would not understand and read and hear as their own experience. If I couldn’t preach it, I wouldn’t write it.”

Engaging with the Black Power movement “saved my life as a theologian,” he writes, because the stakes were so much higher than in European theological debates: “It didn’t matter whether Barth or Harnack was right in their debate about the meaning of revelation. I wasn’t ready to risk my life for that. Now with Black Power, everything was at stake—the affirmation of black humanity in a white supremacist world. I was ready to die for black dignity.”

Cone structures this memoir with the words of the gospel song “I Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody.” Using individual lines from the hymn as chapter titles—such as “you ought to been there” for a chapter on his writing of A Black Theology of Liberation—he moves from exclaiming that he couldn’t keep his blackness to himself in the first chapter to “singin’ and shoutin’” as he tells about what he learned from James Baldwin in the final chapter. The writing dances across the page, echoing the music of Cone’s soul. Every page resounds with striking chords and notes that fill readers with urgency.

He captures his own experience of writing playfully and soulfully:

I was writing out of experience, speaking for the dignity of black people in a white supremacist world. I was on a mission to transform self-loathing Negro Christians into black-loving revolutionary disciples of Jesus Christ. I was singing a new theological song, a blues song, messing with theology the way B. B. King messed with music. I used Barth’s theology the way B. B. used his guitar and Ray Charles used the piano.

Cone explains why black theology is uniquely improvisational: “Black liberation theology came out of black culture and religion, and it celebrated a new freedom to talk about God and Jesus in a jazz mode, a blues style, and with the sound of the spirituals. That was where its mojo came from—its magic.” But the spiritedness of Cone’s language doesn’t diminish the seriousness of his message. “I wanted to wake up black people and let them know that the day of the white Christ was over. A new Black Messiah was in town.”

Cone proclaims the centrality of the black Christ to his theology. From his earliest work, he says, “I was deeply Christological in my orientation.” But his focus on Jesus didn’t derive from the sources his professors and theological mentors had relied on. He explains,

Black theology’s spirit did not come from Europe but from Africa, from American slavery and its auction blocks, from the spirituals and the blues. The Christocentric power of black theology was defined by the Black Christ who enabled black people to survive slavery, to overcome Jim Crow segregation, and to defeat the lynching tree. The Black Christ was a black slave and “a black body swinging in the southern breeze.”

Although Cone roots his theology in black experience, he also proclaims that Christ—“a dark-skinned Hebrew who died fighting for the freedom for his people”—dissolves any purported dichotomy between black experience and revelation. “God in Christ did not make an absolute distinction between divine revelation and the black experience but rather took that experience as God’s own reality.”

Reflecting on how these ideas shaped The Cross and the Lynching Tree, Cone explains what’s at stake:

Lynched black bodies are symbols of Christ’s body. If we want to understand what the crucifixion means for Americans today, we must view it through the lens of mutilated black bodies whose lives are destroyed in the criminal justice system. Jesus continues to be lynched before our eyes. He is crucified wherever people are tormented. That is why I say Christ is black.

Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody testifies to a message that we sorely need. If we fail to listen to Cone and allow his words to live in our hearts and our actions, we fall short of our Christian vocation to love our neighbors and to liberate the captives, the marginalized, and the oppressed.