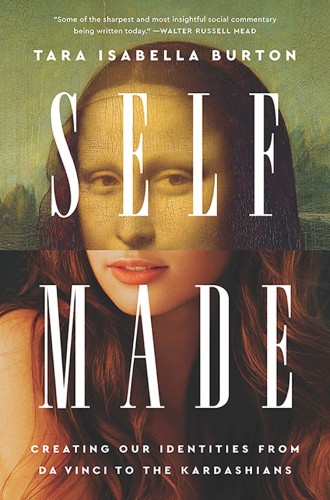

The genealogy of selfhood

From the Renaissance to Kim Kardashian, Tara Isabella Burton tells a story of limitless, ruthless self-creation.

It was the kind of pop culture ephemera that I would typically forget: a 2007 radio ad for a reality show about people I’d never heard of, doing things I didn’t know anything about. Maybe it was the uncommon family name or the alliteration of Keeping Up with the Kardashians that grappled into my memory. In the following years, I never saw the show (which ran until 2021), followed breakout star Kim’s Instagram, or purchased any of her many products. Despite not knowing where she came from or what she, for lack of a better word, did, I feel like I’ve always known what she looked like, who she married and divorced, and the fact that she was a famous person: who she is.

Kim Kardashian had osmotically seeped into my brain through checkout-counter magazine covers, gas-pump screens, and random news items. She is “famous for being famous,” a disdainful phrase that avoids her real accomplishment. She made herself into someone everyone would know. She optimized herself to master, at least for a time, what Tara Isabella Burton in Self-Made calls “a digital landscape where our attention is the building block of reality.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

How did this kind of fame—enigmatic, iconic, and somehow omnipresent—become possible? How has it become so necessary to form our very personalities in the image of our own and the world’s desires? And how have we come to understand success and failure when we, from the humblest gym goer to the most overexposed celebrity, are our own projects?

In a cultural history spanning five centuries and crisscrossing the Atlantic, Self-Made provides a genealogy of the modern idea and practice of selfhood. Against the constraints and inequalities of fate, circumstance, and community, Burton claims, we operate under an unstated but universal assumption that “who we are–deep down, at our most fundamental level—is who we most want to be.” And, just as importantly, what we can convince the world we are.

Burton’s story of limitless, ruthless self-creation begins in the Renaissance, with the precociously brand-aware painter Albrecht Dürer. Like so many of the figures who followed, the celebrated portraitist of kings, wealthy burghers, and (significantly) himself “didn’t just make art; he transformed himself into a work of art.” This is the first great age of the unpedigreed genius, as Dürer and his contemporaries broke medieval conventions of anonymous artistry, Castiglione taught literate Europe the mannerisms of the aristocracy, Pico della Mirandola revived ideas of the grandeur and perfectibility of human nature, and Machiavelli instructed would-be rulers on the moral latitude and image management needed to gain and keep power. In art and politics, it became possible for upstarts to imagine fashioning themselves into people who could climb the supposedly fixed social and natural order in which they lived without fundamentally altering its structure.

The Renaissance provides a template for the periods that followed, each opening a new vista on the shifting horizon of the self while elaborating the constraints discovered, or erected, as human beings move toward it. Where the Renaissance luminaries taught self-made people how to adopt elite customs, the Enlightenment thinkers “disenchanted” custom entirely and pushed up to, and beyond, the brink of questioning the religious and political orders altogether.

In Europe, new wealth from colonial expansion and industrial development led to the rise of self-invented tastemakers who used clothing, manners, and a blasé affect to enter and shake up the existing aristocratic hierarchy. Encompassing both the high style of Oscar Wilde and the amoral depredations of the Marquis de Sade, and issuing finally in the pompous artificiality of Italian fascism, the self-made man in what Burton calls the “aristocratic” style emphasized his victory not just over inherited custom and emerging democratic norms but over nature and society. (A funny running bit in the book is the number of figures who add a bogus “de” to their family names to feign an aristocratic pedigree.)

In America, with no proper aristocracy to disrupt, a “democratic” and “entrepreneurial” style of self-making develops, with the goal of improving and cultivating one’s own inner resources. Starting with Frederick Douglass, the American story passes through Gilded Age robber barons and inventors, the highly stylized personalities of Andy Warhol’s Factory, and the techno-utopians of Silicon Valley to the present age of social media celebrities and viral content producers, all harnessing the spiritual or mystical energy of the universe to bend reality to the optimized will.

Through all the centuries and fashions, the story of self-making is defined by the tension between ideas of “innate superiority and social fluidity, between aristocracy and democracy.” Some of us achieve ourselves, while others are consigned to a “psychic underclass,” too graceless or lazy to shape the world to our desires. But all of us have to keep trying—not just to be our best selves but to make a commodity of those selves. Whatever else you can say about Kim Kardashian, she has undeniably succeeded in the very terms established for her—and not just by modern media or late capitalism but by a long tradition of visual culture, business thought, and philosophical speculation.

