Georgetown was built on the backs of enslaved people

Reparations for their descendants are a necessary, imperfect beginning.

I can’t think about this book without remembering the parable about blind men and the elephant. You know the one: after touching only one part of an elephant, each man insists that the elephant is like another object with which he is familiar, like a broom or a tree. It’s usually told to illustrate that clinging to a singular, subjective worldview limits access to truth. But I favor a more ambiguous reading: while a limited perspective is, well, limited, digging deep into what’s accessible to you can also speak to a truth too large to grasp all at once.

This idea—minus the elephant, of course—is at the heart of Facing Georgetown’s History. Georgetown University, founded in 1789 by Jesuit priests in Virginia, is positioned in this volume as “a microcosm of the whole history of American slavery.” As Lauret Savoy notes in her foreword and several authors echo throughout the book, careful study of Georgetown and other major American universities offers a window into the ways in which America and its institutions were built on the backs of enslaved people. “Entanglement with slavery . . . was never accidental or temporary,” she writes. “It was deliberate, invested and committed.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

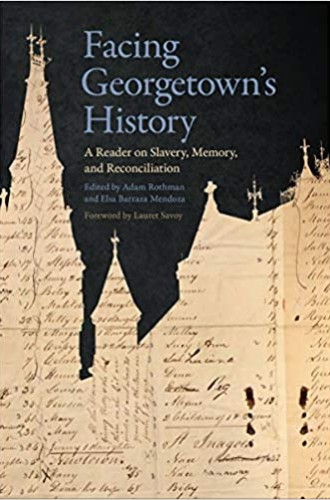

Edited by Adam Rothman and Elsa Barraza Mendoza, this collection of academic articles, journalism, primary sources, and speeches largely succeeds in providing a comprehensive and nuanced approach for grappling with the history of slavery and the question of reparations—a feat made possible only through the book’s limited scope. There are flashes of the wider national conversation—Savoy’s introduction, for instance, and a reprint of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “The Case for Reparations,” which takes not Georgetown but Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood as its lens. But these traces appear only often enough to ensure that readers never forget that Georgetown’s history is just a sliver of a larger problem.

We learn that although they themselves were suppressed in the United States, Jesuits, like most Catholics, did not morally object to slavery and were often cruel enslavers more concerned with public appearances than with the well-being of the people they owned. We’re told that early Georgetown students often bartered the labor of enslaved people for tuition and that Catholic women in the Georgetown area leased enslaved people to the university. And, most crucially, we follow the story of the 272 enslaved people sold by Georgetown in 1838 to repay the university’s debts and then shipped against their will to Louisiana. Their story was brought to light and branded as GU272 by student activists, and their descendants were found and swept into the debate around reparations.

That description undersells the GU272’s descendants’ story, which is told in the later sections of the book. Through essays, speeches, and newspaper interviews, the descendants of the GU272 emerge as a group of people with diverse approaches to their family history and various feelings about Georgetown and its responsibility to repay them. This highlights the enormity of the issue of reconciliation and reparation.

As the Georgetown of the 21st century grapples with ways of identifying true descendants (via surname or direct-to-consumer genetic testing), offering formal apologies during a public ceremony (attended by both gracious and ambivalent descendants), extending legacy status to descendants, and considering building schools in Maringouin, Louisiana, where many families of the GU272 remain (in a community that is by turns approving and reproachful), the university is depicted as well-meaning but bumbling in a way that seems to say “at least they tried.” The clear argument is that the rest of America and its institutions should also try, and try harder.

Though this is not the most flattering light in which Georgetown could be cast, Georgetown’s institutional reputation is not harmed. It is, in fact, bolstered. This is the most compelling argument made in the text—that it is worth it to make public blunders, to do something even if it could never be enough.

The most powerful element of Facing Georgetown’s History is its careful way of making this dark history both personal and global. Through primary sources, readers learn the names and ages of each of the GU272. Savoy is correct when she writes that although we don’t hear their voices directly, we get a real sense from these documents of the world the GU272 inhabited, down to the provisions made for them in university budgets and GU272 member Frank Campbell’s crooked posture in a photograph reprinted in the volume.

Especially moving is the story of Mélisande Short-Colomb, a 63-year-old GU272 descendant who enrolled as a freshman at Georgetown after the university granted legacy status to that group. Short-Colomb is profiled in a Washington Post story, and she appears throughout the section titled “Reconciliation and Reparation” at the end of the book, describing herself as a resource to her younger classmates. She serves as evidence of the unexpected benefits of initiatives like those at Georgetown.

Facing Georgetown’s History is not perfect. It’s unclear to me who the volume is meant for, presumably because it is intended to reach as wide an audience as possible, which leaves it somewhat disjointed. Some dense and highly specialized academic articles appear next to primary sources framed by reflection questions more appropriate to a high school history textbook. Reprints of articles from the Atlantic and the Washington Post appear next to editorials from Georgetown’s student newspaper, the Hoya, with only brief summaries from the editors for context. It makes for a somewhat jarring read if, like me, you read the book cover to cover rather than as selected pieces, as I imagine a researcher or student might.

Still, Rothman and Mendoza provide a highly nuanced, multifaceted look at the history of slavery and reparations at Georgetown University. This is a valuable and compelling entry into the wider discussion about reparations in America.