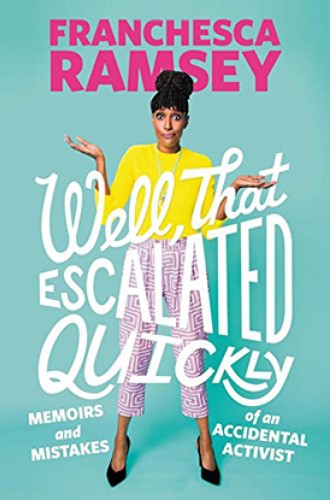

How I got schooled by Franchesca Ramsey’s hilarious memoir

Ramsey shows the high stakes (and common mistakes) of online activism.

I loved Franchesca Ramsey’s memoir from the very first sentence, where she confesses that if she could redo her breakout moment of viral YouTube fame, she’d have worn a better wig. Her hilarious 2012 YouTube video “Shit White Girls Say to Black Girls” hit an obvious nerve. Six years later, it has 12 million views.

I knew Ramsey best for her sharp and funny video commentaries on MTV’s Decoded. On a quest to learn more about my new home state, I’d watched the Decoded episode that explains why certain states are so white. (Oregon’s racist history is such a standout, we get an extended cameo in the episode.) Ramsey’s videos are both hilarious and packed with mind-blowing facts.

Ramsey uses her trademark humor to disarm her readers and then reequip them with better tools. In other words, she schools us. But whereas a page of Austin Channing Brown or Ta-Nehisi Coates can feel like a sucker punch to anyone breathing the white supremacist air many of us don’t even realize we are breathing, reading Ramsey’s satire feels more like rolling on the floor laughing with our wittiest bestie.