Discipleship through covenant friendship

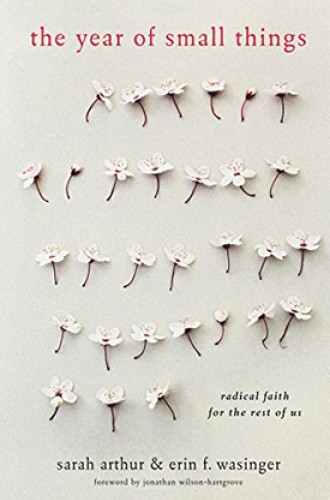

Sarah Arthur and Erin Wasinger write about their experiment in radical faith, one small step at a time.

Perversely, high hopes can lead to inaction. Grandiose dreams can bog us down. As P. J. O’Rourke once put it, everyone wants to save the world but no one wants to do the dishes.

The Year of Small Things is about doing the dishes. It’s about the hard work of serious discipleship when you have a life and family. Two couples, the Arthurs and the Wasingers, commit together to take seriously God’s discipleship commands, beginning a yearlong experiment. They make small changes in their everyday lives at the rate of one per month, starting with covenant friendship and moving into efforts toward comprehensive social transformation. Sarah and Erin write about the results.

The Arthurs and Wasingers don’t try to change everything about their lives; their aim is to make themselves “a little less ‘normal,’ a lot more vulnerable, way more honest, and . . . a bit more like Jesus.” Their 12 changes are inspired by the 12 marks of New Monasticism, but they are more bite-sized—although still challenging. The two families create budgets to discuss with each other around the question “how can I be more generous?” They decide not to look at Facebook for one day each week. They pray the Lord’s Prayer with their children once a week at bedtime. Such practices won’t change the world. But they will bring people closer to Jesus.