Burton uses a wide lens to capture her history, going well beyond canonical literature to pulp fiction, clothing, manners, consumer fads, and outright frauds. And she is careful to situate the ideas she describes in their economic and technological contexts, rather than treating them as protagonists in disembodied combat. This distinguishes Self-Made from the genre of conservative polemics that treat the trajectory of post-Renaissance cultural history as a long theological or psychological decline from good ideas and stable roles to bad ideas and moral license, a prehistory of the contemporary cultural wars connecting Machiavelli to Marx to marriage equality.

Applying the claims of Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age, Burton does acknowledge that we live in an age of “expressive individualism” that would be radically unintelligible to the medieval mind, to which human beings are fully created as part of an integrated and essentially unalterable whole. But Self-Made is a story of neither decline nor liberation. It’s a story of evolution in which both progressive and reactionary politics and culture today are fully embedded.

The mechanisms of self-making have, indeed, opened avenues for social mobility that were unknown in each previous era. But, as Burton makes clear, they have until relatively recently been mostly unavailable to women, who, if anything, were objects of disdain or worse in the liberated imaginings of de Sade and his paler imitators. Nor were they easily accessed by racial and ethnic outsiders, and only on very limited terms by anyone who fell outside of a given society’s conventions of gender or sexual expression. The cult of self-making divides poor people into a few shining examples of social mobility and a torpid mob of failure, while simultaneously obscuring the difference between the genuine innovator and the humbug artist.

It is easy to conclude that these are not mere oversights or imperfections in the story of universal self-creation but rather integral to it. All that glitters is not gold, but it catches the same eyes. Old inequalities may fade, or they may change shape, even as new forms of hierarchy are invented.

Whatever has been gained in this sprawling journey toward universal self-creation has come at the cost, Burton suggests, of suppressing important aspects of our own humanity. True selfhood would require us to acknowledge the parts of ourselves we might efface for online clout, political influence, or financial success. It would require us to acknowledge rather than deny the roles of community, contingency, and vulnerability that shape us whether we want them to or not. If we don’t, we are “liable to mistake our ordinary human desires, and ordinary human efforts, for spiritually potent forces with the psychic or moral power to bring us fame, riches, or superiority to others.”

All of this comes in a brisk, erudite, and uncommonly pleasurable trip through the ages. So it is equivocal praise to say that I found myself wishing Self-Made would not end. Its story could have started earlier; I would love to read Burton on a self-conscious striver like Cicero or Bernard of Clairvaux. But this would require breaking the historical frame, coming from Taylor and others, that treats the “medieval worldview” as a real thing of coherence and unquestioned consensus rather than an ideological artifact obscuring the very real conflicts within the church, state, and economy. Whatever changed in the era of Dürer and Da Vinci, it wasn’t the ability of human beings to abstract their individual consciousness from their social order or to question its fundamental rationality.

More importantly, the story could have pushed later and deeper into our present era’s nexus of self-fashioning and cultural influence. Burton is a shrewd observer of online culture, particularly the recently ascendant strains of right-wing provocation and crackpot political theory. These intellectual circles are rife with the frustrated social striving, sartorial dandyism, and aestheticized religion so prominent in Self-Made (and, for that matter, in Burton’s two fine novels). Similarly, Self-Made could have served as a genealogy of the current entrepreneurship, and sometimes fraud, relating to illness and identity. Our age has given us both Rachel Dolezal, an academic who pretended for years to be Black, and Bronze Age Pervert, a writer and podcaster who plays at reviving paganism based on cultural and racial resentment. I wish Burton had taken us into the mirrored hallway of stunted professional ambition, craving for deference, and grandiosity that provokes such odd self-imagining.

Any good cultural history will, however, leave the reader with unanswered questions about what the story leaves out and where it might go next. Burton’s diagnosis of mandatory striving and self-creation adds useful depth to our public discourses about inequality, media influence, and mental health. The story of people who have successfully performed modern selfhood is, ultimately, the story of what happens to their audiences—the masses whose attention creates reality, yearning for intimacy with our world’s winners but scorning their real vulnerability, aspiring to embrace and supplant them in one movement. The possibility that we may fail not only at a career or a particular project but at the very task of being ourselves might destabilize whole societies as well as individual lives.

Economic and psychological vulnerability reinforce each other: If I am not what I want to be, nor what anyone else wants me to be, what am I? For a society of self-made people, limited social prospects are congruent with emotional woundedness. We become ever more vulnerable to delusions or to projecting our needs onto charlatans and authoritarians. Kim Kardashian was a puzzling Rorschach test; a Kim Kardashian with an aggrieved, emotionally stunted militia is a nightmare we are already starting to experience.

The culprit, for Burton and others following Taylor’s description of secular modernity, is the absence of meaning or significance in the postmedieval world. Where once we might have taken the purpose or coherence of our lives, however small, for granted, now we are all doomed to an untethered search to find or make them for ourselves.

But if this is true, we will need to start making stronger claims about what human life should be. To acknowledge our own contingency and need for others, as Burton insists we must, is the beginning of wisdom in a world of self-making. But it is only the beginning. A good life, and a coherent self, still awaits its portrait. The cultural historians have, so far, only interpreted the self. The point really is to change it.