Intersex at Bible college

In telling a student’s story, Cynthia Vacca Davis captures the complicated nature of coming of age as an intersex person.

Lines are all around us. Having been raised and educated in fundamentalist evangelical contexts, I saw lines clearly drawn around everything from sin and salvation to sex and gender. It was the latter that triggered my questioning of the traditional demarcations I was taught to embrace and defend. My journey in discovering my intersex variations and navigating gender dysphoria challenged my addiction to answers and pushed me toward what Cynthia Vacca Davis eloquently calls an “acceptance of the space around the lines as a necessary part of the image itself.” Intersexion cultivates this sort of space as it tells the stories of two people: Davis, an adjunct professor at a conservative Christian school, and Danny, who entrusts Davis with his story of being intersex in a conservative evangelical community.

I approached this book cautiously. Davis is both cisgender (someone whose identity and biology match the gender they were assigned at birth) and endosex (someone who has biological traits primarily consistent with accepted definitions of male or female). As she notes, intersex traits (the blending of organs and systems typically assigned to either male or female anatomy) are much more common than most people are aware. Often these traits go unnoticed, adding to the obscurity of their frequency. While the presence of such traits often complicates gender identity, not all intersex people are transgender (experiencing a shift away from the gender assigned at birth and adopting a gender expression more suited to their psychological makeup). For those who, like Danny and me, are transgender, trusting a cisgender person with our story can be tenuous.

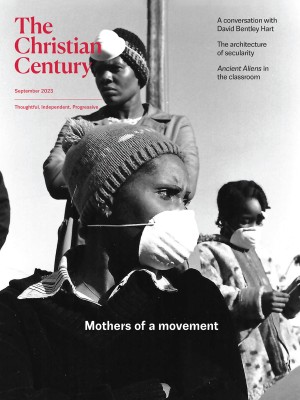

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It only took a few paragraphs for me to let my guard down. It quickly became clear that Davis is a gifted storyteller. The readability and relatability of the narrative allow the process of storytelling to fade effortlessly into the background while the intricacies of the subject matter emerge.

The first half of the volume is devoted to telling the story from Danny’s point of view. It’s a bold choice to present someone else’s story in first-person narrative, but here it pays off. If, as a reader, you are sensitive to being told rather than shown a storyline, I would invite you to muscle through the first half of the book; the author’s ability to paint a word picture comes much more alive when, in the second half, she switches to her own first-person narrative. That being said, Davis does a wonderful job capturing the complicated nature of adolescence for intersex youth, especially for those of us who grew up with the lines Danny and I did.

What becomes even clearer as the story unfolds is Davis’s desire to learn and grow as an ally to intersex and transgender people. I found myself envious of the allyship that Danny finds in Davis and her husband, as well as in other friends and relationships that emerge along the way. The physical, emotional, and spiritual hurt that LGBTQ people experience, largely at the hands of insensitive friends, family, spiritual leaders, and other authority figures, cannot be overstated—and Davis goes to great lengths to point out this struggle, from the terror of disappointing family to the imposter syndrome in dating.

The confusion through which intersex people are forced to engage the world is summed up well in this statement from Danny about having to dress for gym class in a junior high girls’ locker room: “I knew from those changing sessions that I wasn’t physically female. But as much as it hurt to admit, I wasn’t male either. What was I, then?” It’s a question no preadolescent, or human of any age, should ever have to ask alone.

It would be impossible for me to detach my own experience from this reading. There were times I felt as if Davis were writing my story: military family, check; school years on the Virginia Peninsula, check; childhood crush on Amy Grant, double-check; playing guitar for high school youth ministry, check; Bible school in Chicago, check. I related deeply to Danny’s story, and from that stance, I invite you to read Intersexion with a few specific goals in mind.

First, sharpen your empathy. The only way to fully understand gender dysphoria (the psychological term that describes the experience of mismatched gender) is to have personally experienced gender dysphoria. That reality is driven even deeper by the physical implications of intersex traits. Short of that experience, which I would not wish on anyone, the next best thing is to listen to our stories. Davis has done our community a great service by packaging Danny’s story in a very digestible manner.

Second, join Davis in her quest to become a better ally. Make notes of the words she uses to describe Danny’s experience and look them up to better understand them. Don’t take anything for granted when it comes to the details that make our life experience different from yours. Use the catalyst of Danny’s story—and any subsequent news stories, legislation, and critiques related to transgender people—to help others develop greater empathy.

I have sat in many boardrooms like the one Davis describes at a notably unnamed Bible college, addressing the concerns of conservative Christians who are oddly put at ease by the fact of my intersex personhood—as if my suffering somehow justifies my transgender experience. While transgender people do not need justification for their personhood, Davis uses nearly the same words I have uttered when trying to help conservatives develop greater empathy: “People you might think of as ‘just wanting a sex change’ could still have a biological basis for the disagreement they feel with their assigned gender.”

Finally, don’t assume you need to fix us. We are not broken because we sit outside the lines of traditional gender. We are challenging and challenged by a system that depends on those lines for its comfort. Davis puts it well: “Rigid lines—even fine ones—make for flat, simplistic images. Realistic renderings rely on blending—a gentle back and forth smudging of colors and borders that replicate the muddling interplay of shadows and light.”

“Muddling interplay” may be the best description of the most beautiful and painful parts of my life, parts that I see playing out in Danny’s story as well, and parts that I hope you will invest the time to explore.