Going offline to preserve the precious resource of attention

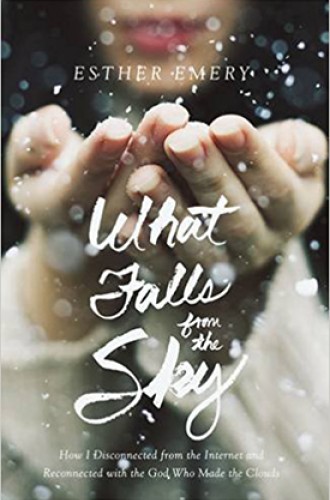

Yes, it's another year-of narrative. But Esther Emery offers a moving story about the possibility of change.

On a winter night in Southern California around the turn of the decade, Esther Emery was pulled over for reckless driving. Emery and her husband, Nick, were at the time temporarily estranged. Her career as a playwright and theater director was soon to unravel. She was pregnant with her second child. Late to meet a friend, Emery entered the freeway and pressed the car’s accelerator until the needle slid past 100 miles per hour, then 110. She recalls laughing when the police officer asked how much she’d had to drink. Her problem wasn’t alcohol. Her problem was runaway ambition, or fear, or fury. Her problem was a taste for perpetual acceleration, “the only thing I had really been trained to do.” Her problem was she was not wholly sure what her problem was.

That story scene opens Emery’s wise, lyrical memoir of a year spent without Internet, a semi-improvised attempt to remedy the fatigue and “creeping numbness” of a life lived at untenable speeds. During this year, Emery reawakens to parts of herself lost amid digital distractions. She finds her soul being reconfigured by silence and an unforeseen hunger for God.

Year-of memoirs—or annualism, a term coined by the BBC in 2009—have a history in American letters dating back to Thoreau, who collapsed his two years, two months, and two days at Walden Pond into a single calendar year for his venerated opt-out narrative, Walden (1854). Stories of yearlong experiments in unconventional living have been so plentiful of late that readers could play a mean game of Jenga with titles belonging to this subgenre. (Google the Goodreads list of “A Year in the Life” memoirs and imagine publishers trying to place one more Jenga block atop the rest. It’s mildly amazing that the tower has not toppled.) Given this craze, I admit approaching Emery’s tale of her year without Internet reluctantly, steeled against the year-of game.